Since 1973, Historic Preservation Month has been observed during the month of May. Preservation Month highlights the importance of saving our built environment and celebrates the role preservation plays in local economies and the continuation of cultural heritage.

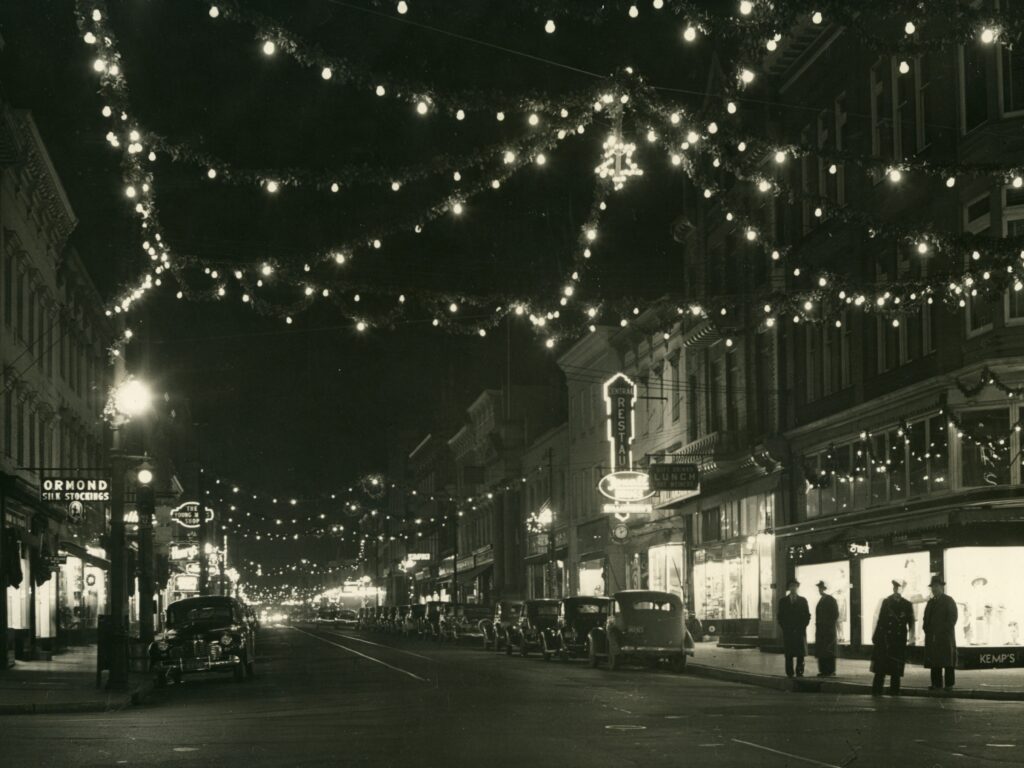

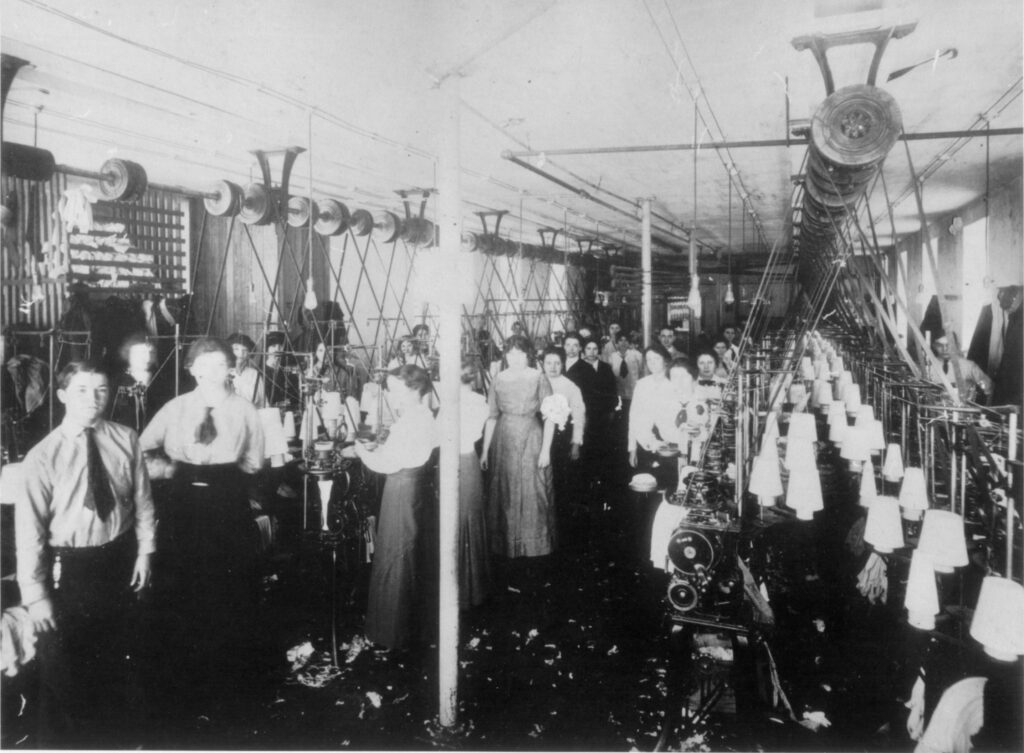

One of Frederick’s early preservation activists was Marshall Lingan Etchison (1894-1960). Marshall came of age in a Frederick that saw rapid growth and change as a result of industrial innovation. With the development of new technology, Frederick’s industrialists established dairies, canneries, garment factories, and other manufacturing enterprises, which fueled the growth of Frederick beyond its eighteenth century boundaries. This economic activity also encouraged the “modernization” of the city’s downtown commercial district.

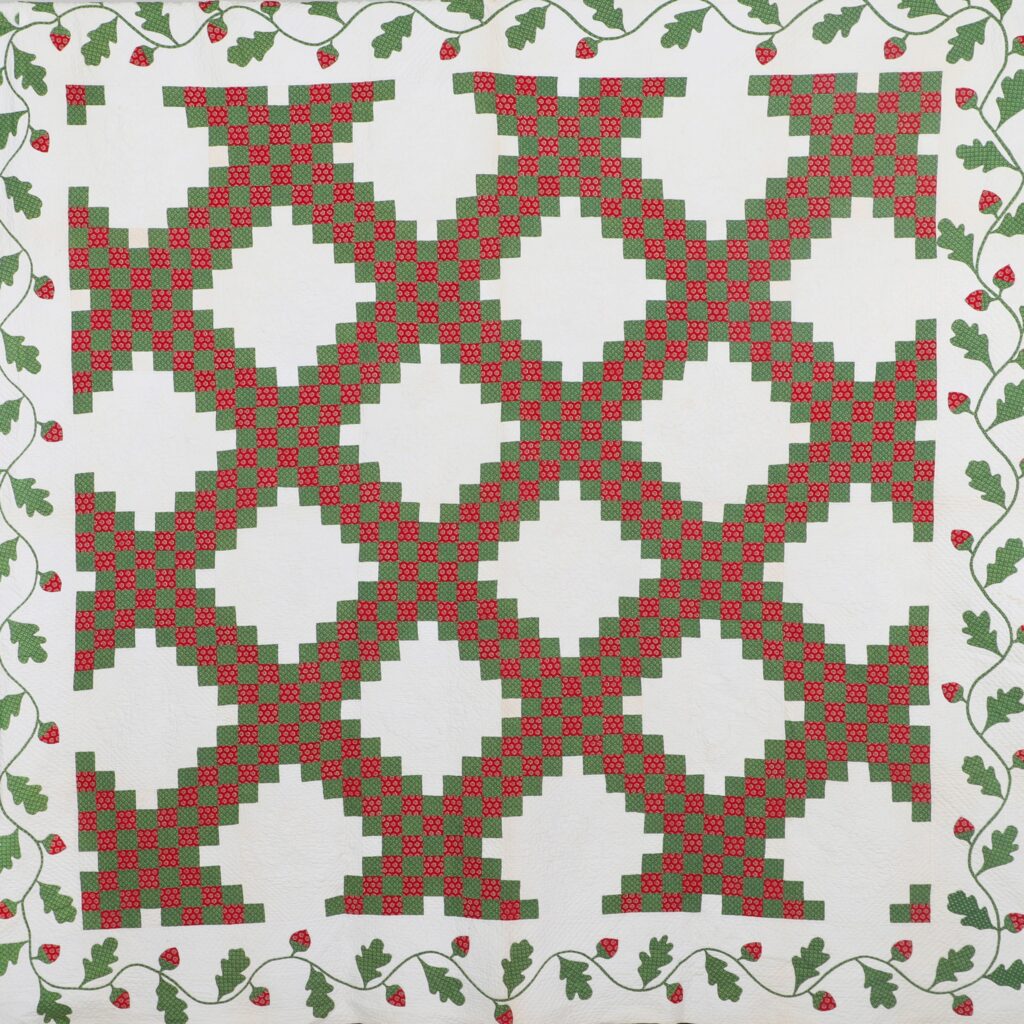

Etchison was a lifelong student of history and an avid researcher and collector. He appraised local estates and led the Historical Society of Frederick County (now Heritage Frederick) to curate a collection of local artifacts and archives. In 1945, in the midst of Frederick’s bicentennial celebration, the Historical Society opened its first museum in the restored Steiner House under Marshall’s leadership. After his death in 1960, he directed his family to donate much of his own collection of Frederick County material culture and his personal papers to the Historical Society.

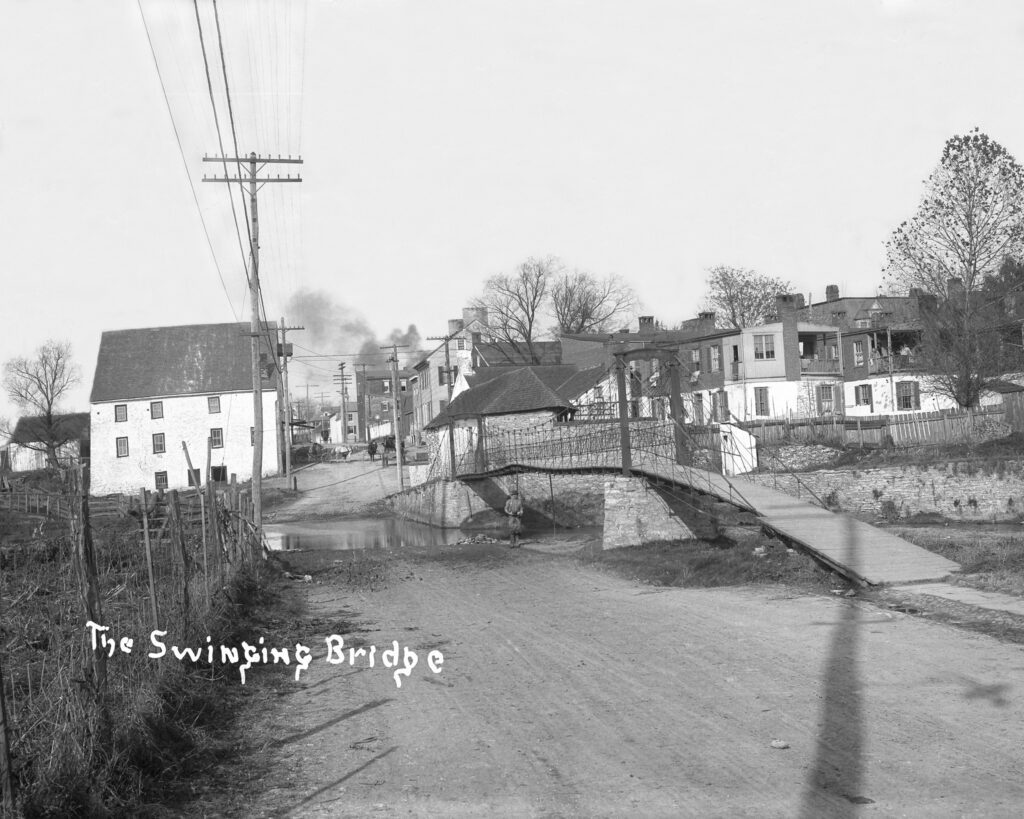

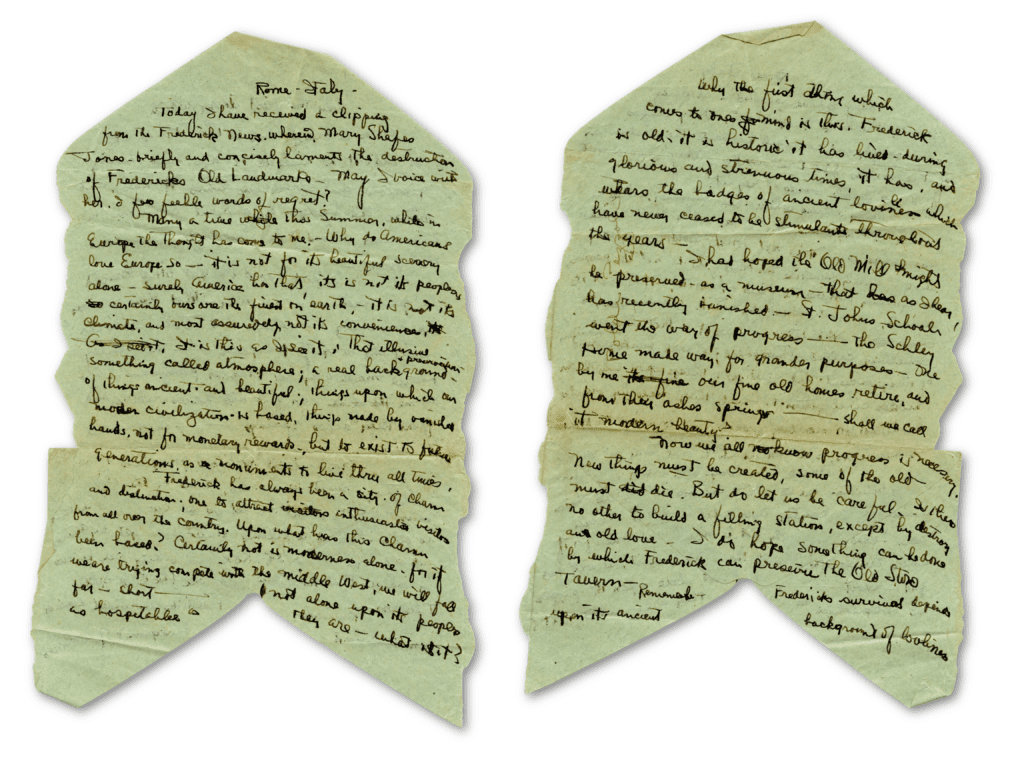

Among these papers now preserved in Heritage Frederick’s archives are hand-written drafts of letters and editorials Marshall wrote in support of preserving Frederick’s historic architecture. In 1926 as the city pressed forward with the demolition of the historic Zentz Mill to clear the way for the development of Baker Park, Marshall wrote an impassioned plea to consider what the city was jeopardizing in its continued destruction of local landmarks.

Written while he was traveling in Italy, Marshall commented that saving old buildings was imperative to maintaining “that elusive thing called atmosphere; a real background and preservation of things ancient and beautiful: things that have real meaning and upon which our modern civilization is based; things made by vanished hands not for monetary reward, but to exist through future generations, as a monument through all times.”

The editorial notes several local landmarks that had been destroyed besides the mill, including the original Saint John’s Literary Institution building on East Second Street and the Old Stone Tavern on West Patrick Street. Interestingly, some of the fabric of the old tavern was repurposed for the reconstruction of the Barbara Fritchie House, including portions of its stairway and floors.

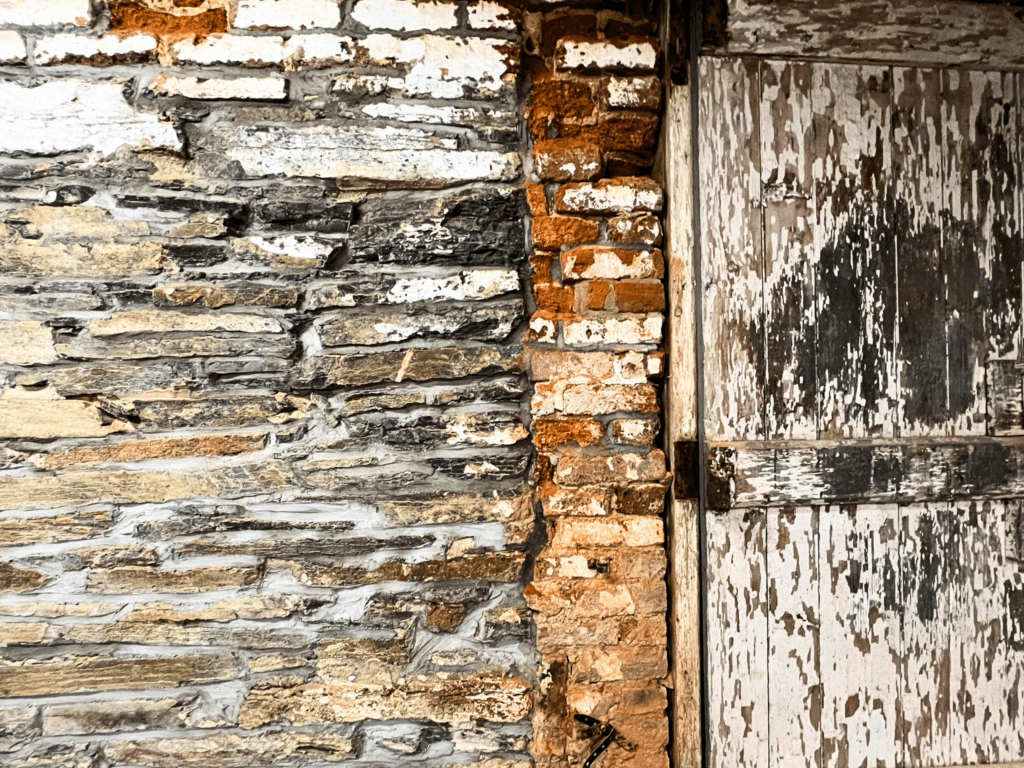

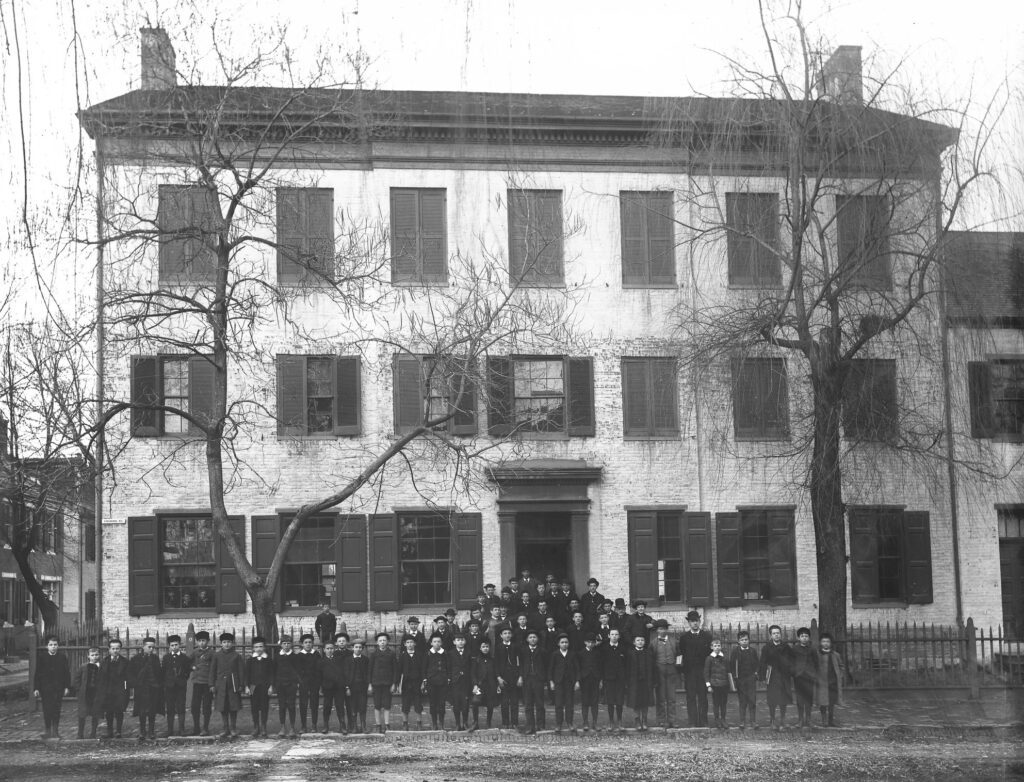

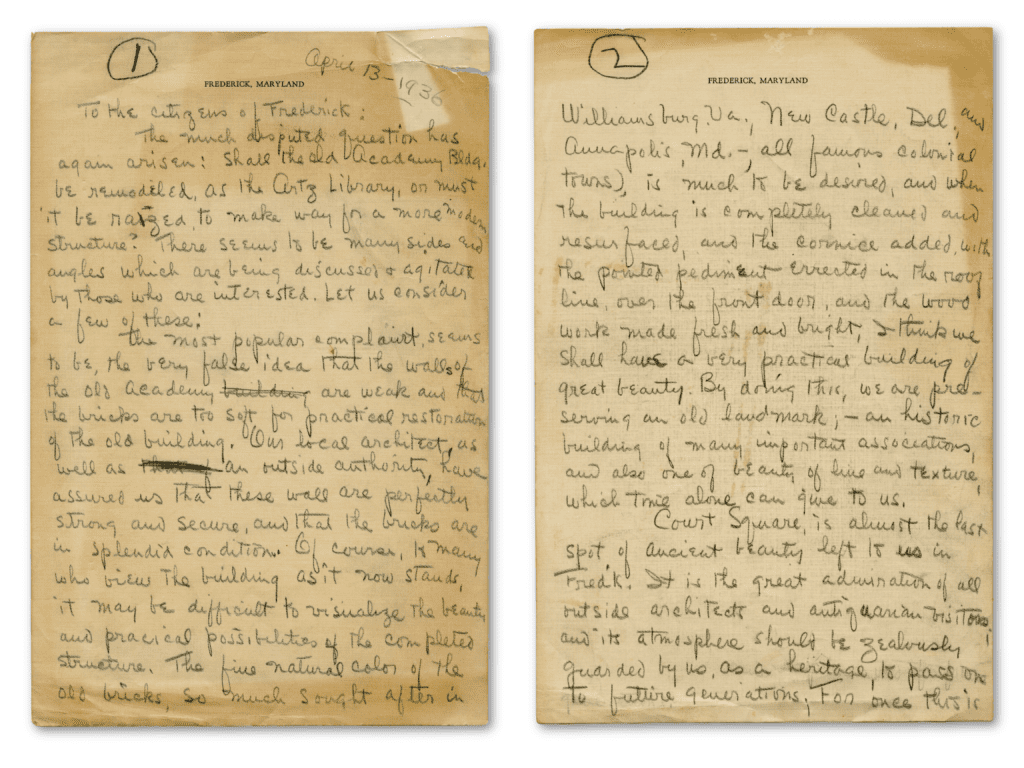

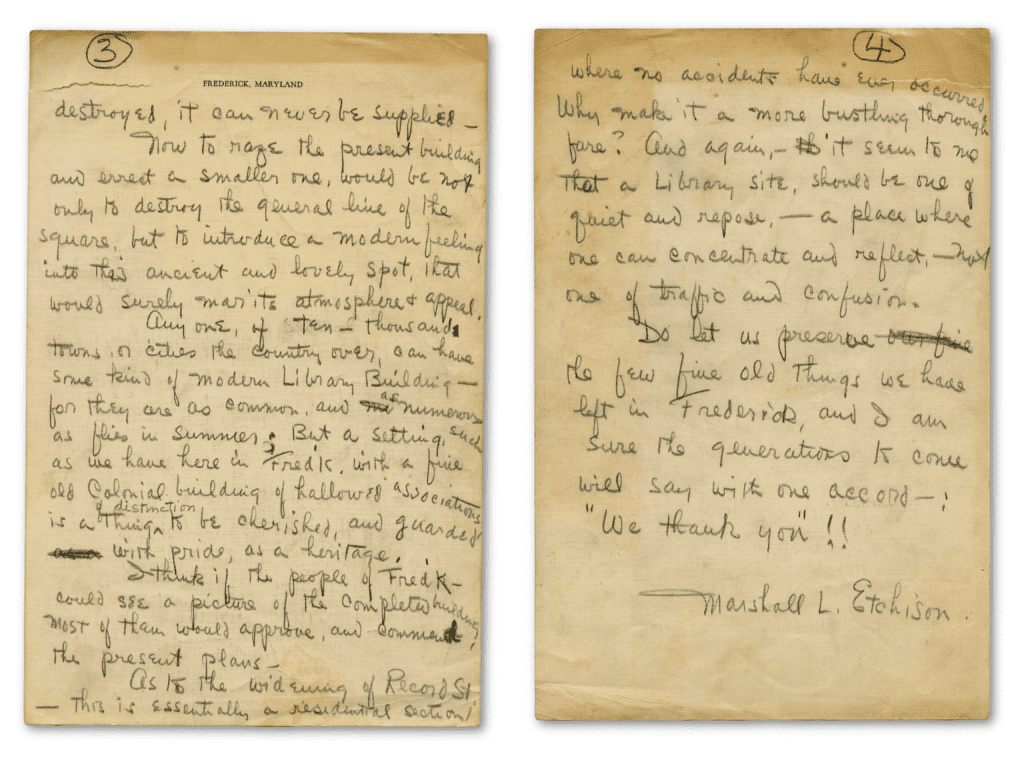

A decade after his pleas for Frederick to balance its modernization with the preservation of its past, Marshall Etchison again committed his feelings to paper when plans for construction of the C. Burr Artz Library called for the demolition of the Frederick Academy. Built in the 1790s, the Academy was a three-story brick building that stood on the corner of Council and Record Streets facing the Court Square. While initial plans for the library project entailed saving part of the Academy, it was eventually demolished to make way for an entirely new structure.

Marshall countered the argument that the building was too old and deteriorated to be remodeled for the purposes of the new library, instead suggesting that the historical nature of the Academy would be an asset to this new public institution for learning. Moreover, Marshall suggested that preservation efforts should focus on saving Frederick’s Court Square, of which the Academy was an essential part.

“Court Square is almost the last spot of ancient beauty left to us in Frederick. It is the great admiration of all outside architects and antiquarian visitors and its atmosphere should be zealously guarded by us, as a heritage to pass on to future generations.” Interestingly, Marshall contextualized his thoughts in the contemporaneous efforts to preserve places with significant links to the United States’ colonial past such as Williamsburg, Virginia; Annapolis, Maryland; and New Castle, Delaware.

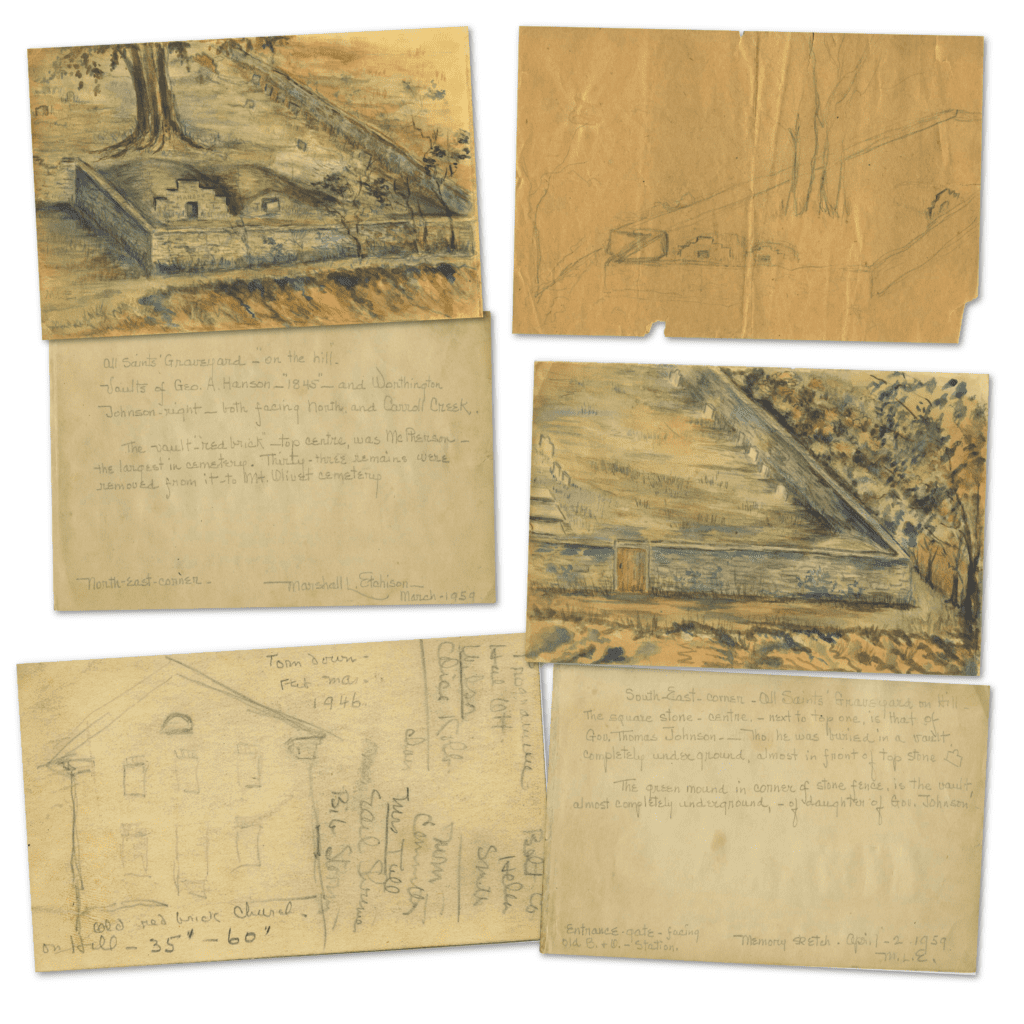

Apart from speaking out on the matter, Marshall Etchison committed his time and attention to documenting historic sites that were disappearing around him. Among his papers are sketches he made of the landscape and structures on the site of the old All Saints Episcopal Graveyard and the original Asbury United Methodist Church on East All Saints Street. His sketches include depictions of grave vaults that remained intact on the site as well as notes about people interred in the graveyard. He also sketched the “Old Hill Church,” the early-nineteenth century brick building where Asbury United Methodist Church was founded and worshiped until their present church on West All Saints Street was completed in 1921.

Near the end of his life, Marshall’s knowledge and belief in the importance of preserving Frederick’s history was sought out by a local committee formed in 1952 to begin documenting the surviving historic architecture in the city. This committee surveyed 976 structures in the city. The work of this committee continued after Marshall’s death in 1960 and laid the groundwork for the creation of Frederick’s historic district, which was established in 1968.

May 3, 2024 By Jody Brumage, Heritage Frederick Archivist