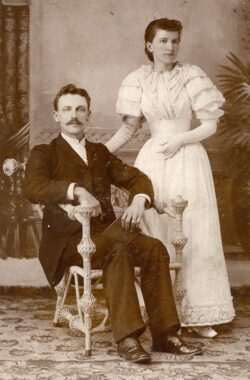

The Tercentenary History of Maryland, published in 1925, announced “If any one man was to be singled out and given the credit for the development of the city of Frederick and Frederick County in the two decades of the twentieth century, that man would be Emory L. Coblentz.” Between 1898 and 1931, Coblentz envisioned, led, supported, advised, and financed innumerable aspects of the community’s growth and change, commerce and services, infrastructure and charity. He was esteemed, admired, appreciated, and honored in business, politics, law, religion, and charitable causes. Then, he disappeared in history.

Joseph D. Baker was Coblentz’s contemporary, although 15 years older. He was a competitor in business and highly regarded as a civic leader, and he invested significant sums in charities that improved the quality of life in Frederick. He was regarded as “Frederick’s First Citizen,” and Baker Park was named in his honor. Baker and Coblentz led remarkably similar lives. Both men were very religious and devoted church-goers. Both abstained from alcohol. Both experienced the death of infant children and also became widowers with

young children in their first marriages. Baker and Coblentz achieved extraordinary success in business and frequently turned those personal successes into service for the Frederick community. This exhibit examines and celebrates their achievements and contributions.

Joseph Dill Baker’s parents, Daniel and Ann, lived in Buckeystown and were highly regarded. Daniel operated a successful tannery and owned several properties. He was described in earlier accounts as the town’s leader. Joseph was born there in 1854, attended local schools, then graduated from Western Maryland College after which he joined his father’s business as a salesman.

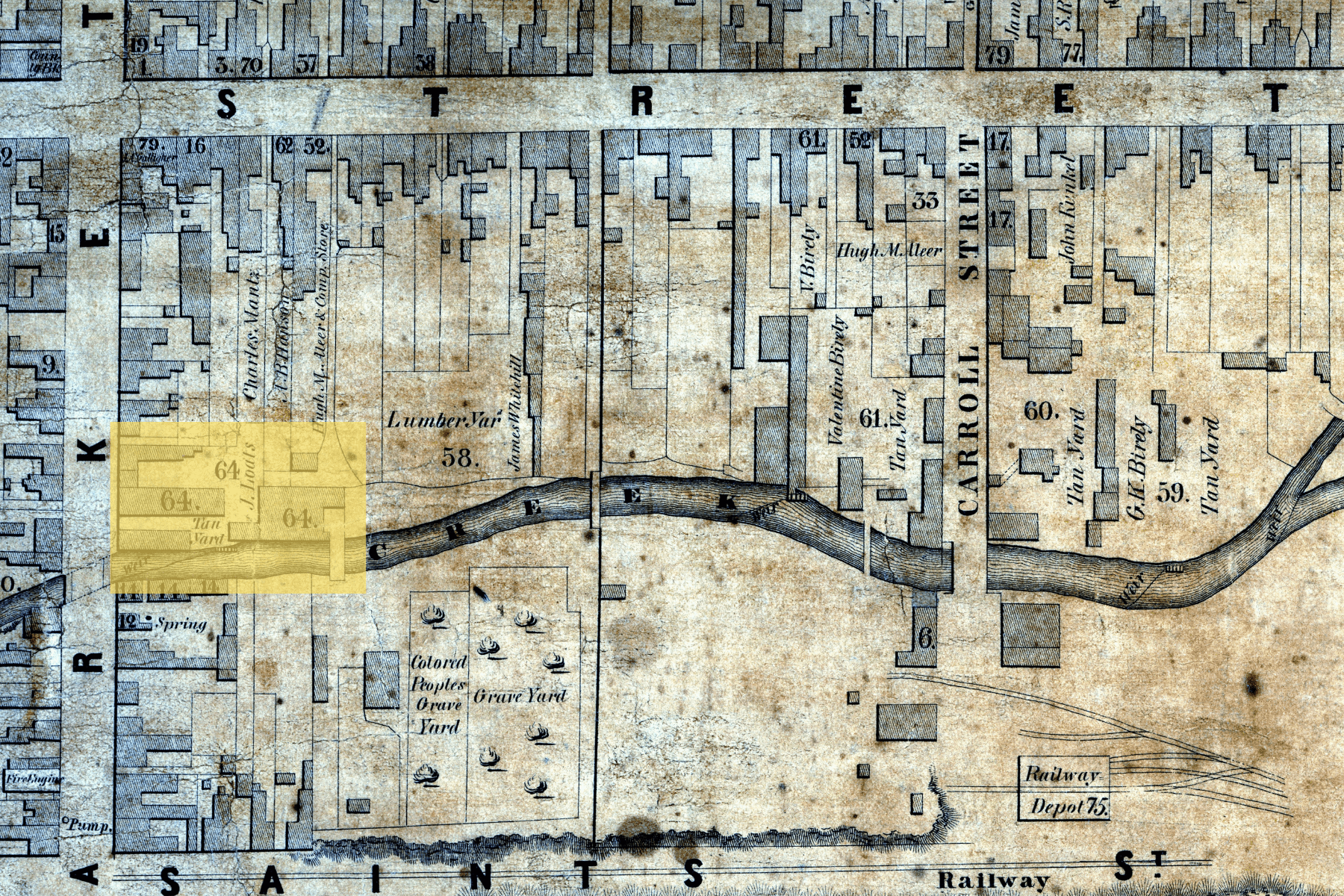

In 1877, at 23 years old, Baker bought a tannery in Frederick owned for 30 years by John Loats, and he continued its successful run for six years before transitioning to his next endeavor: banking.

The Coblentz family in Frederick County started in 1766, when Herman Coblentz immigrated from Germany and began farming in the Middletown Valley. Successive generations of Coblentz farmers followed in his footsteps, managing hundreds of acres, sometimes contiguous to one another, including the preserved expanse lying on the west side of Braddock Mountain, still called Coblentz Farm.

Emory was born on the same farm as his father and grandfather and lived on the farm throughout his youth, even after his parents moved to a house in Middletown. He graduated high school in 1886 and took a job as a store clerk. One year later, when the Valley Savings Bank opened, Emory became its assistant cashier. He stayed with the bank until 1898; after passing the Frederick Bar in January of that year, Coblentz opened a law office. Valley Savings Bank named him its counsel, as did the Frederick & Middletown Railway, and he was on his way.

Baker sold his tanning business in 1883 to start the Montgomery County National Bank in Rockville, MD, which opened July 1, 1884, with Baker serving as president. The bank prospered immediately.

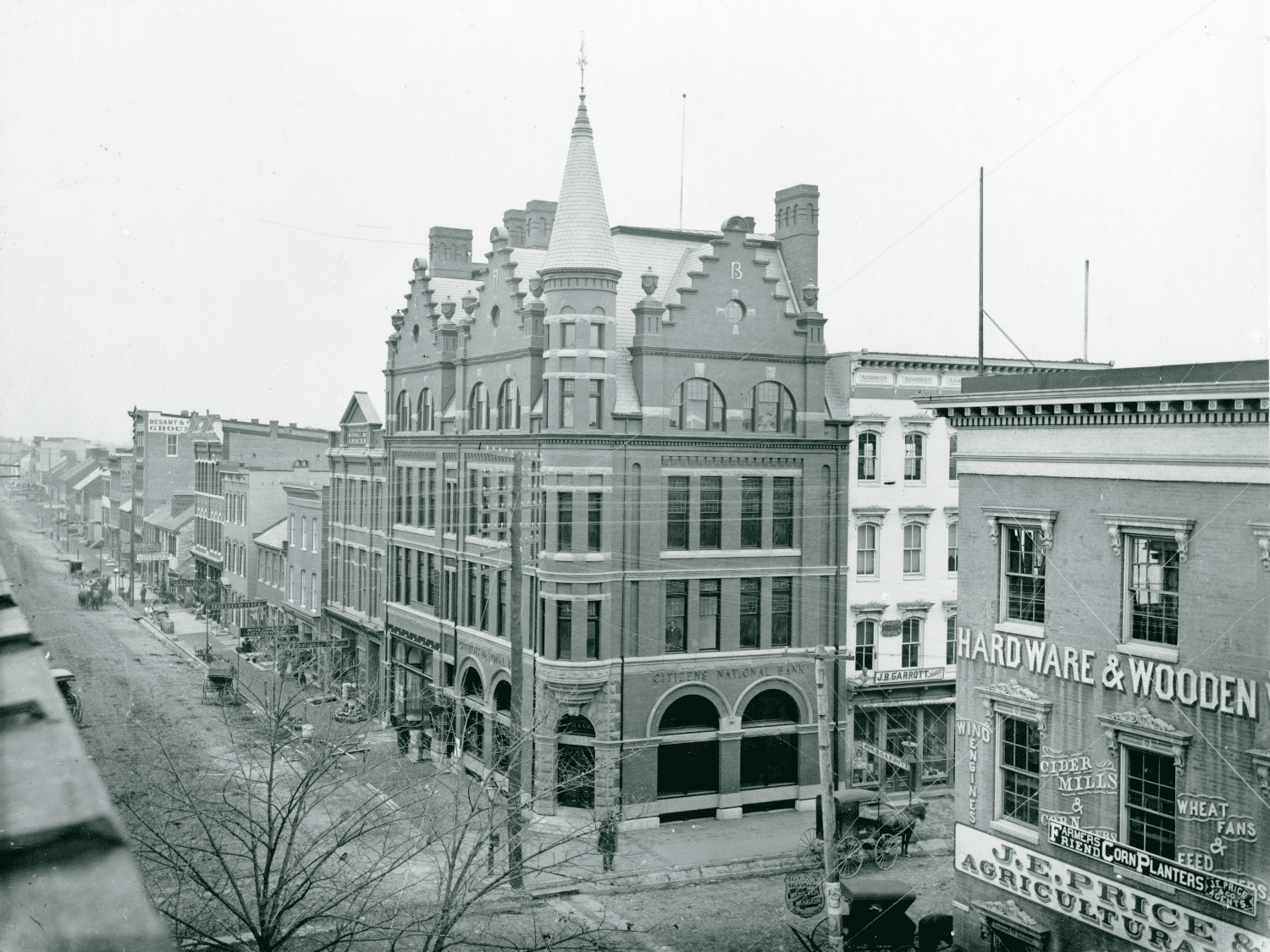

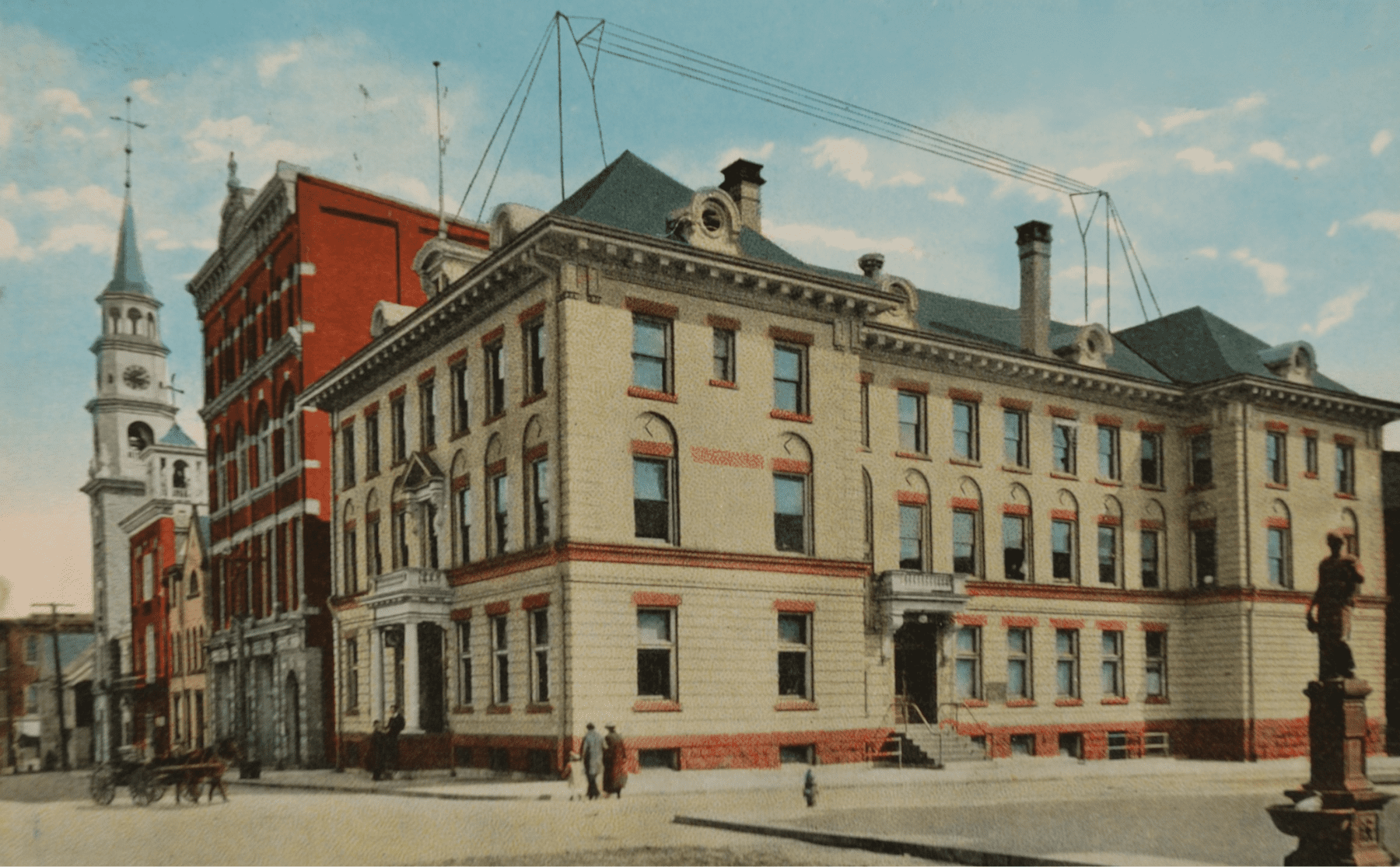

In 1886, he led the organization of Citizens National Bank in Frederick, and he served as president of that enterprise for 35 years. He retired from active management in 1922 but served as chair of the board afterward. Baker organized Peoples National Bank of Leesburg in 1888 and served as president of that institution as well for a few years before giving up the post and concentrating on the Frederick bank.

Two acts by Baker as a financier standout. In 1888, Frederick City attempted to refinance its bonded debt (at that time, more than $500,000) but attracted interest for just 20% of the issue. Baker purchased it all himself then recast the notes for private investors, bond houses, and banks – and sold it all.

After Louis McMurray’s death, also in 1888, his estate held thousands of acres of land in Western Maryland that supported McMurray’s canning business. Baker organized a syndicate of investors who bought the entire estate then re-sold smaller parcels of prime farmland at a significant profit.

For good measure, with his brothers Baker established the Standard Lime and Stone Co in Baltimore with quarries in several locations, which his brother led. For many years, Baker also served as a director of the B&O Railroad.

In his law practice, Coblentz focused on corporate strategy and personal estate administration. By the time he stepped away from active practice with wills and probate matters in 1920, his firm was the largest in the County serving those needs. He remained corporate counsel for several businesses throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

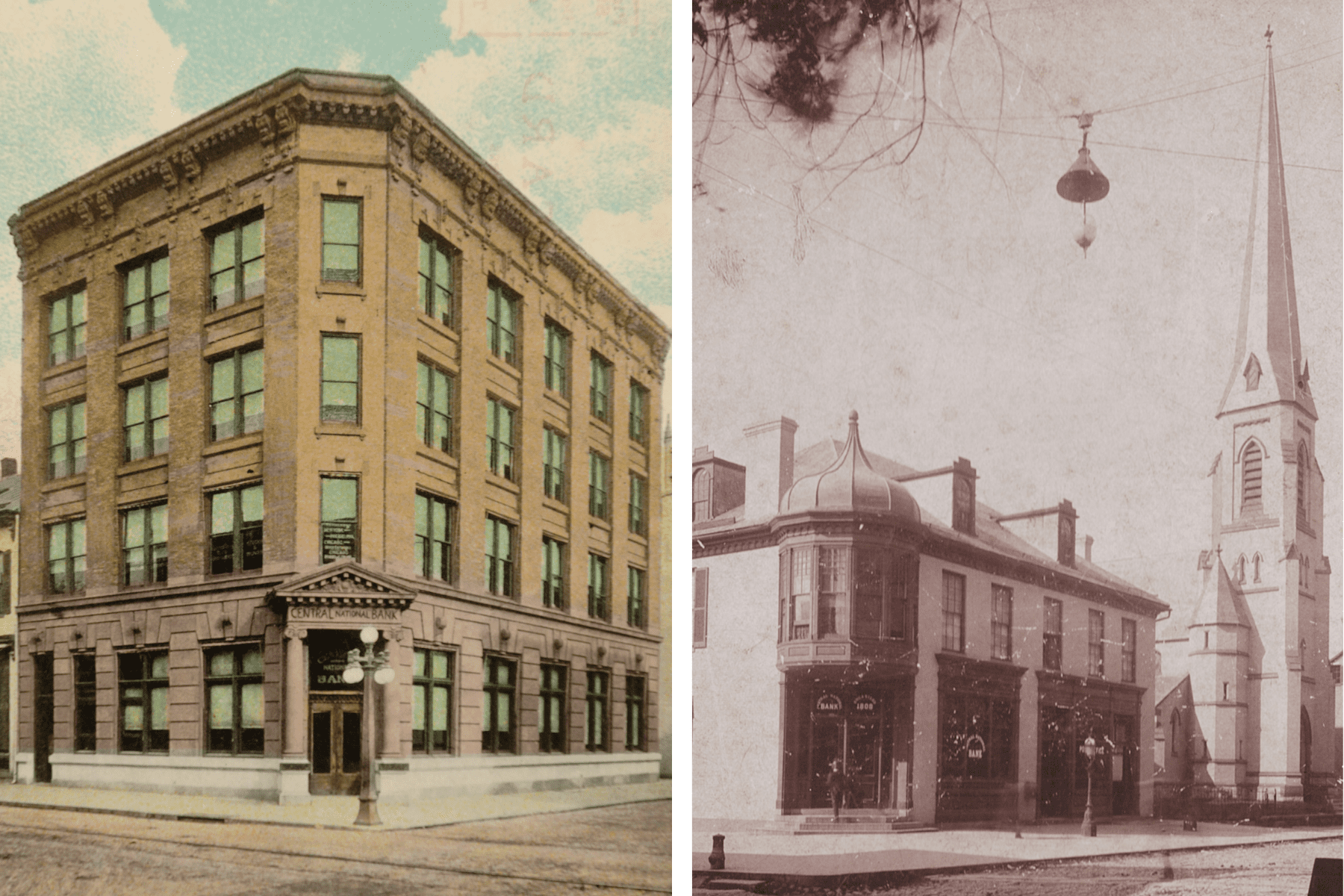

Coblentz was a board member at Central National Bank when its president resigned in 1908 to work for Joseph Baker at Citizens National – the Central Bank board named Coblentz president. In 1913 the bank transitioned into Central Trust. Under Coblentz’s leadership, it became the largest bank (by deposits) in the County.

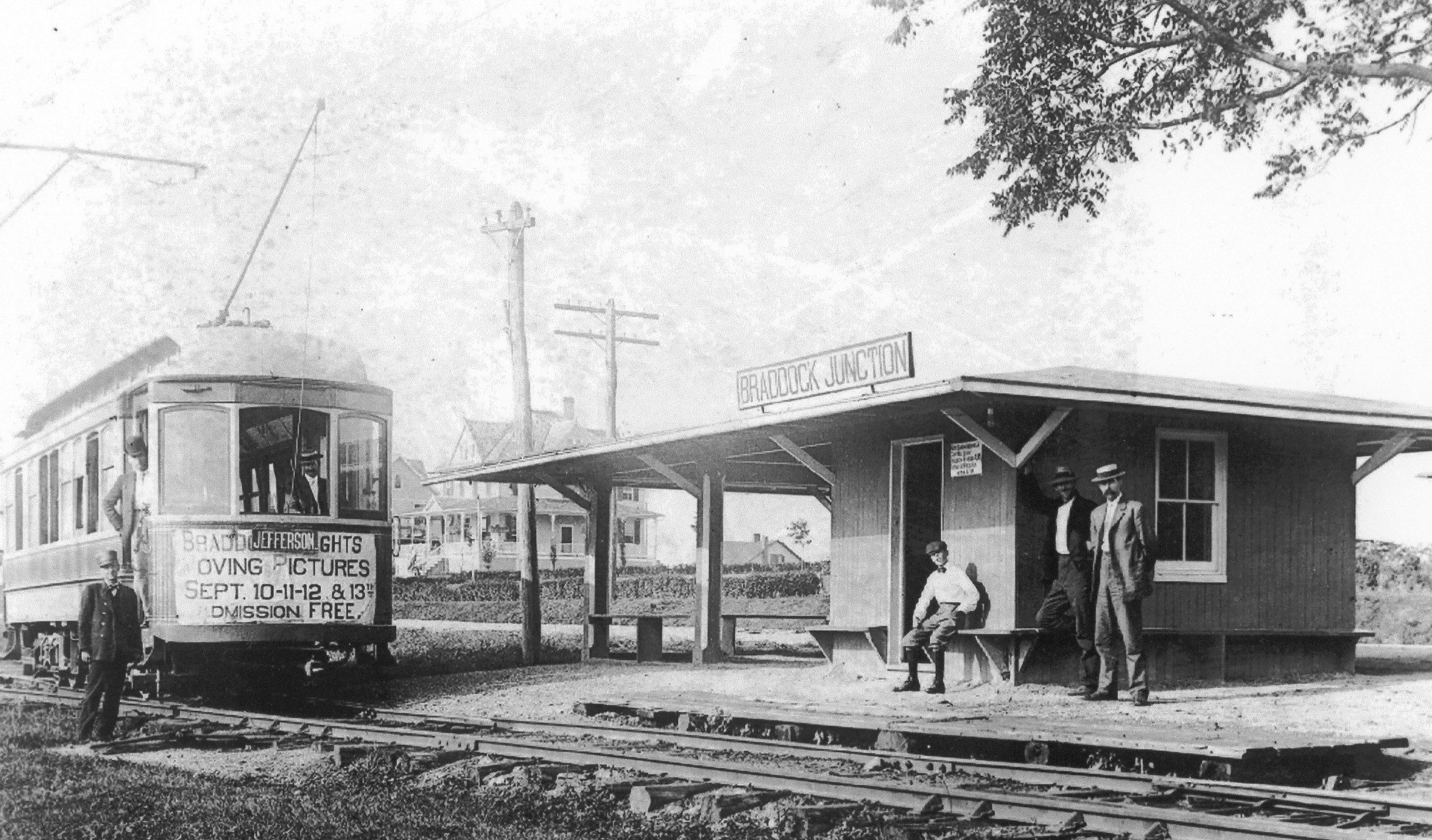

Coblentz served as counsel to Frederick & Middletown Railway for 10 years, and then became its president, also in 1908.

In his unpublished autobiography, Coblentz explained that he created Peoples Fire Insurance Company because he believed an acquaintance was mistreated in another situation and wanted to give him a better opportunity. He became president of the new business in 1908 and ran the company profitably for more than 20 years.

But, Coblentz’s genius for business strategy and management is reflected in his greatest achievement: consolidating several local trolley companies into the Hagerstown & Frederick Railway, which generated its own electric power, then transforming the railroad into the largest electric utility in Western Maryland: Potomac Edison. He served as chairman of the board between 1923 and 1932 and then as an executive board member until his death.

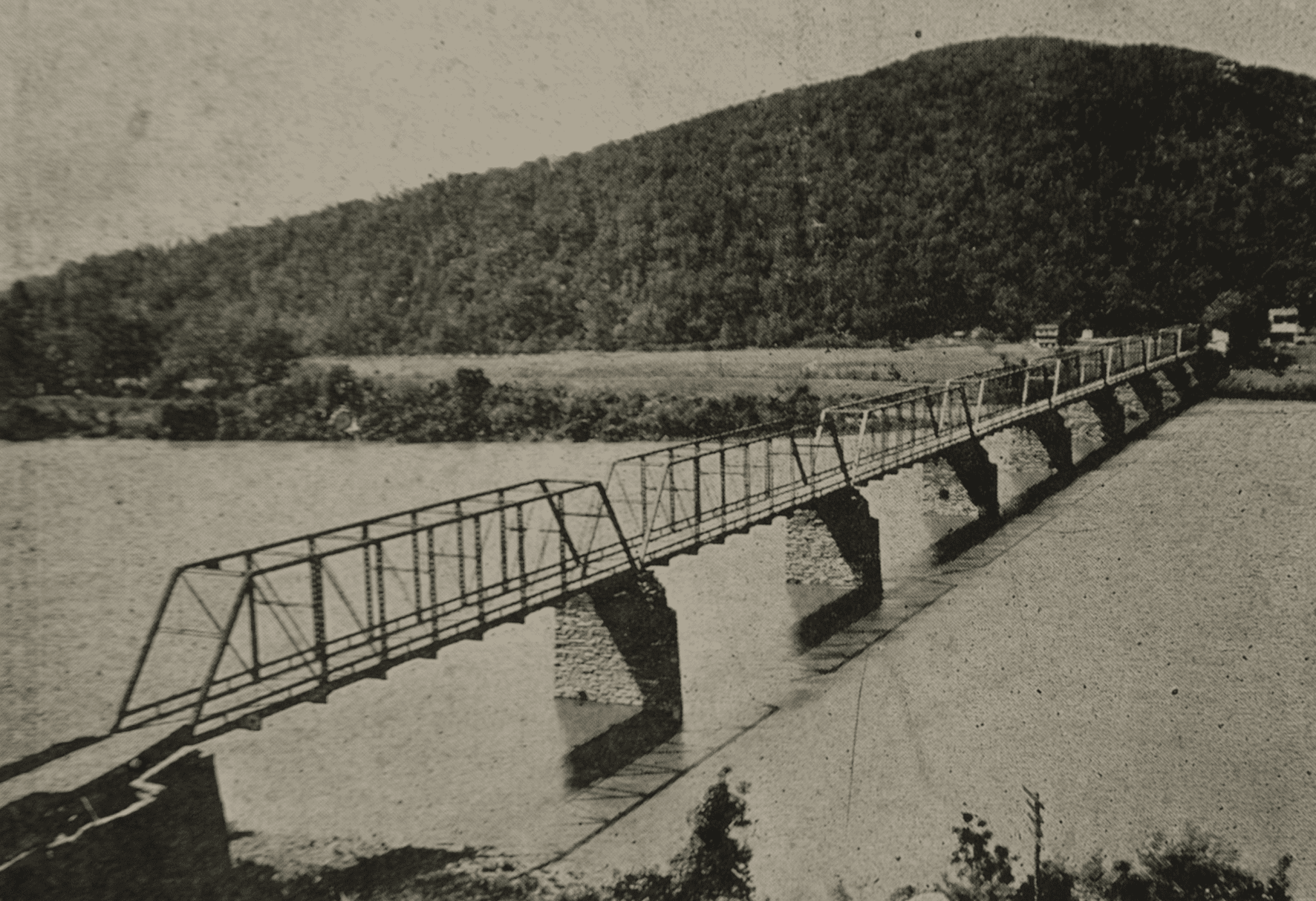

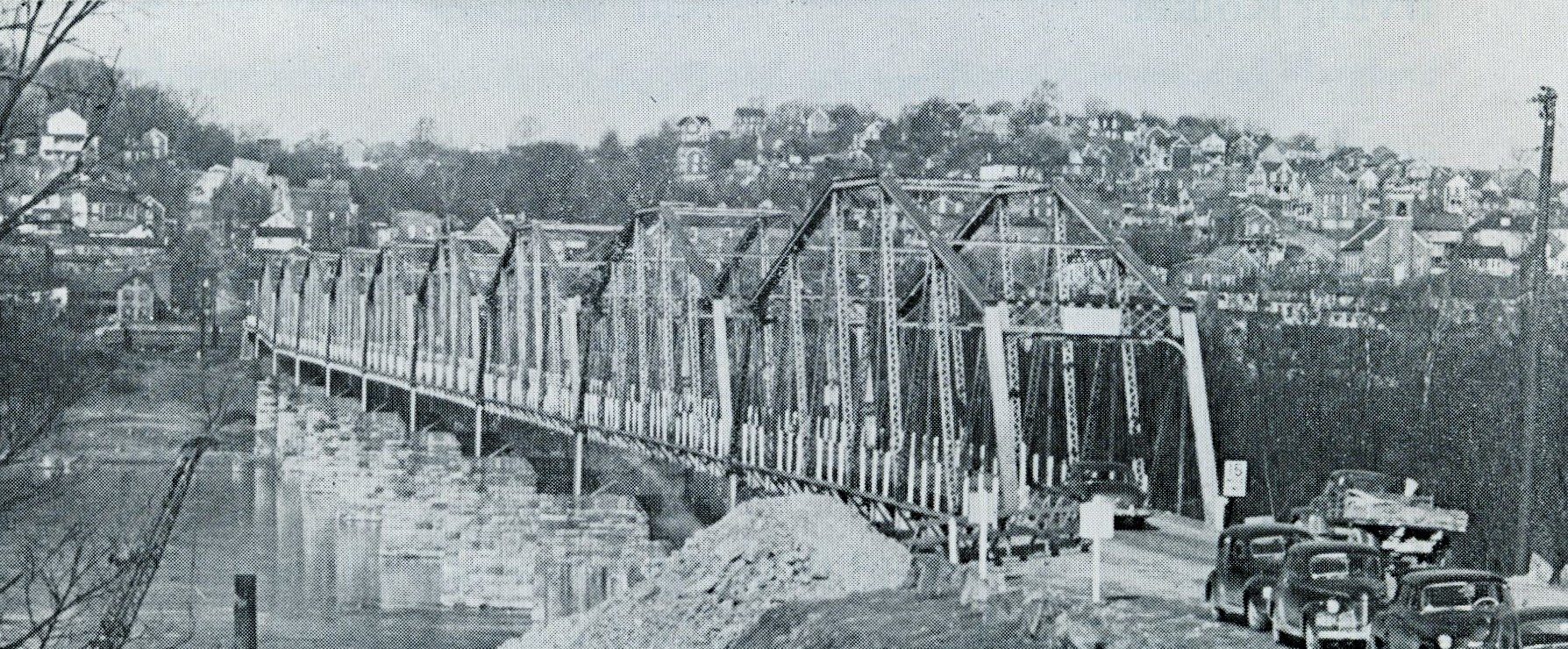

In June 1861, Confederate soldiers burned the bridge over the Potomac River that linked Berlin (now Brunswick), MD, to Lovettsville, VA. As a result, for more than 25 years the two closest bridges to Frederick were in Georgetown and Harper’s Ferry (a ferry service from Lovettsville did operate during this period). In 1889, Baker led a company that built a bridge at Point of Rocks in Frederick County.

In 1893, he led the effort to build a second bridge, this time at Brunswick. Both started as toll facilities but eventually became government resources. The bridges immediately expedited local travel between the states and offered access from Loudoun County to the B&O Railroad in Frederick County as well as markets in Frederick, Baltimore, Hagerstown, and beyond. The improvements also linked travelers coming north out of Virginia to the east-west crossroads in Frederick.

At the same time Baker was buying lots that would become Mullinix Park, he invested in a building project on adjacent property for improved housing for the City’s Black community. In 1928 Frederick City donated land at All Saints and Bentz Streets for the project and Baker paid for the construction of what became the Culler Apartments.

An obvious infrastructure improvement led by Emory Coblentz changed the local economy: the consolidated trolley network he created made transportation and freight patterns dramatically better and easier.

Farmers, employees, students, shoppers, and day-trippers all had a cheap, efficient, systemic way to travel and ship in Western Maryland, particularly its towns and cities. Many manufacturers had side tracks installed directly onto their properties to expedite shipping and receiving.

Similarly, Potomac Edison created a distribution system that brought electricity into businesses and homes across the region, which transformed commercial enterprise and a way of life.

First as counsel then as the president of the trolley company, Coblentz also oversaw the development of the Braddock Heights amusement park, which the trolley company created as an attraction to sell trolley tickets. Coblentz and other investors later created the Braddock Heights Development Corporation as well as the Braddock Heights Water Company. The former opened the Jefferson Boulevard extension to new residential construction while the latter built a permanent water supply system to serve the community.

Baker was a visible and enthusiastic supporter of, and anchor donor to, the effort to build Frederick City’s original YMCA building [It was the first insurance policy issued by Coblentz’s Peoples Fire Insurance Company in 1908].

During the 1910s into the 1920s, Frederick City leaders bought lots adjacent to and west of Bentz Street with a goal of creating a park. In 1926, Joseph Baker offered to donate the cost of two properties to the City if it would include them in the park. City leaders dedicated the park in June 1927 and two months later voted to name it Baker Park to honor Baker’s outstanding interest in the welfare and progress of the City.

Leaders in Frederick’s Black community had advocated for a park as early as 1903. When Baker Park opened, it was segregated. In 1928, Baker donated land for the effort that created Mullinix Park to serve Frederick’s Black community. It opened in June 1929; the pool at Mullinix Park bears the name of William Diggs, a Black man who worked as Baker’s valet and chauffeur for 50 years.

In 1929, Baker donated $100,000 to Frederick Hospital so that it would add treatment and convalescent facilities to serve Frederick’s Black community, which initially was called the Baker Wing.

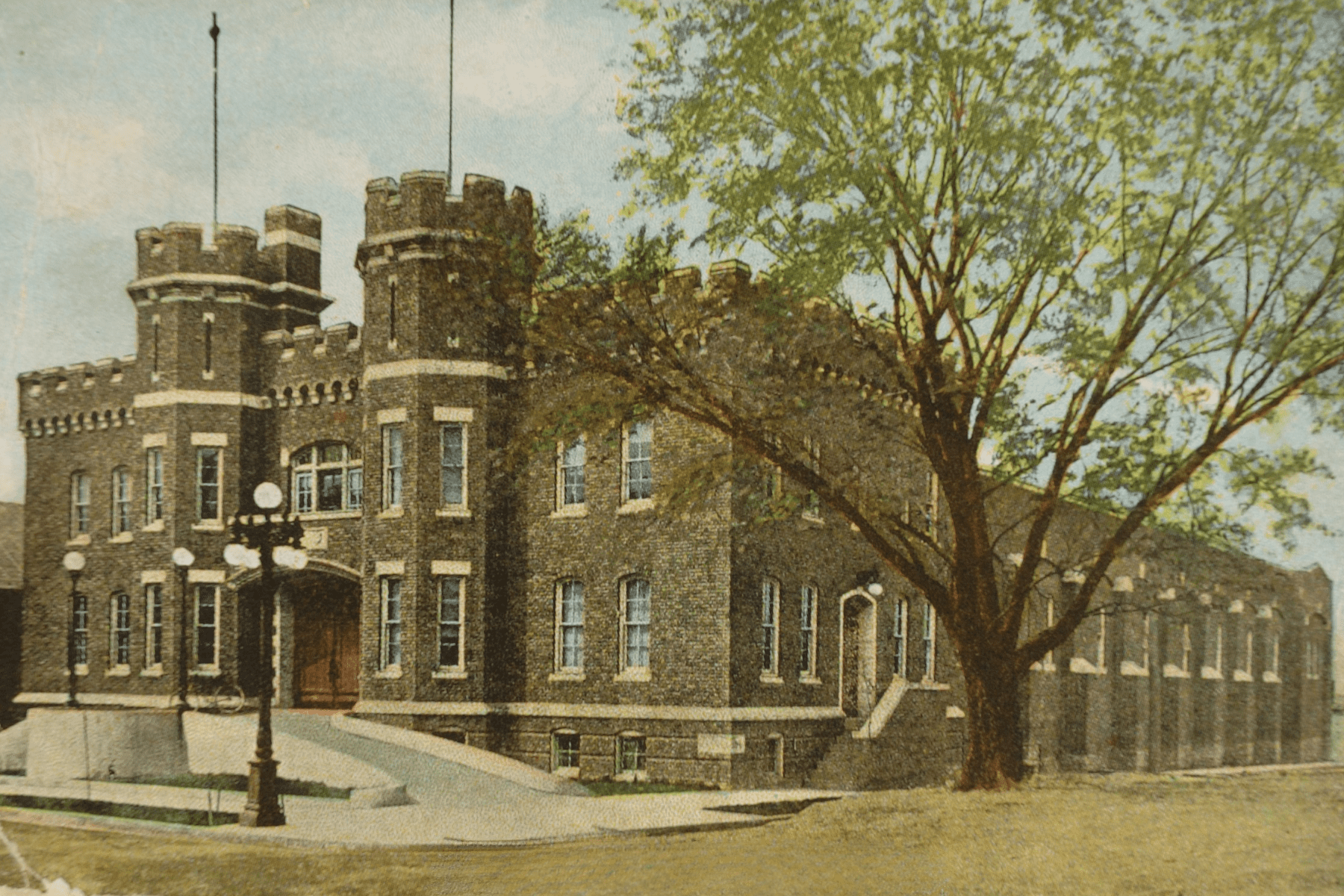

Coblentz served on the committee that led the effort to build the National Guard Armory at Bentz and 2nd Streets in 1915 when nothing existed in that part of Frederick City.

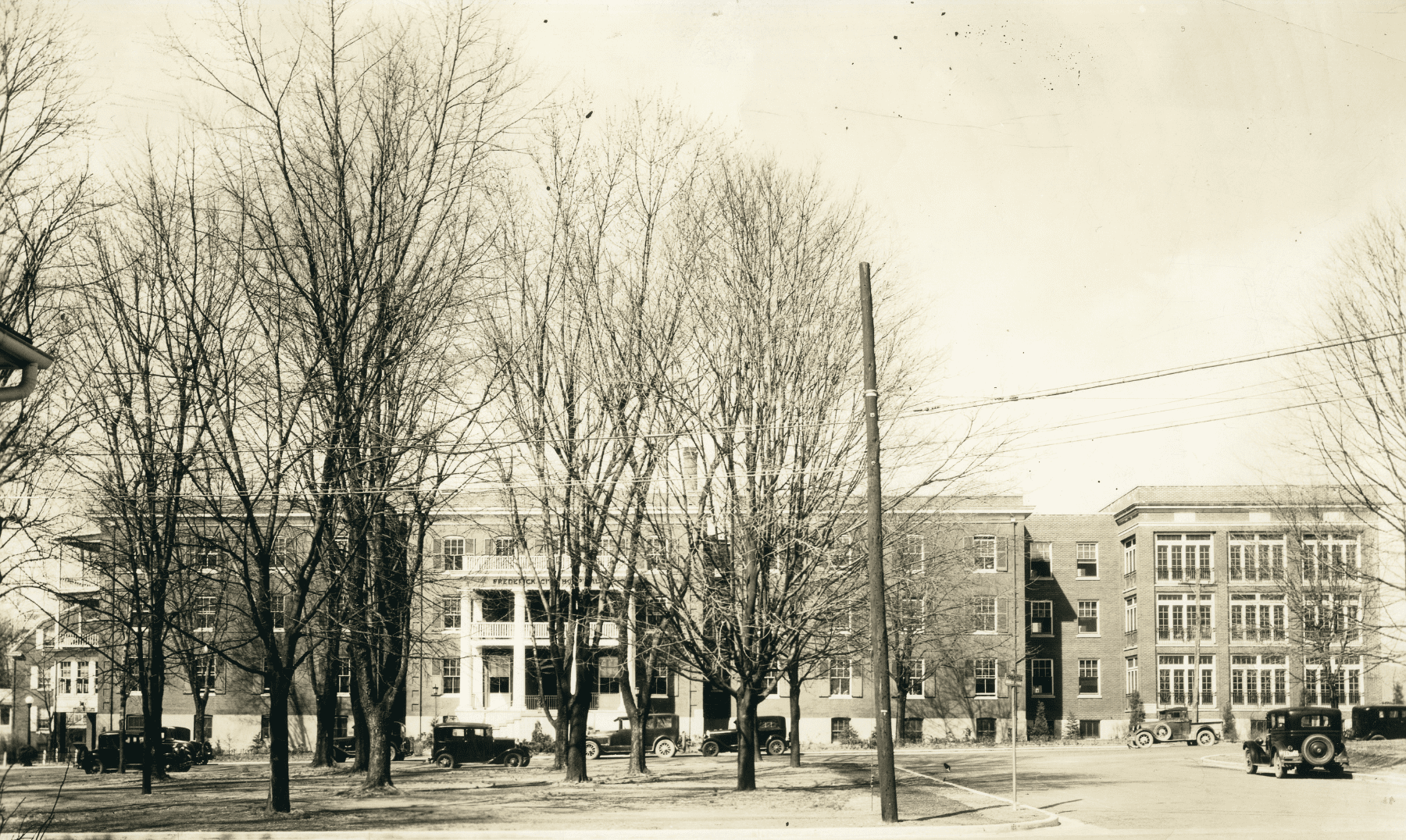

Between 1921 and 1931, Coblentz served as chairman of the Frederick Hotel Company, a civic holding corporation that raised investment capital for, built, then owned the Francis Scott Key Hotel; it leased management control to a partner to operate the property. Joseph Baker lived in the hotel during his last years.

In 1923, Coblentz led the movement to erect Memorial Hall in Middletown, and he donated 40% of the funds needed to complete the project.

In 1925, he agreed to lead a fundraising initiative to sustain Frederick Hospital; the effort began in 1928 and attracted $140,000 in donations ($2.5 million in 2024 dollars). Subsequently, Joseph Baker and Charles Shank made additional investments to expand the hospital building plan, and Coblentz then led the Building Committee.

He developed a successful strategy to raise the money necessary to build Memorial Park adjacent to the armory after an earlier effort failed. He also persuaded the Evangelical Reformed Church to move its cemetery, which sat on the land, to another location, which made the park possible there.

Baker supported many charitable causes, large and small. His daughter – many years later – remembered how poor and suffering people would knock on their front door and ask for help; her father wrote down the names and circumstances, and investigated – she presumed he offered help if the stories checked out. His two most prominent philanthropic causes were the Record Street Home and Buckingham Industrial School for Boys.

The Record Street Home opened in 1892 as a home for “respectable” people who had no means to care for themselves in advanced age. Baker donated $50,000 in 1925 and again in 1926 to expand the original facility west to Bentz Street (ultimately, with an unobstructed view of Baker Park).

Baker and his brothers obtained a charter for the Buckingham Industrial School for Boys in 1898. Their intent was to care for, support, and educate poor boys of good character. Parents signed a contract turning over guardianship to the school, which held responsibility until each boy reached 21. Students learned a classic curriculum until 17 then chose a trade in which to apprentice or attended the Baltimore Business School. All of their expenses were paid by the school, which the Bakers funded entirely. The school closed in 1944.

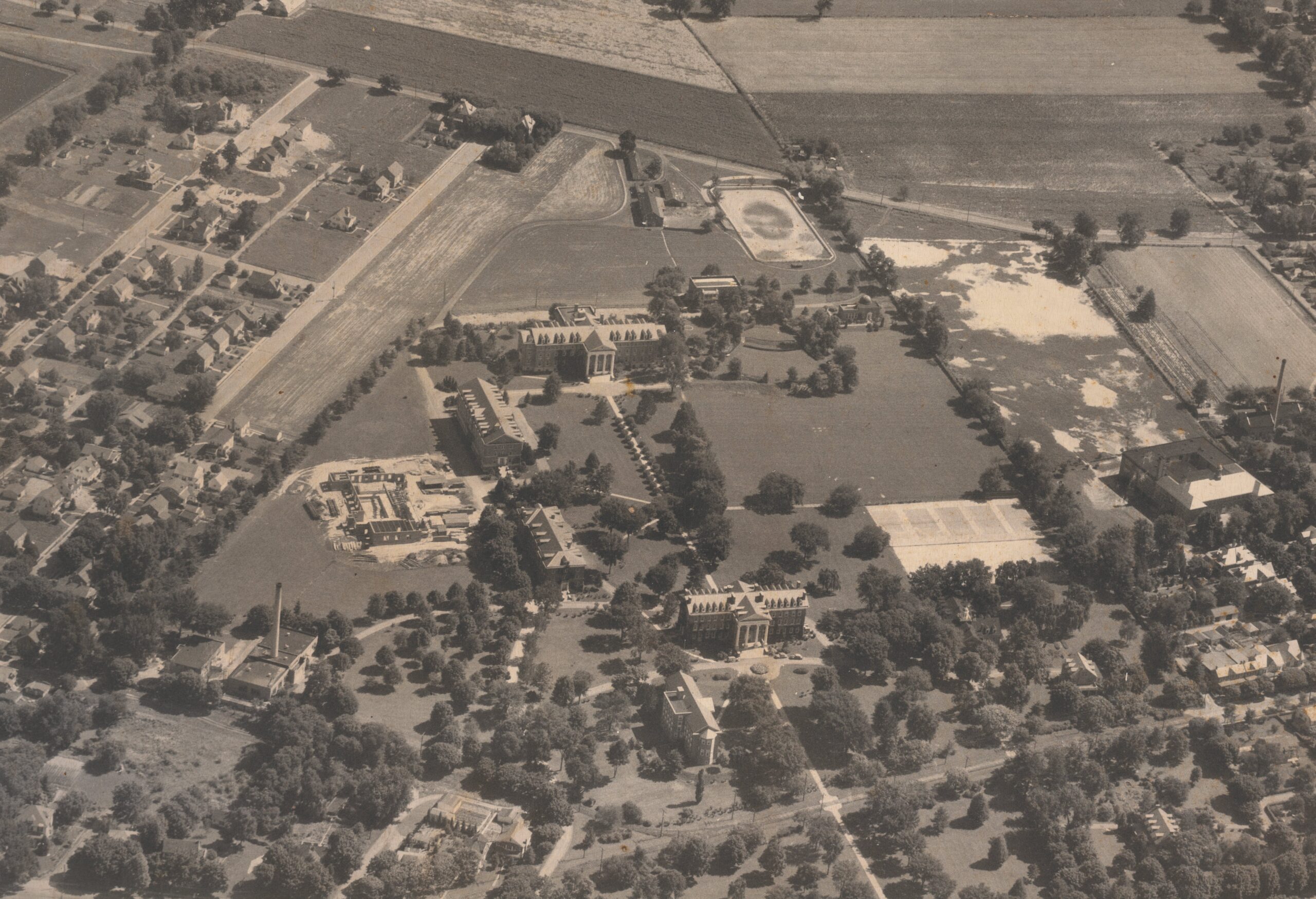

Coblentz served as a trustee at Hood College from 1914 until his death in 1941. He was elected vice chair during the last 10 years of that period and led both the Finance and Building Committees. He also led the effort to replace Dr. Joseph H. Apple – the school’s first president – when Apple announced his retirement in 1933 after 40 years leading the college.

At Hood, Coblentz oversaw the construction of Alumnae Hall, the President’s House, Apple Library, expansion of Brodbeck Hall, Carson Cottage, Hodson Theater, Martz Hall, Meyran Hall, Laboratory School, Shriner Hall, Strawn Cottage, Williams Observatory, and Coblentz Hall, which his fellow trustees voted to name in his honor for his long and distinguished service.

When Coblentz joined the Hood board, the college’s endowment equaled $25,000; when he died, the endowment had increased to $400,000 (1500% increase). He was a prolific donor to the college himself, and saw all six of his daughters graduate from the school.

Coblentz donated liberally to the Reformed Church in Middletown as well as Frederick Hospital and annually to numerous other civic organizations.

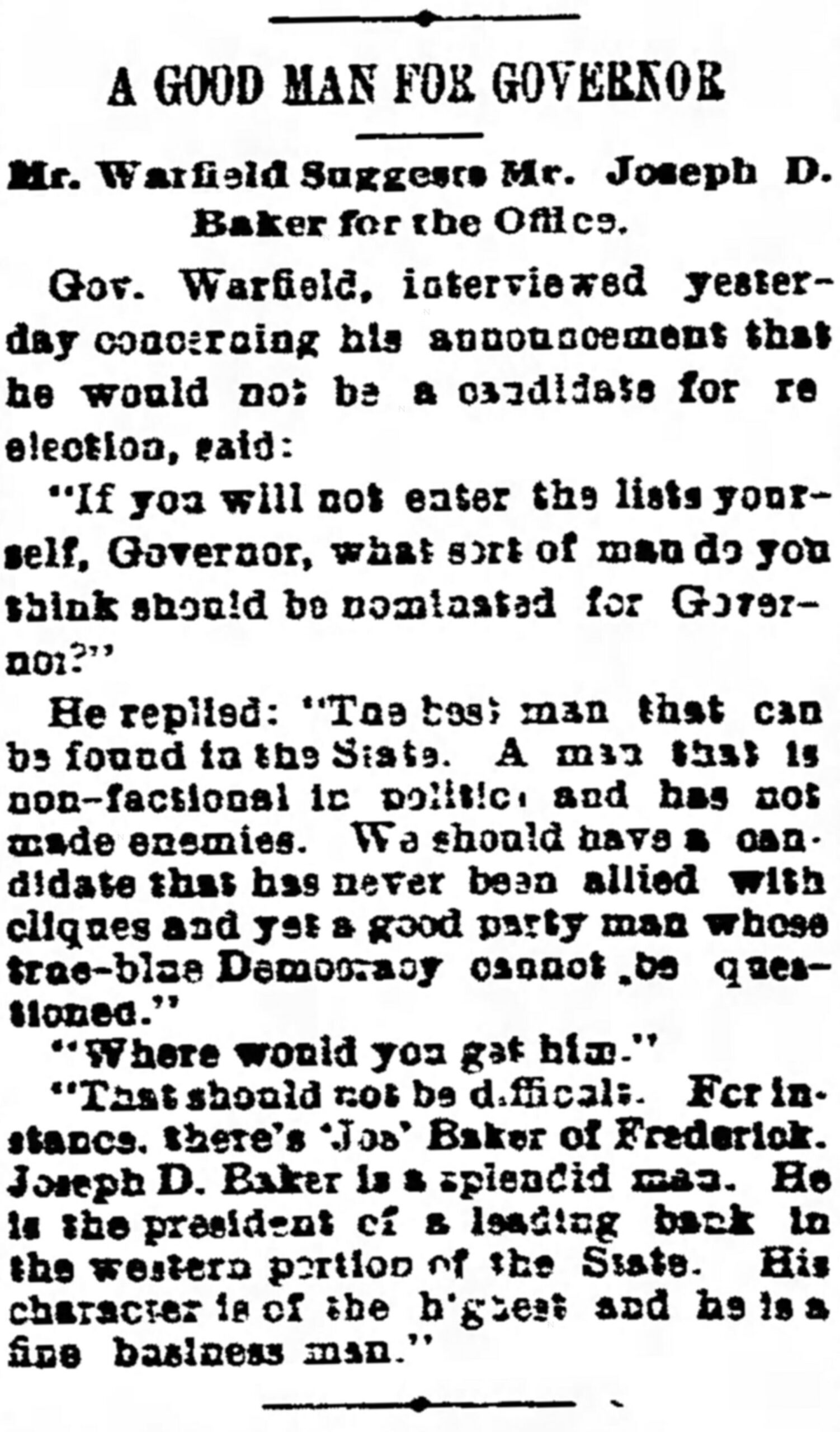

In both Frederick City and Frederick County, Baker held considerable influence in political matters over decades, not least because of his investments but also because he was regarded as both smart and honest. Whatever the objective, his long, public record proved that his focus remained the best interests of the community.

In 1907, support emerged for Baker as a Democratic candidate for governor, locally as well as in Balti-more (where state power brokers operated). Baker, himself, was ambivalent but agreed to have his name advanced despite refusing to campaign.

At that time, the issue of prohibition – or local availability of liquor – figured prominently. Baker abstained from alcohol his entire life, and as his candidacy gained attention he made plain his personal view and said he wouldn’t be a champion for alcohol to win votes. Although his support in Frederick County remained strong it declined among party loyalists, and the nomination eventually went to Austin Crothers, who won the election. If the turn of events bothered Baker, he never said as much publicly. Esteem for him grew for his integrity and willingness to speak forthrightly about a significant and controversial matter.

Baker chaired Frederick County’s Selective Service commission (draft board) in 1917.

Coblentz got involved in politics early and eagerly but not fervently; it enabled him to meet and befriend many people in numerous industries across the County and State.

In 1912, Governor Goldsborough, a Republican, appointed Coblentz, a Democrat, to the Board of State Aid and Charities, on which he served for four years. In 1919, he won election as a state delegate. As a successful lawyer and businessman who was highly regarded around the State, he was more than a political novice; the Maryland House named Coblentz floor leader and chair of the Ways and Means Committee.

In 1930, Coblentz won election to the State Senate, defeating Edward Delaplaine, who later became an esteemed judge in Frederick. But, his only term yielded little in the way of notable change or success because of problems that arose in 1931.

He did vote against legislation in 1933 that made alcohol legal and available throughout Maryland after a vote by other states repealed Prohibition; the faction in favor prevailed, however.

When the Great Depression began in the United States in 1929, Joseph Baker was 75 years old and retired from active management of Citizens National Bank. Baker’s son, Holmes, served as president of the bank then, and it survived the economic turmoil.

Joseph Baker had spent his adult life in public view, as a businessman, political advisor, and philanthropist. For his 80th birthday in 1934, 282 people, including Maryland’s Governor Ritchie (and Emory Coblentz), met for a celebratory dinner at the Francis Scott Key Hotel. When he died in 1938, local newspapers lauded him as “Frederick’s First Citizen.” Many of his investments in the City’s quality of life continue to serve the community today, including the hospital, Record Street Home, Baker Park, and Mullinix Park.

In 1929, Emory Coblentz was chair of the board at Potomac Edison, still president of Central Trust, still president of Peoples Fire Insurance, active as a director or legal counsel for numerous local businesses, and about to be elected state senator. He would turn 60 years old in November and was at the apex of his business and professional life. By his own accounting, he had a net worth of approximately $30,000,000 (in 2025 dollars). However, as the nation’s economic catastrophe engulfed banks across the country, Coblentz invested his own resources into Central Trust with the hope of saving the bank and the savings of his customers – but it didn’t help. Central Trust closed September 3, 1931, and Coblentz spent the next five years in constant court battles to prove himself innocent of fraud; he ultimately prevailed in every case.

His hand-written diaries during the period make plain the burden that the bank collapse and subsequent litigation caused him emotionally and in the community. After 40 years leading Sunday School and the choir for Reformed Church in Middletown, Coblentz resigned in 1932 to avoid having to engage uncomfortably with his neighbors who blamed him for their financial losses.

The bulk of his cash and securities disappeared with Central Trust, and he voluntarily turned over all his property and remaining investments to the receiver for Central Trust. But, Coblentz continued earning annual compensation as a director at Potomac Edison, as counsel and director for a local manufacturing company, and through a pension from an insurance company he once owned as well. He never returned to that apex, but he also steadfastly refused to pursue bankruptcy. Instead, he spent years re-paying personal obligations, including roughly $1 million (in 2025 dollars) to the lawyers who represented him in all his legal challenges.

By 1941, when cancer claimed Coblentz at 71, his honor and character had been rehabilitated in the eyes of many in Frederick County although not all. A remembrance of him in the Frederick News Post called Coblentz one of the greatest leaders Frederick County ever produced and lamented that focus on the bank failure caused people to overlook or forget his significant contributions and accomplishments.