Super-sleuth Nancy Drew, Creative problem solver Angus MacGyver, Hero Librarian Nancy Pearl—just a few of the real and fictional characters that I, as a museum curator, frequently try to emulate. Recently while knee-deep in a complete inventory of the object collections of Heritage Frederick, I came face-to-face with 7 boxes that I have been trying to avoid for months. They contained the findings from an archaeological excavation that took place on the Heritage Frederick property at 24 East Church Street in 2000.

With the exception of those marked metal, glass and miscellaneous, the majority of the boxes are labeled stoneware, redware and ceramic sherds. While confident that I knew what a shard was, I at first assumed the word was misspelled on the boxes. A quick online search cleared things up, revealing that while a shard is a broken fragment of something, usually glass which typically has sharp edges, a sherd is a broken piece of pottery that was once part of a vessel or container. There are 604 of these individually catalogued items, many smaller than a dime and a few that are fully intact glass bottles. Through the process of inventory, photography and then research, I have come to really appreciate what a unique and marvelous window these items have been able to reveal about Heritage Frederick’s personal history as the fifth occupant of this beautiful home.

Glazes, decorations and forms are all traceable clues that can be used to identify pottery fragments. Even small pieces of a transferware or spatterware saucer reveal information about the time period in which it was made and the people who would have owned such things. This story is about a fragment of white ironstone that was anxious to reveal its secrets.

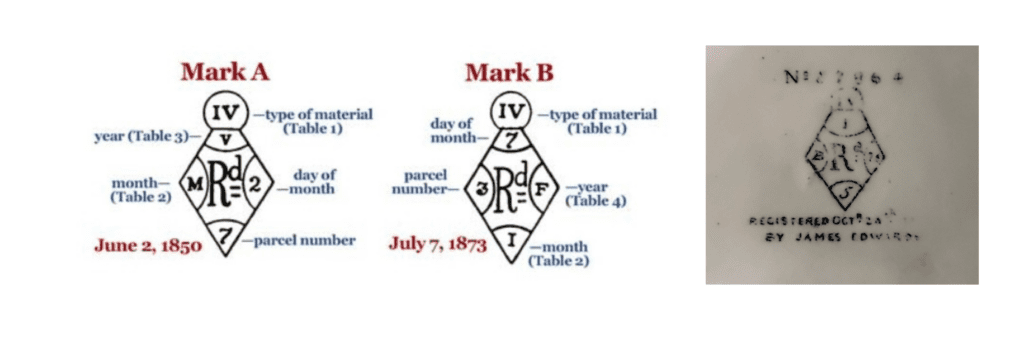

At first glance the piece shows itself to be the fragment of something that once had a handle. The base is intact and octagonal in shape with crisp lines and a smooth white finish. The underside is stamped with a diamond-shaped English registry mark, a symbol that any good ceramics researcher will immediately recognize. This mark was used by the English patent office from 1842-1883 to identify pieces of English pottery or porcelain and once you know how to read it, it will tell you the exact day, month and year that the design for the item was registered. Letters and numbers appearing in the four corners of the diamond allow you to decode the information. The diamond mark on our piece was used from 1842-1867 (Mark A) while a slightly different mark was used from 1868-1883 (Mark B). By consulting a table showing the codes for type of material, year and month, our mark can be deciphered as follows: “IV” in the circle at the top of the diamond tells us that the piece is ceramic, rather than wood, metal or cloth; “I” in the top point of the diamond stands for 1846; “B” in the left point of the diamond stands for October; “26” in the right point is for the day of the month and the “5” at the bottom of the diamond tells us that this was part of parcel number 5. So we know that the design for the English ceramic piece found in our garden was registered with the English patent office on October 26, 1846.

We are also very fortunate that the maker’s mark is also intact on this piece and appears below the patent mark. While it is very difficult to read, it says “Registered October 26, 1846 by James Edwards.

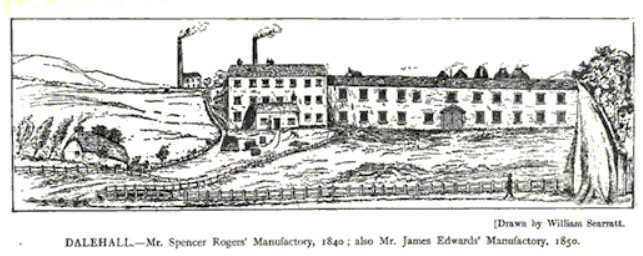

James Edwards was born in 1805 in Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire England. James was the son of a potter in an area of England which continues to this day to be known for its many potteries. He was working with pottery from a young age and at 14 became an apprenticed thrower under a man named Spencer Rogers at Dalehall pottery in Burslem. Burslem is one of six towns that form the city of Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, England. In the years to come James Edwards worked in several regional potteries as a manager and then in partnership with other potters running his own company. In 1842, he purchased the Dalehall pottery where he had once apprenticed and over the next 18 years worked to enlarge and extend the potteryworks, installing all the latest machinery until the company’s output was more than 6 times what it had been when he purchased the property.

James Edwards was a pioneer of white ironstone china which he made almost exclusively for export to markets in the US and Canada. In 1851, James brought his son Richard into the operation as a partner and for the next 10 years they ran the pottery together. James retired in 1861, leaving Richard to manage the company alone. In 1882, Richard sold the pottery to Knapper & Blackhurst.

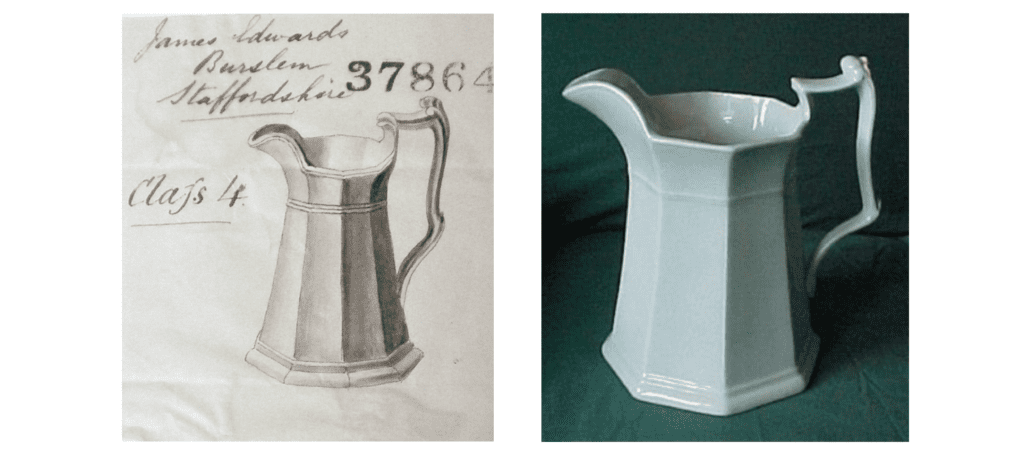

Our fragment of James Edwards white ironstone also has a number which reads “37864.” As luck would have it, James Edwards’ design catalog still exists today and we can see what our small fragment would once have looked like. Design 37864 is for a Full Panel Gothic shape cream jug.

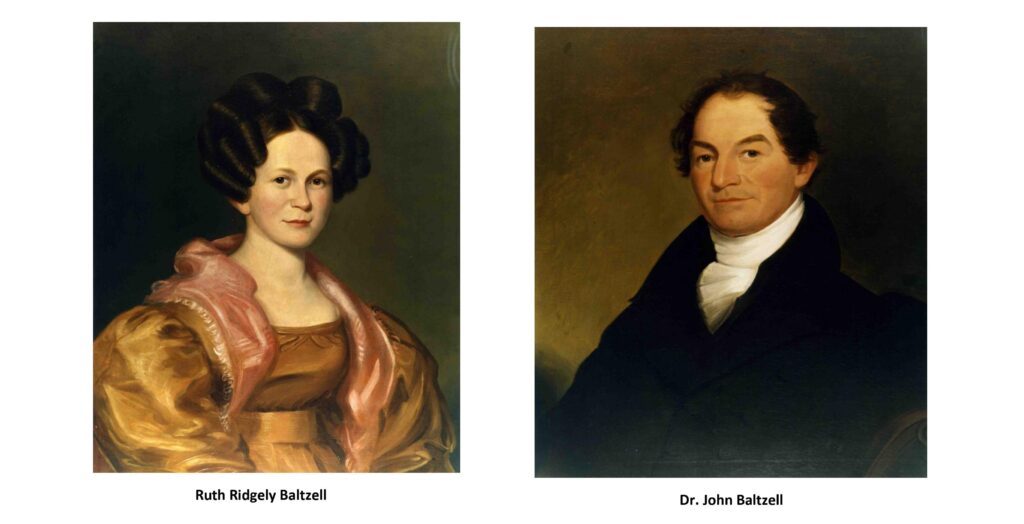

What can this little cream jug tell us and how is it important here in Frederick, Maryland, more than 3,500 miles away from the town where it was made? The date of the pitcher tells us that it most likely belonged to the original owner of our property and the builder of our house, Dr. John Baltzell. Dr. Baltzell bought the property here on the corner of East Church Street and Maxwell Alley in 1823 and we believe, the house was built by 1825. He and his wife Ruth, lived in the home, where at least the 8 youngest of their 10 children were born. It is believed that Dr. Baltzell may have seen his patients from an office in basement which would have originally had its own private entrance from the alley. The family lived in the house until John’s death in 1854 when the house was sold.

Dr. Baltzell was a prominent citizen of Frederick and a much respected doctor, a tea service or table settings imported by an English manufacturer would have been the height of luxury at the time and would have found an appropriate home among the Baltzell’s belongings. Aside from reproductions of portraits of John and Ruth Baltzell, Heritage Frederick has never before had an object that we knew to have belonged to them. While an inventory of Dr. Baltzell’s property remains, we are left to speculate which objects on the list might be related to our 8” English cream jug. When and how was it broken and when was it tossed into a garbage midden on the property?

The fragment of Dr. and Mrs. Baltzell’s full panel Gothic cream jug will be on view, along with several additional artifacts uncovered during the 2000 excavations, in a new installation of the house’s history due to open in 2024.

September 1, 2023 by Amy Hunt, Heritage Frederick Curator