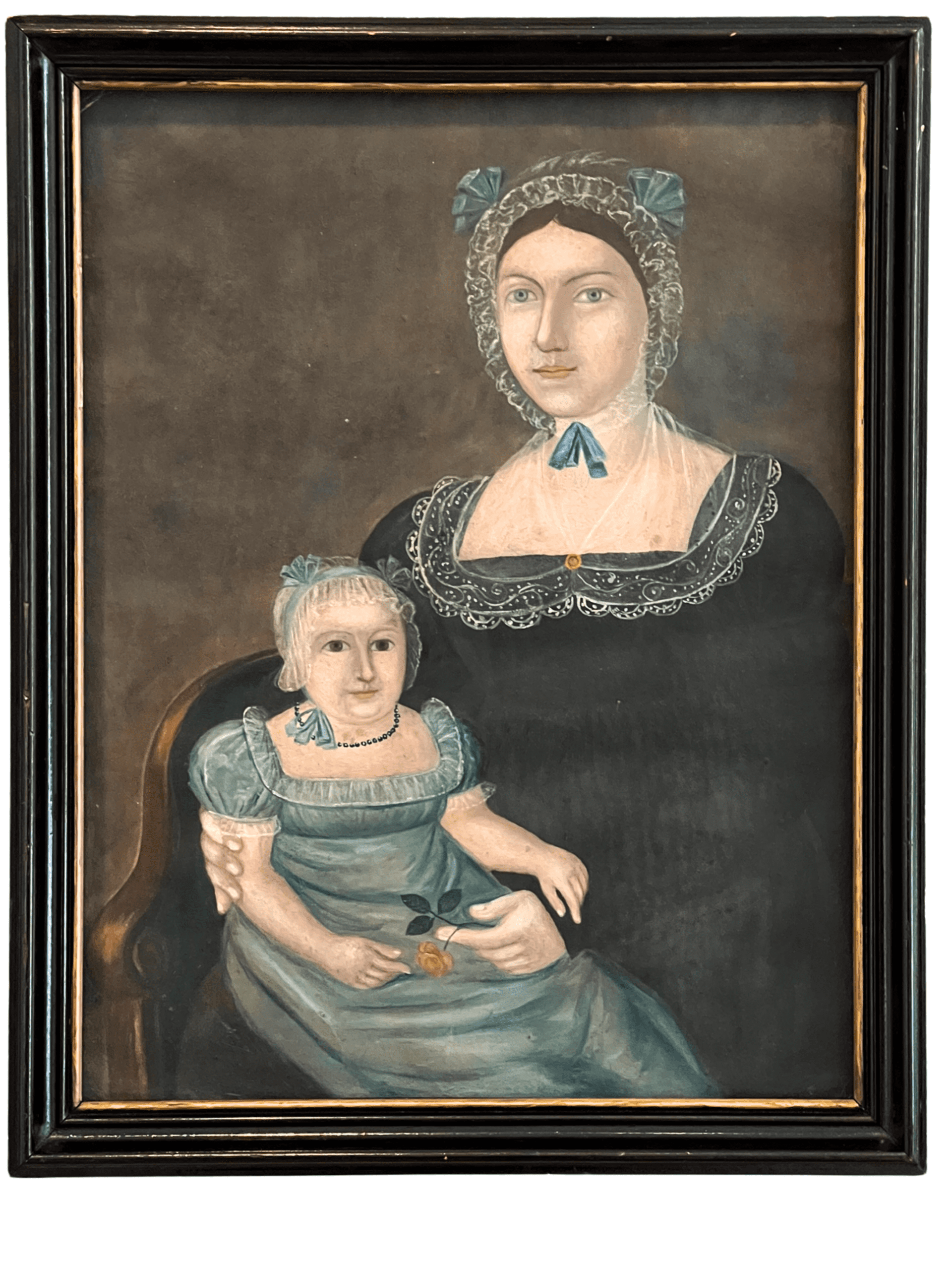

The Kleins, by

Joshua Johnson is considered the first professional, Black portrait artist in the United States. He was born in Baltimore County, MD in about 1763, the son of a White, itinerant farmer named George and an enslaved mother whose name remains unknown. At his birth, Johnson was owned by William Wheeler, a small-scale farmer who likely also owned Johnson’s mother. Records show that George purchased his son from Wheeler in 1764, an action that would have allowed father and son to stay together. Scholars agree that George did not buy his son as an investment or to subject Joshua to life as a slave. There are many examples of Freed Blacks or White members of mixed-race families purchasing relatives to prevent separation. But, George likely had no money or property to leave his son, and laws required that freed slaves needed a means of earning money as a condition of their freedom. So, while Johnson remained technically the property of his father, these formative years together likely were used by the father to ensure his son learned skills in a trade that would support him as a free man.

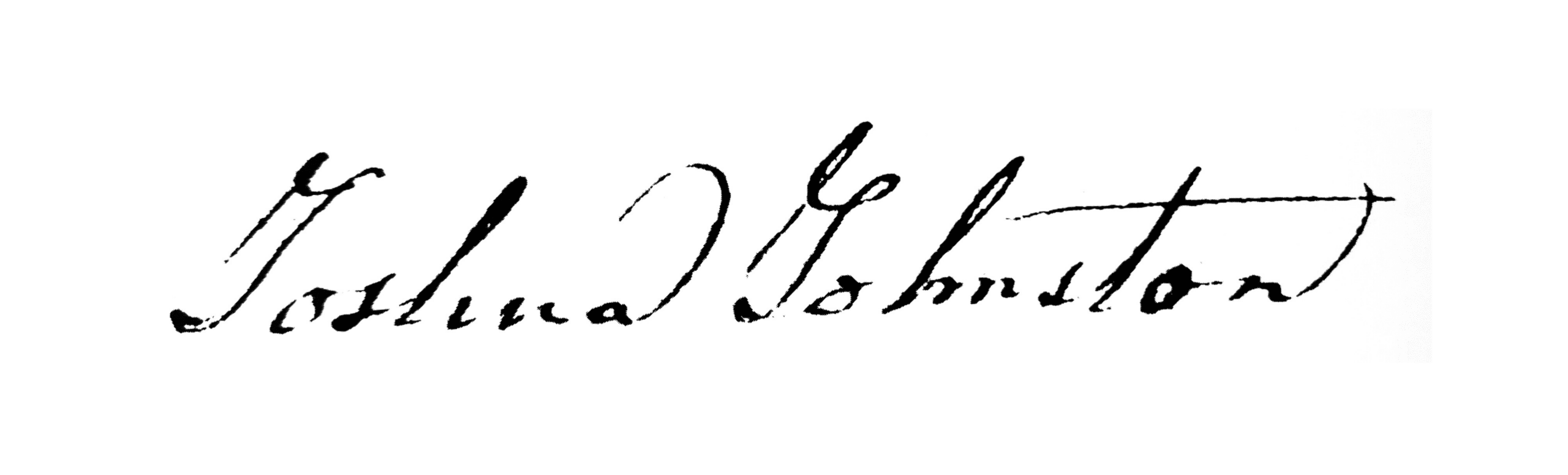

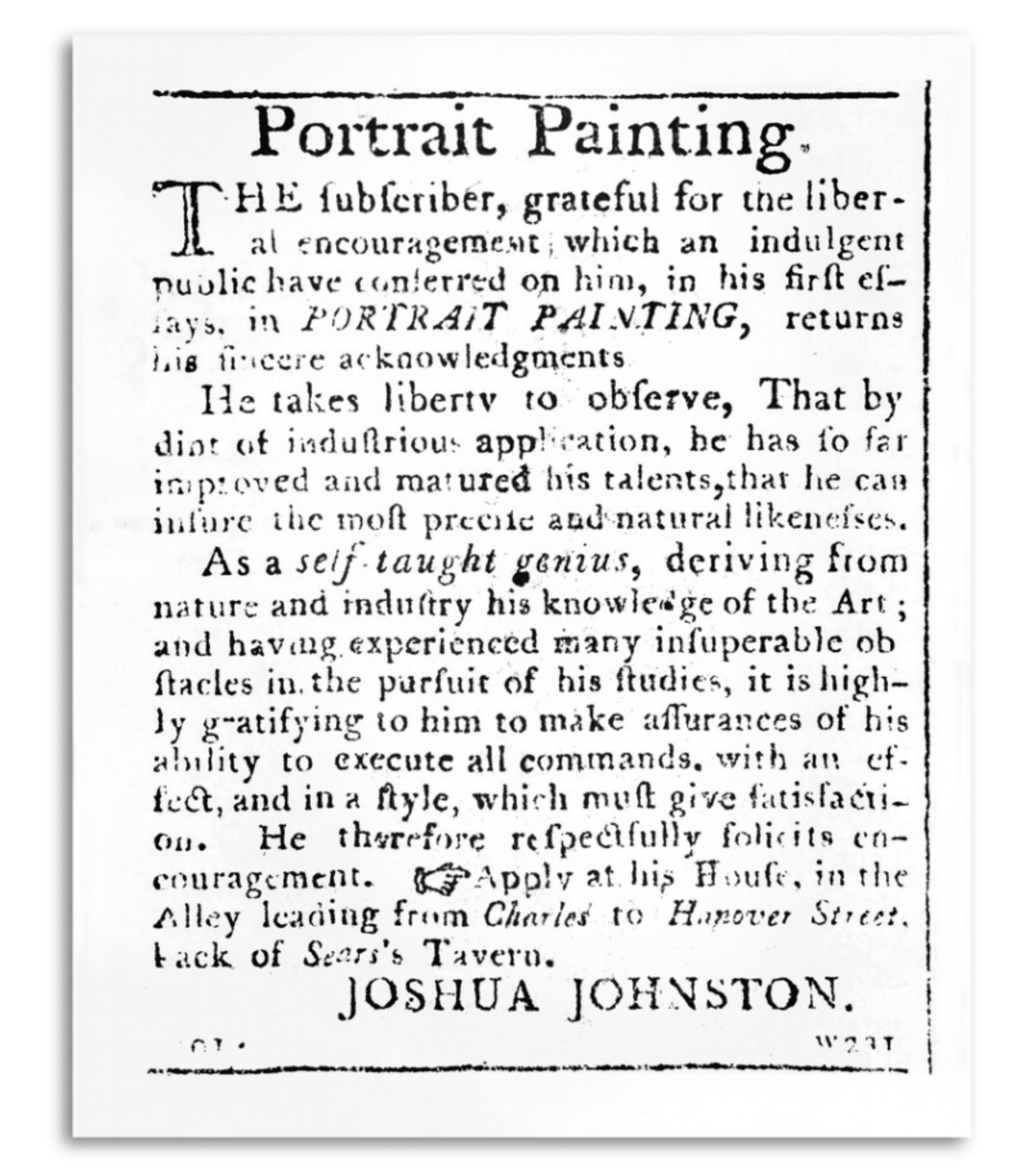

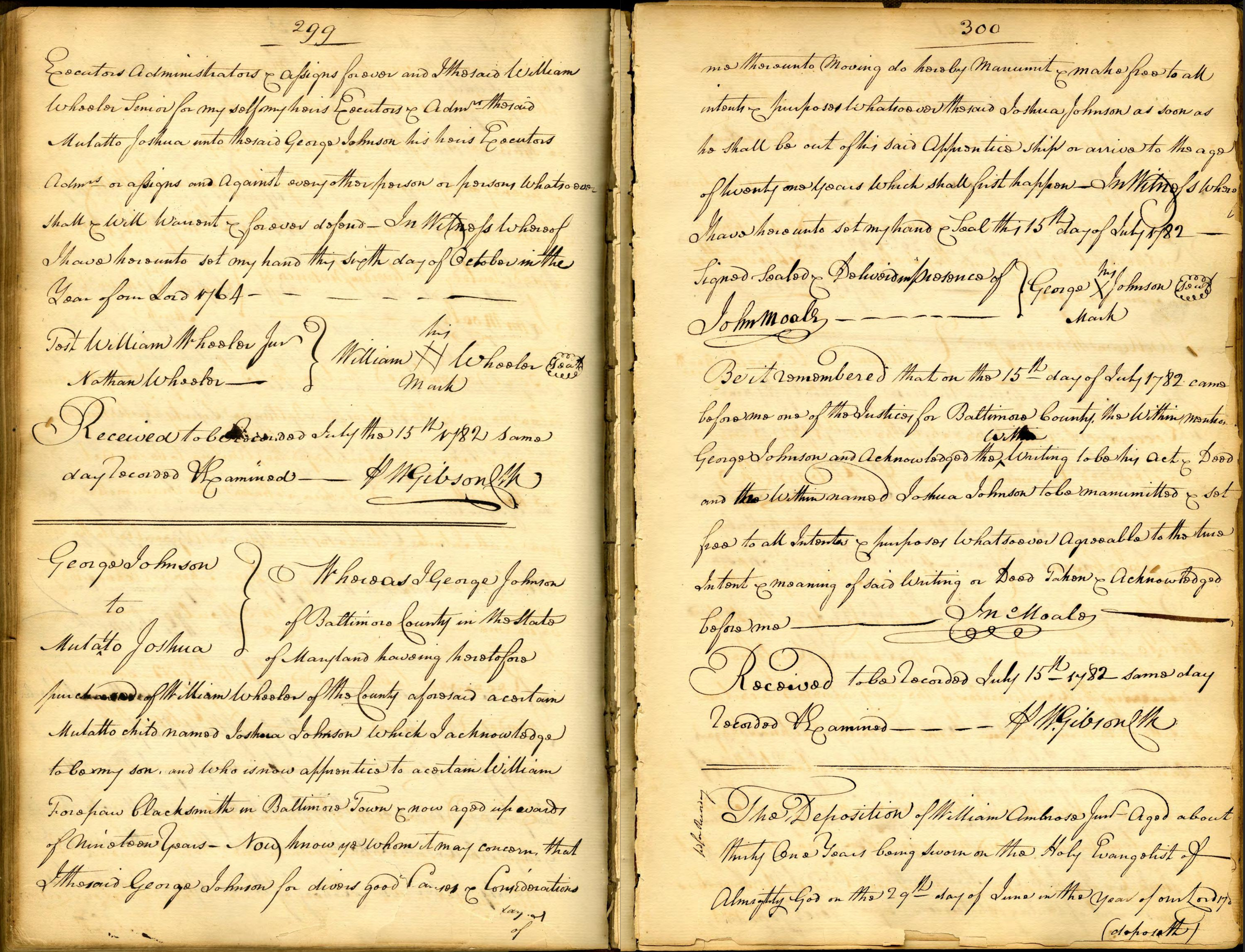

George formally freed his son in 1782; Johnson’s manumission paper, the legal deed that conveyed freedom, confirmed that George was Joshua’s father and that he agreed to free him following the completion of an apprenticeship with a blacksmith in Baltimore City or his 21st birthday, whichever came first. Johnson began his free life in Baltimore as a journeyman blacksmith by 1784; it isn’t clear how or when Johnson learned to read and write, but he was literate. It’s also unclear how he supported his family except to infer he earned money as a blacksmith initially. But, in 1795, Johnson advertised himself as a portrait painter. His exposure to art, training in art, and knowledge of art remain unknown, but it’s fair to take Johnson at his word: he was self-taught.

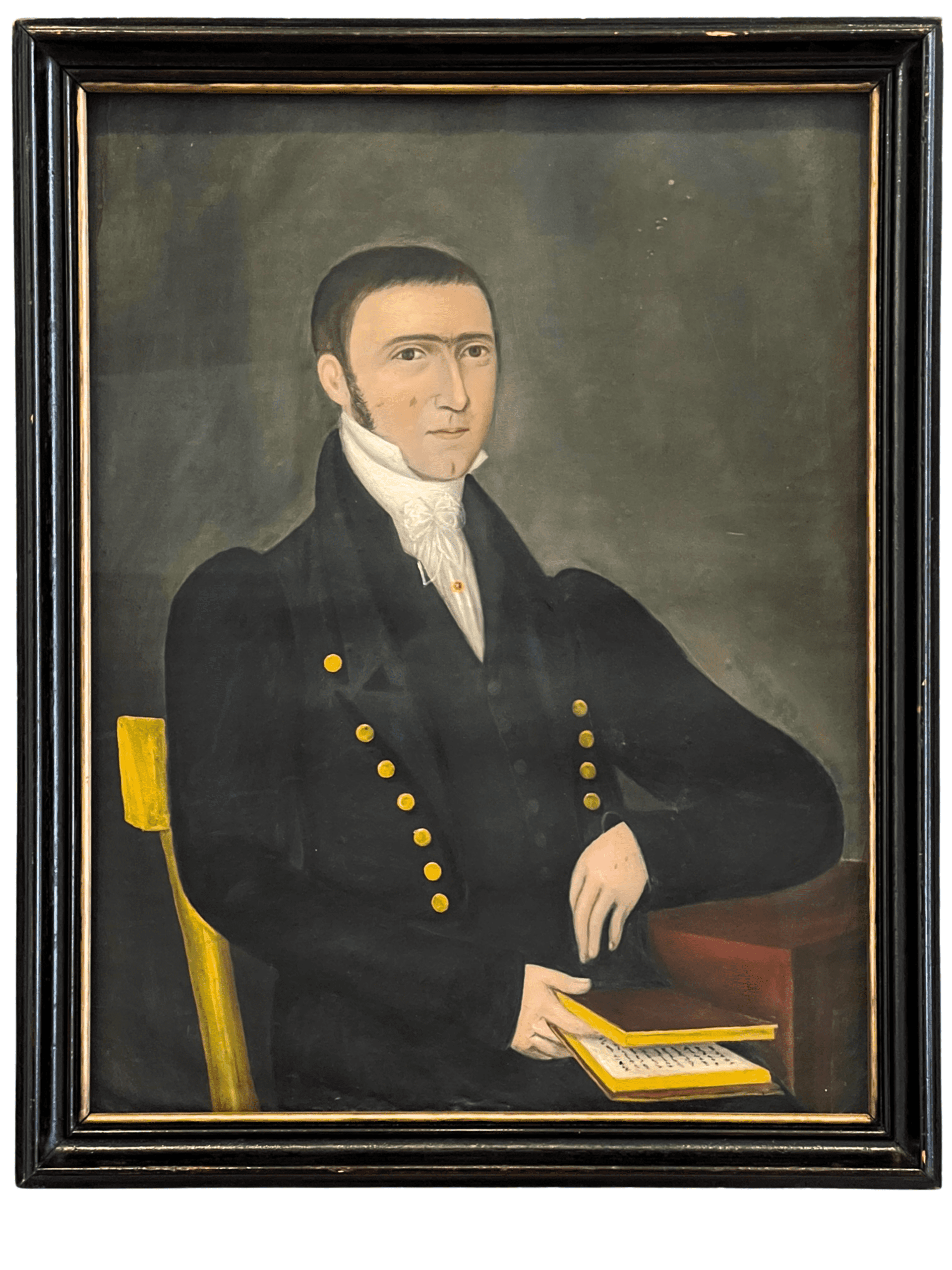

Johnson’s subjects included a diverse clientele but most were his neighbors: middle-class families, rising merchants, local political officials, ship captains, and religious leaders. While many of his patrons had abolitionist leanings, Johnson almost certainly had to come to terms with painting sitters who were slave owners. Johnson’s style often is labeled “naive” or “folk,” which is intended to differentiate his artistry from what commonly is understood to be classical or refined. But, his self-taught style matched his clientele; he didn’t paint the rich and famous or high society. Many of the known works attributed to Johnson look very similar, as if he painted the background minus faces and then filled in faces when he secured a commission.

Johnson moved frequently within Baltimore and following a move to Anne Arundel County around 1825, the trail of his life and career are lost. Most biographies list Johnson’s death as circa 1824 for this reason but no documentation of his death has yet been found. He did not sign his paintings and therefore his name and works were forgotten for a time. In 1939, J. Hall Pleasants, a genealogist and art historian, released what little information he had discovered about Johnson, identifying 13 works by him. Subsequent research by the Maryland Center for History and Culture over the past 30 years have revealed more information about Johnson.

Paintings by Joshua Johnson are rare and are included in prominent museum collections such as the National Gallery of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, the Maryland Center for History and Culture, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Virginia Museum of Fine Art. While all other known works by Johnson are painted on canvas, the two held by Heritage Frederick are very unusual in that they represent the only confirmed examples of his work done on paper.

Frederick Klein was born in 1790 in Walheim, Württemberg, Germany. He is thought to have fought under Friedrich Wilhelm, Crown Prince of Württemberg, alongside Napoleon during the invasion of Russia in 1815. Following the war, Klein immigrated to America; he spent his first few years in the country working in bakeries throughout Pennsylvania before traveling to Baltimore to set up shop for himself. Klein married Anna Lillich, also a native of Württemberg, and from about 1820-1840 they lived in Baltimore, raising their children while Frederick ran his bakery on Pearl Street. Suffering from ill health, Klein moved the family out of Baltimore and into the rolling hills of Frederick County where he set out on a new path as a farmer. He purchased 280 acres in Liberty then, 19 years later, a small farm of 45 acres three miles west of Frederick City, which he purchased from Jacob Culler.

The Kleins are pictured here in the early years of their marriage, Anna holding their first born child, E. Frederick Klein, Jr., who was born in about 1822 and died in infancy. These paintings were donated to Heritage Frederick in 2007 by the great, great, great grandson of the sitters, Mr. Charles Harold Klein, of Lubbock, Texas.