What is “money?” Essentially, it’s any item that two people agree has value for them. If a country doctor accepts payment in chickens or eggs, those commodities serve the purpose of money. Native Americans valued beads, shells, and animal furs. Romans traded coins forged from gold, silver, and copper.

For nearly two centuries after European settlers arrived in America, the colonists attempted to conduct business without banks or an American currency. Gold and silver – coins or nuggets – were the precious metals that represented value in commercial exchanges, but the supply was limited.

The English government purposefully restricted colonial manufacturing, business formation, and an independent money supply. As a result, the colonies remained dependent on England for finished goods – fabrics, furniture, tools, and more – while they provided the source of the raw materials for English factories. Continued use of English money was convenient but made the colonies subservient to a money supply over which they had no control.

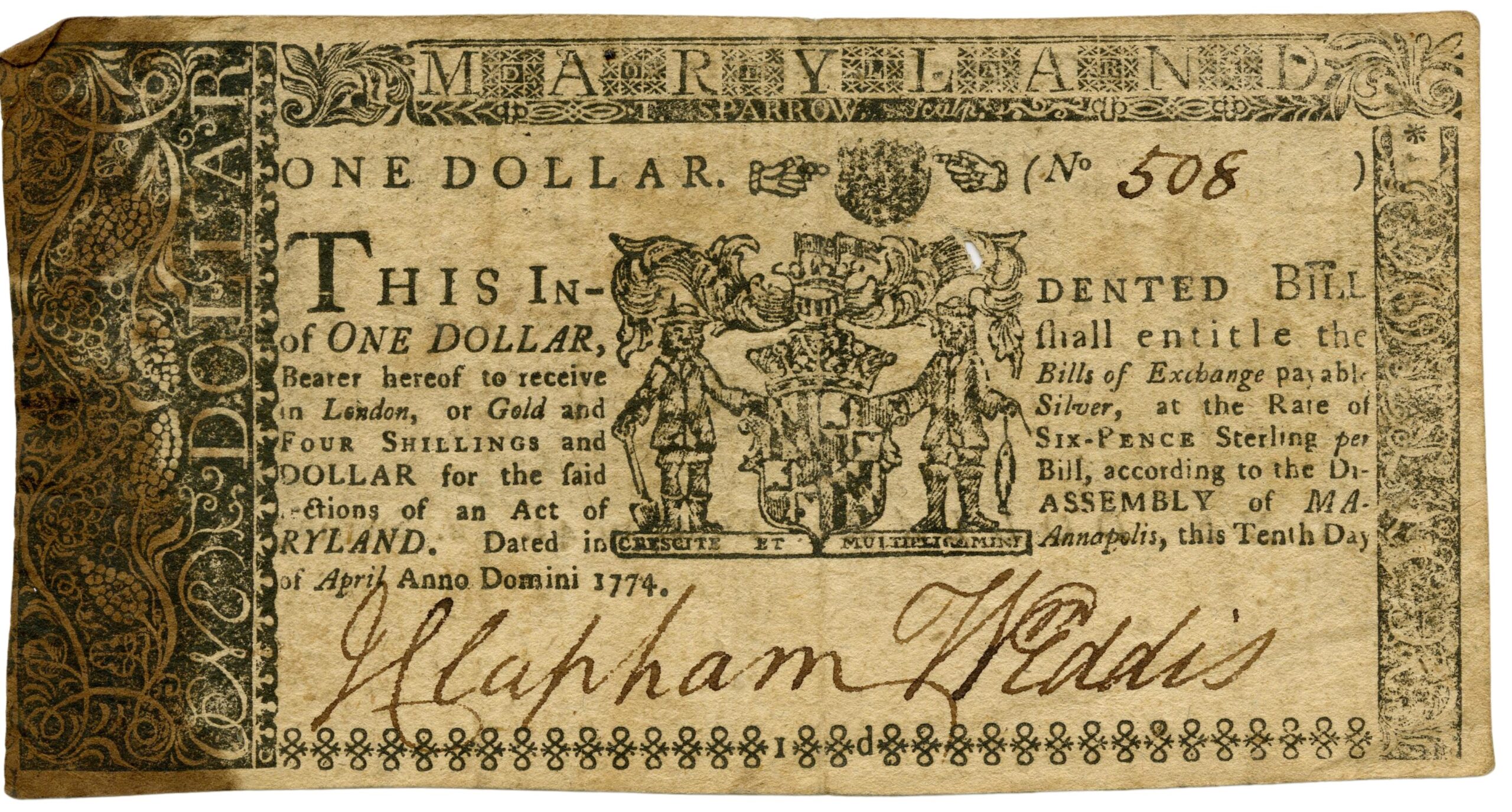

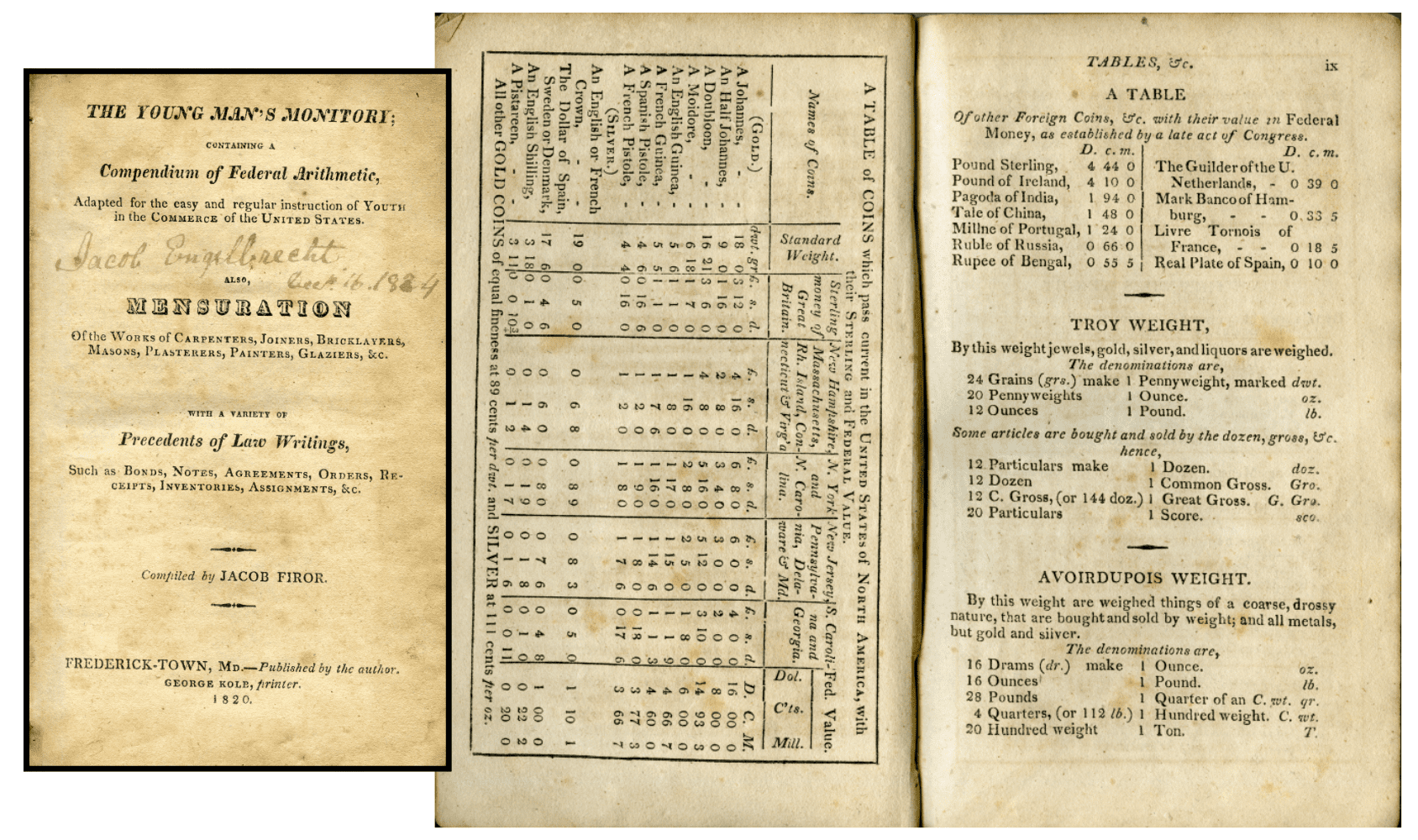

Money in colonial America included various foreign coins, governmental and private paper currency, and monetized commodities. In 1786, the American Congress adopted the Spanish silver dollar as the monetary standard for the United States.

Colonial governments eventually passed laws assigning values to foreign coins at different measures, so a single coin represented different values from one colony to another. To create new money, colonies substituted commodities, particularly tobacco, and assigned a value by weight. Then, colonists paid for goods or taxes using tobacco as “money.” Planters also routinely traded tobacco for imported goods.

Whatever the means of payment, the standard measures of value remained the English system, as defined by each colony. So, the means of payment might be tobacco or a Spanish coin, but those items each were worth a set value in pounds, shillings, and pence.

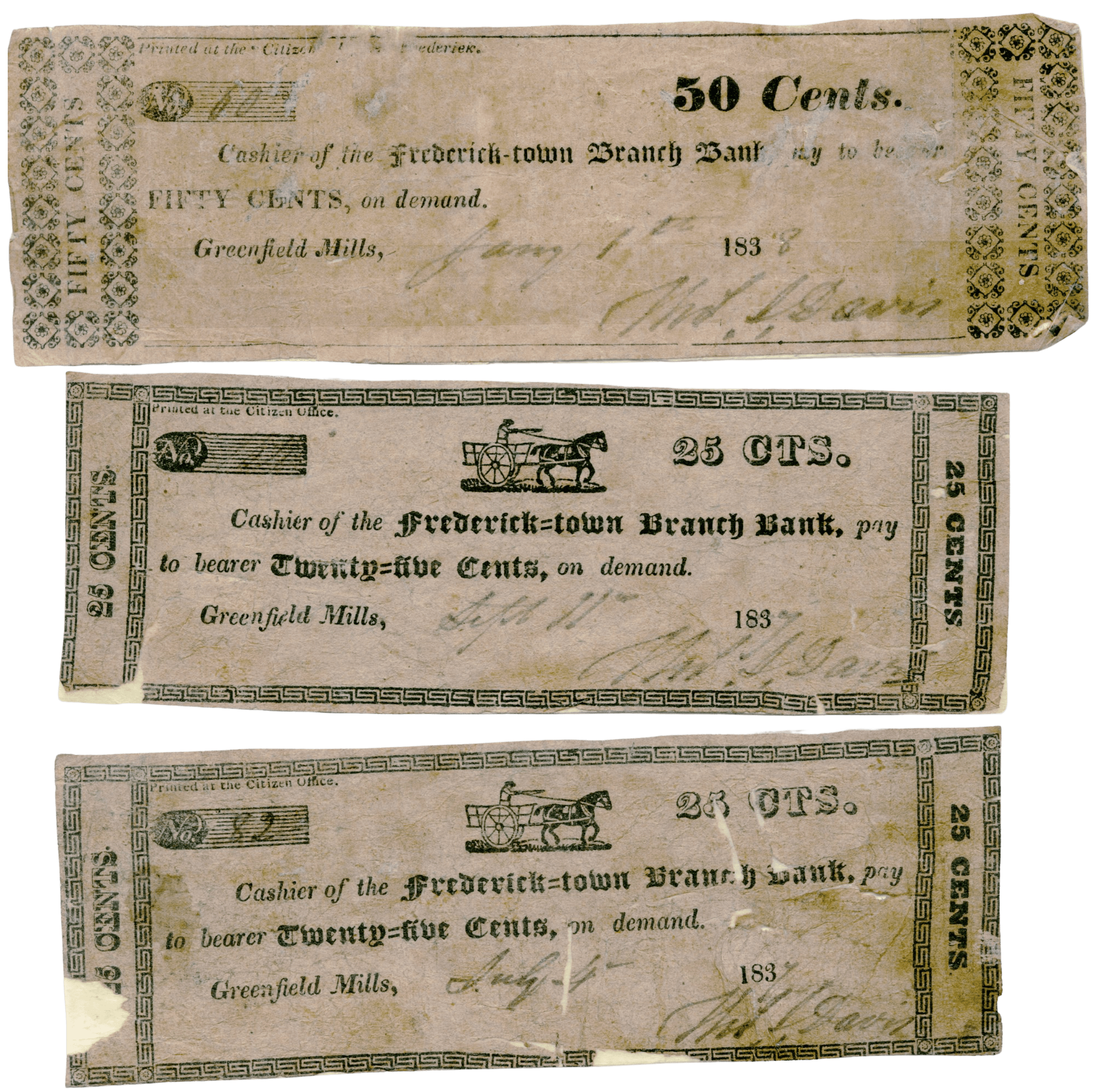

Colonies also created paper currency, such as a warehouse receipt or note for tobacco held at public warehouses. A farmer could redeem his note at the warehouse and be “paid” from the inventory in stock. Individual merchants and mills also created paper, which was tied to the inventory of the seller – a person could obtain the paper and redeem it for flour, for example, or other commodities. This currency could also be used for buying items or bartering before it came back to the issuing merchant. Stability was a constant problem, because the value of commodities and coins changed continuously and from colony to colony and the long-term success of a store or mill was unpredictable.

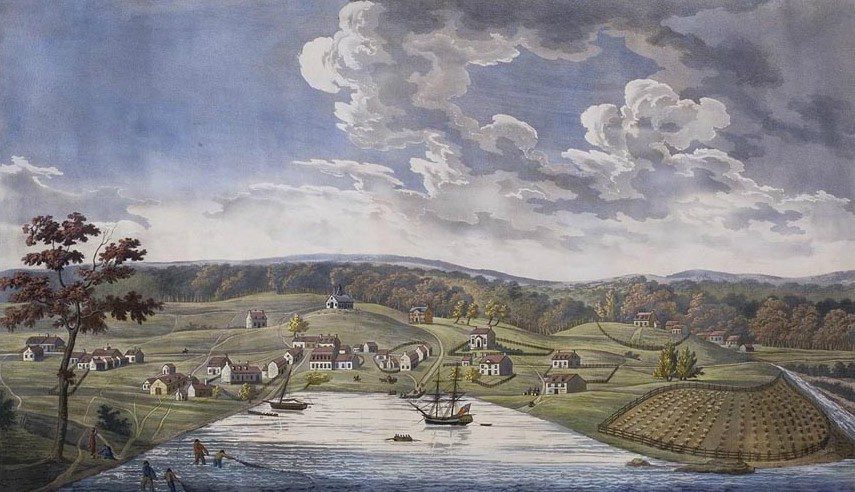

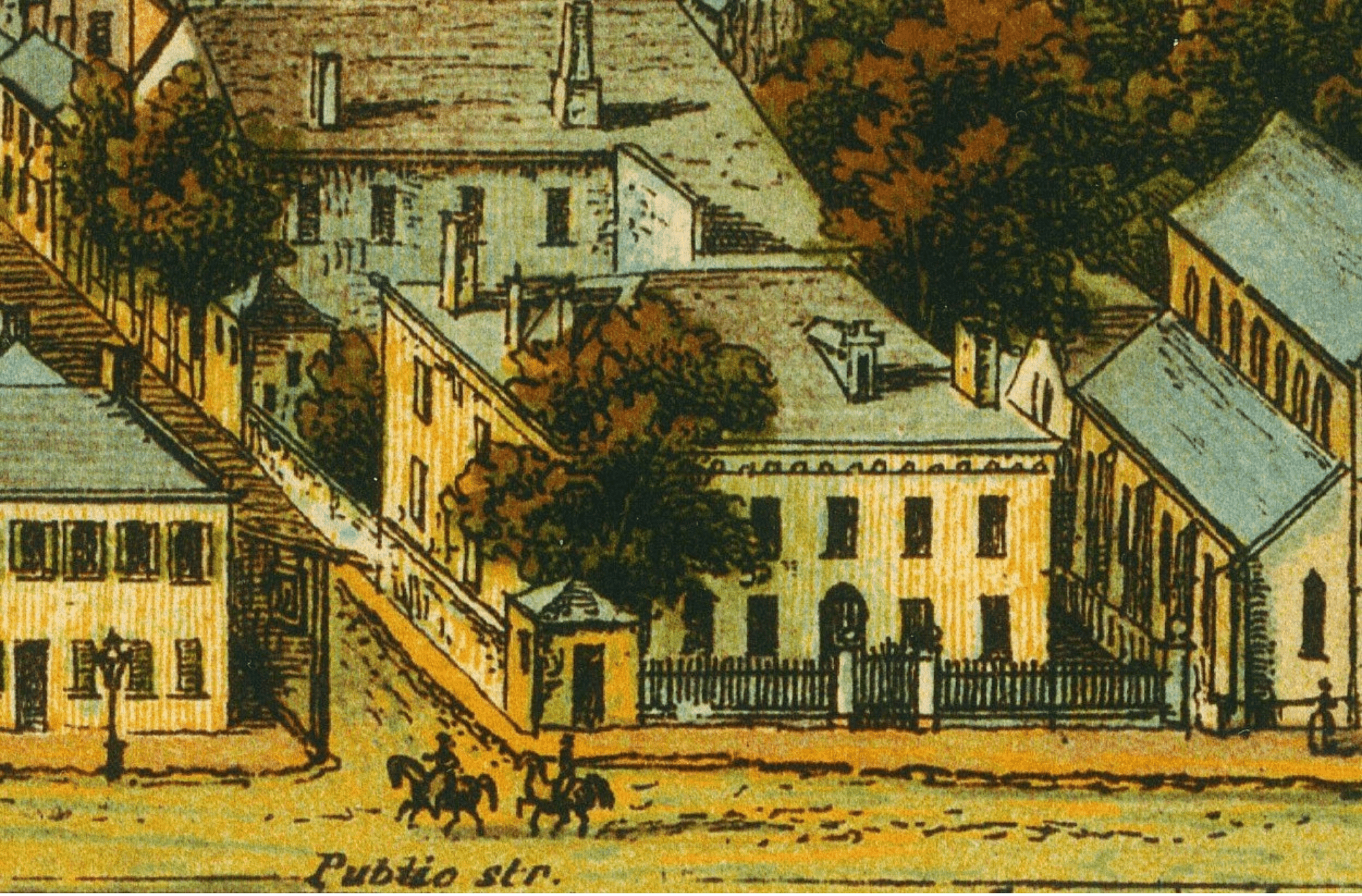

In the second half of the 1700s, economic growth eventually outran the capacity of tobacco to function as a method of payment. Foreign demand for wheat- and its high price relative to tobacco – led to cultivation of grain across Maryland. German immigrant farmers flocked to the Monocacy and Antietam Valleys, and Frederick Town and Hager’s Town arose as inland marketplaces. The export trade of wheat and flour helped boost Baltimore as a port city and trading place.

Dockside warehouses emerged to store produce brought in from the wilderness that would go out by ship, and retail shops emerged to meet the demand by farmers for products they’d take back to the wilderness. The wholesale merchant became the key to the new system – buying trade inventory from the farmer on one hand and selling imported goods to retailers with the other.

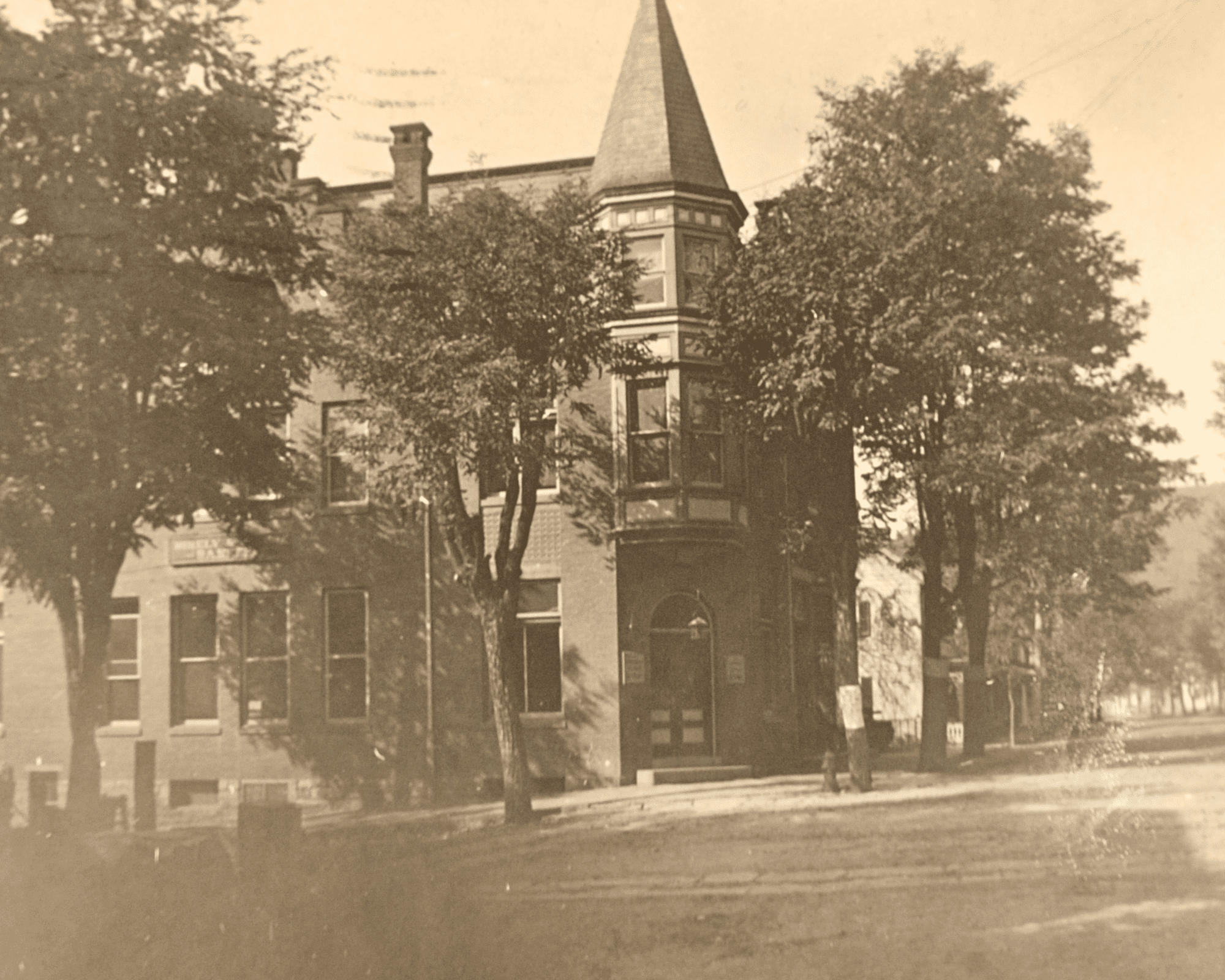

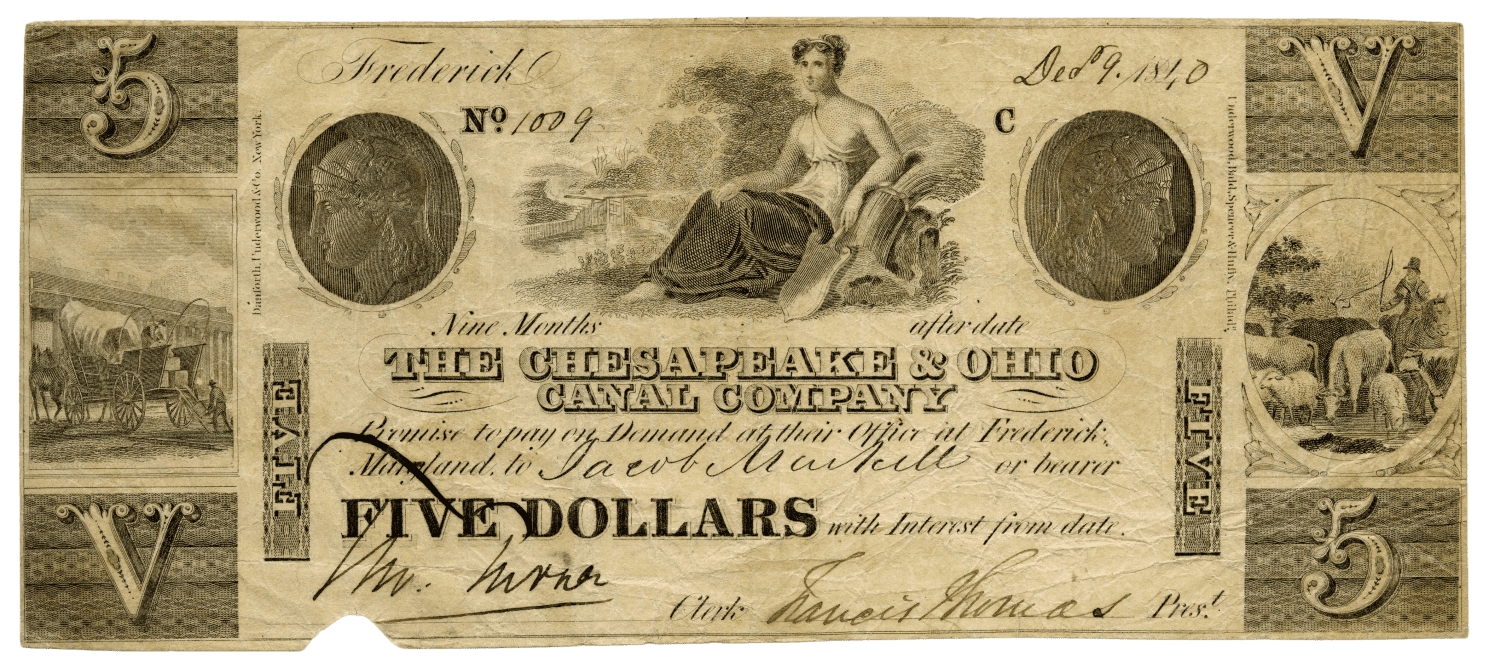

Ultimately, more people and expanding business activity necessitated an increased volume of currency and credit. During the 1780s, seven states authorized the issuance of bills of credit, which functioned as a substitute for currency. The new US Constitution provided stability by forbidding states to coin money and stipulating that gold and silver were the only legal tender. States could not issue currency, but they could charter private banks, which could issue banknotes. In 1790, Maryland granted a charter to the Bank of Maryland. Within 14 days, the bank had raised $200,000 in stock subscriptions toward its $300,000 limit. In 1795, the Bank of Baltimore followed. In 1804, Farmers & Merchants Bank joined them. In 1791, Congress created the Bank of the United States, then in 1792 Baltimore became home to one of eight branches of the bank. Each branch could issue currency in the form of banknotes up to a limit set by Congress. The notes represented a promise to pay backed by gold and silver reserves.

The Bank of the United States had been a contentious issue since its founding. The first institution went out of operation in 1811, but by 1816 there was a Second Bank of the United States. In 1828, Andrew Jackson campaigned for president in opposition to the Bank, which he blamed for the country’s depression. The Bank was federally chartered but operated as a for-profit entity; Jackson saw the Bank as unaccountable and run by elitists who served shareholders and controlled the economy at the expense of farmers, artisans, and laborers.

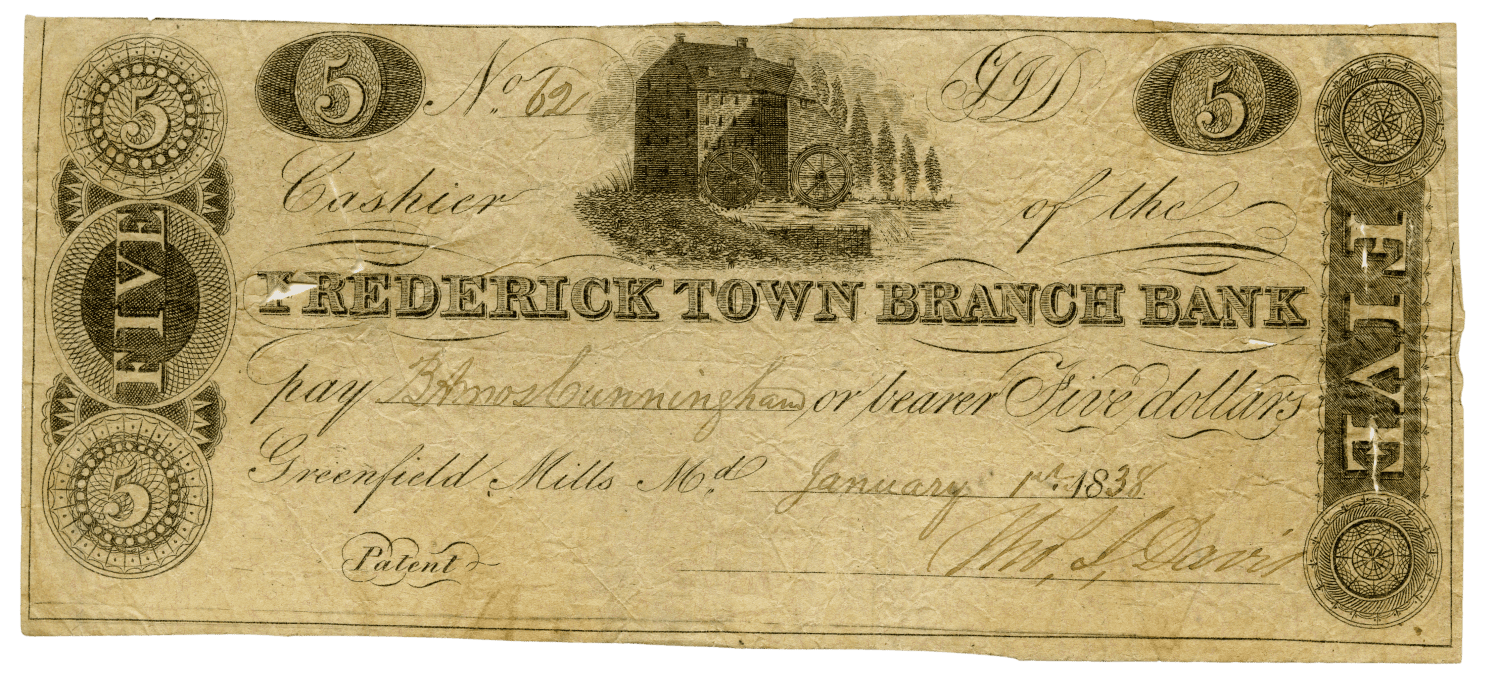

In 1833, Jackson signed an executive order diverting Treasury receipts from the Bank to state banks, causing economic upheaval. The Bank of the United States typically invested in national and international trade. But, state banks invested heavily in land development, land speculation, and state public works projects; this created a speculative boom in the final years of Jackson’s administration and an economic depression that lasted until 1841. Between roughly 1840 and 1860, private and state banks issued their own currency, also called notes or script. The system created by Andrew Jackson ultimately involved haphazard formation of private and state banks, rampant fraud, little regulation, and little public trust in the institutions. Banks failed with regularity.

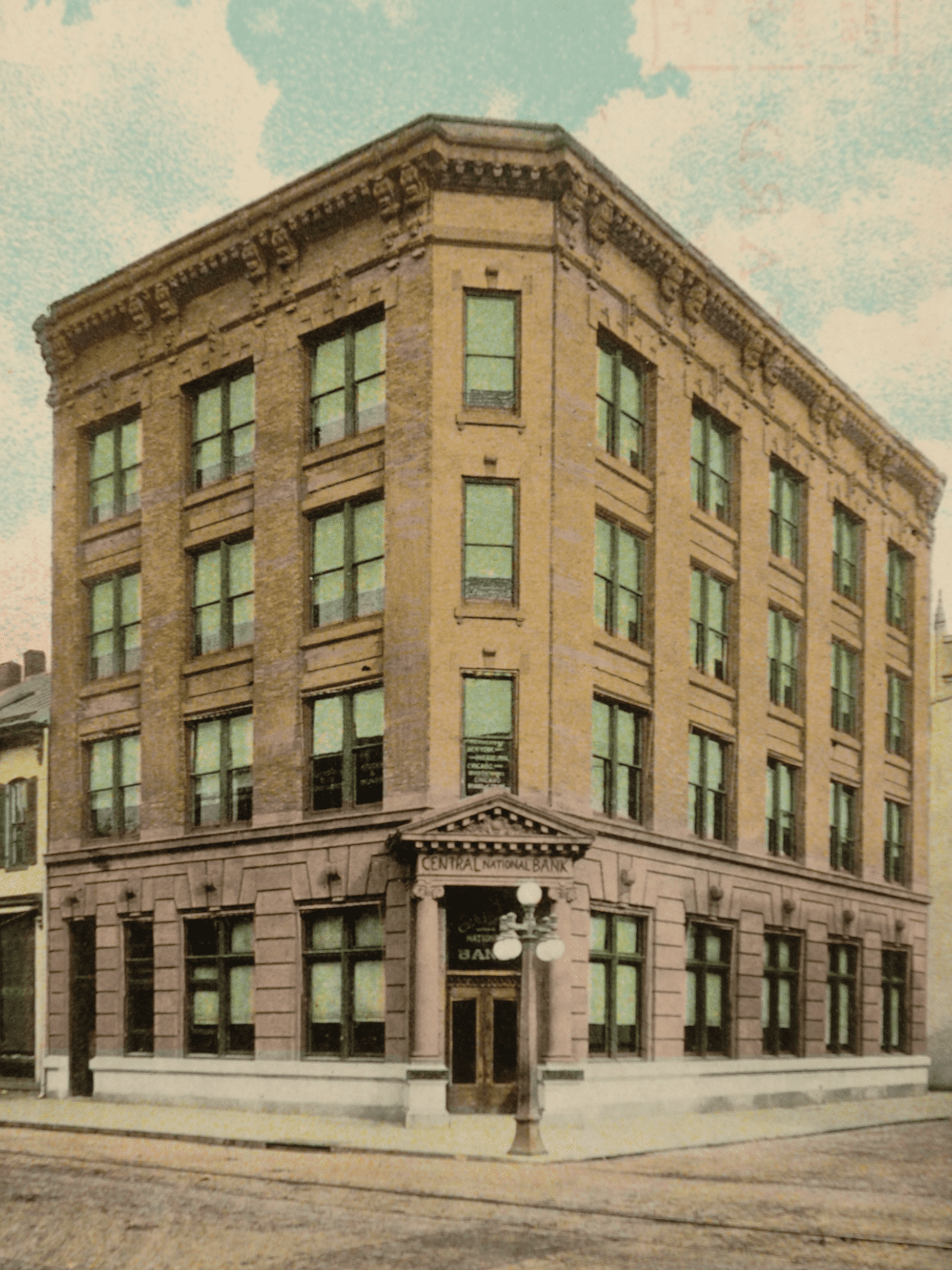

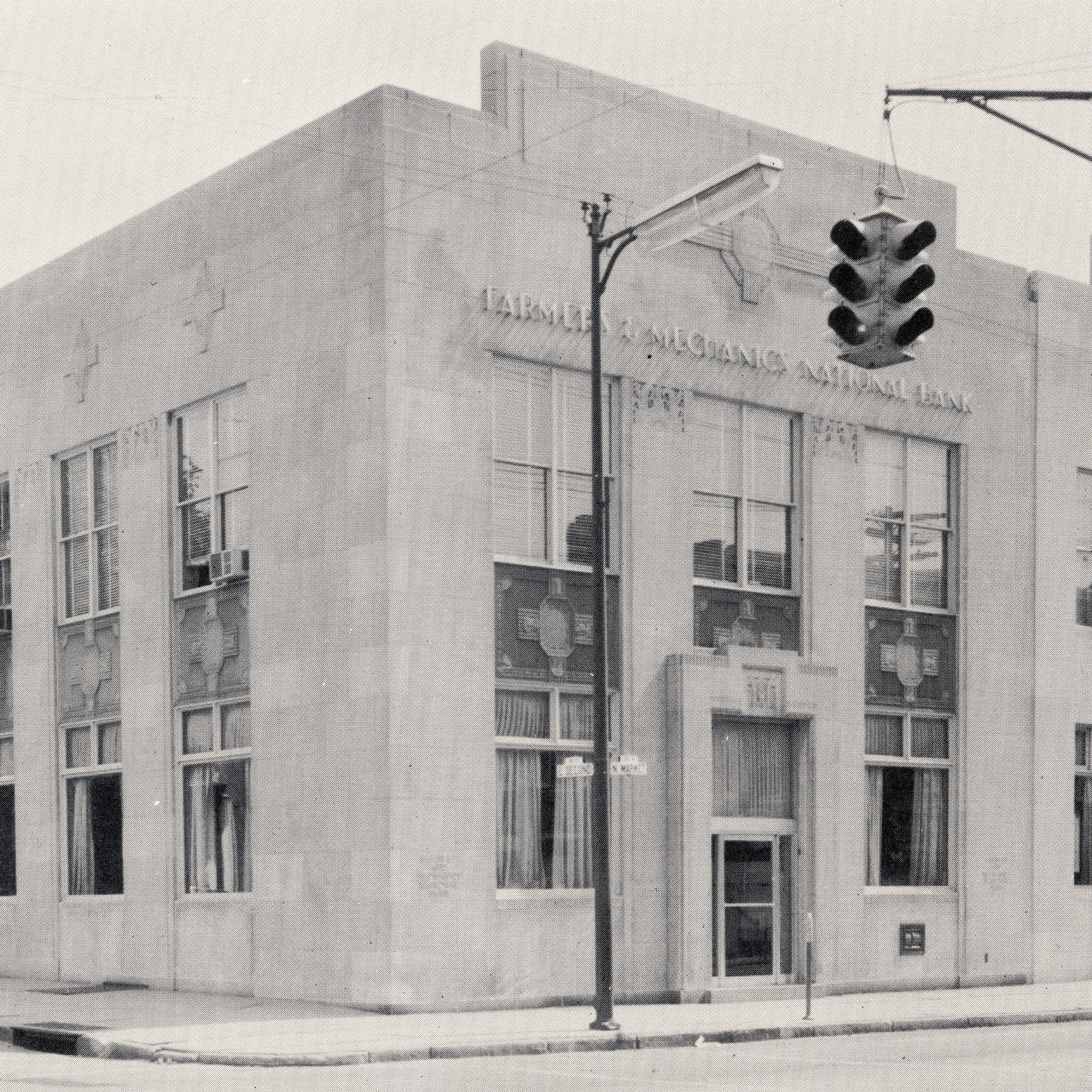

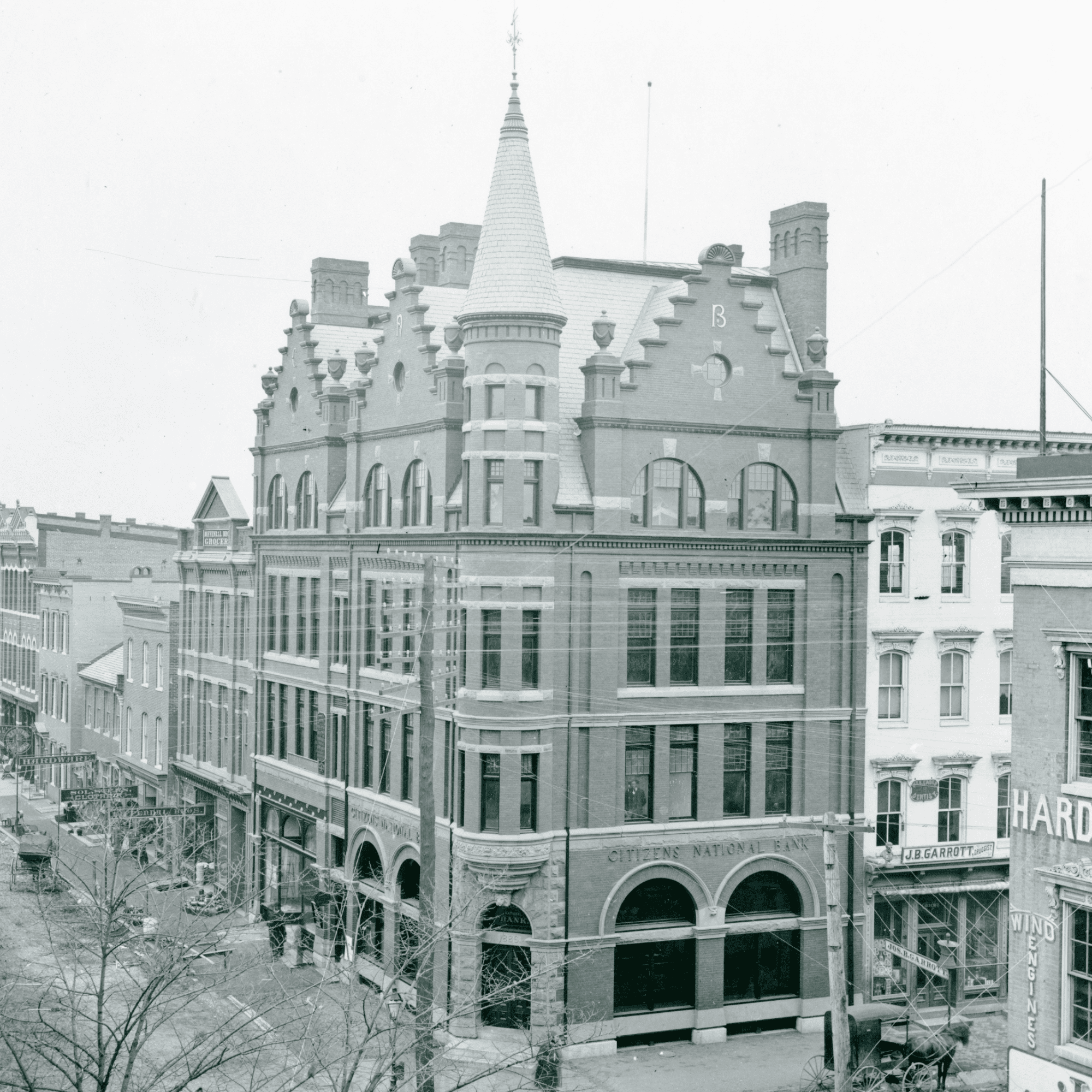

On February 25, 1863 Abraham Lincoln signed the National Currency Act, which established a national currency secured by the United States government. Subsequently, more than 12,000 “national” banks issued uniform paper money between 1863 and 1935, including eight in Frederick County, MD. Currency issued by national banks was not uniform in size, design, or color until 1929. Most national bank notes were signed by the bank’s cashier and president. Economic growth in the United States during the first decade in the 1900s made the national – state level – banking system obsolete. Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act in December 1913, which eventually ended the state-level system in August 1935.