Marshall Lingan Etchison

Between 1893 and 1960, Marshall Etchison lived an extraordinary life despite being, we say admiringly, an ordinary man. His formal education concluded with a high school diploma, yet he became a highly-regarded expert in art, history, and antiques. He completed little formal music training, but he spent his adult lifetime giving piano lessons and playing the organ for various Frederick churches. Marshall never owned a car and lived most of his life up and down Church Street, yet he traveled in Europe six times and made friends there who remained in contact with him for years afterward. He drew and painted local scenes, wrote poetry occasionally, and hand-crafted at least one magnificent Christmas card for his mother. For good measure, he served his country during World War I.

In 1926, while traveling in Europe, Marshall wrote a letter to the editor of the Frederick News decrying the ruination of Frederick’s old landmarks and homes and the coincidental ruination of the city’s historic atmosphere – in this case, the historic mills along North Bentz Street that would be torn down as Frederick City created Baker Park. In 1936 he wrote a letter in support of restoring and repurposing the Frederick Academy building as a library instead of razing it to make way for a new structure. He was a longtime member of the county historical society who both delivered lectures and served as its president, and the organization named him its curator just a few months before he died in 1960. Marshall’s estate contained innumerable antique furniture and clocks, art, rare books, glassware, including Amelung objects, and lustreware pottery, about which a ceramics curator from the Smithsonian declared at the time, “Your collection of lustre is finer then we have.”

Marshall donated a significant portion of his personal collection to the historical society, and this exhibit honors not only Marshall but his extended family, which has direct links to numerous, signature aspects of Frederick’s evolution and success. The Etchisons surely aren’t the only family in Frederick’s history that touched significant people, events, and companies in the community over generations, so in that way we are sharing their story as one lens through which we can interpret Frederick’s narrative of growth and change.

Everything Old and New

Frederick’s population in 1860 was about 8,100; by 1910 the number was more than 10,000 (23% growth). A coincidental expansion occurred among merchants, taverns, and services like photo studios and tailors catering to the community. Bigger business operations emerged at the end of the century, particularly, like Union Manufacturing, where hundreds of people held jobs. All of those houses and businesses needed desks and chairs; people needed beds and clocks; babies needed bassinets. Throughout all this growth, Henry Nelson Etchison, Marshall’s grandfather, met the demand year after year, from his building on South Market Street.

Henry moved from Jefferson to Frederick in 1866 and quickly became one of its stalwart businessmen and civic leaders. In 1869 he bought the furniture business of James Whitehill and continued growing his capacity to meet consumer demand for 30 years. His son, William Hezekiah Boteler Etchison, (Marshall’s father) joined him in business at just 18 in 1875 and together they filled up the buildings of Frederick with the furniture that enabled the citizenry to keep moving forward and families to keep growing.

Likewise, when a grandmother finally gave her last, or a farmer died from a fall off his tractor, or a baby succumed to diptheria, Henry and William met that need, too, as morticians and funeral directors for their friends and neighbors. There were periods of time when they were named in the newspaper every week for their work. Henry retired in 1899 and died in 1903; William carried on for another decade until an illness limited his capacity to work; he died in 1914. Henry’s brother, John, started his own funeral home in 1848, which became known as M R Etchison and Son after the next generation, McKendree Riley Etchison; the business had a few locations but its last place of operation was the Trail Mansion from 1939 until M R’s son, Hart, sold the business in 1971 to partners named Keeney & Basford.

Albert V. Dixon was a neighbor to the Etchisons in Jefferson where he worked as a farm hand for the Hemp family. An injury and resulting blindness in one of his eyes thwarted Albert’s dream of becoming a doctor, so instead he pursued a career as a funeral director. In 1924, Dixon became the first Black mortician in Frederick County. Shortly after completing the state funeral director’s examination, Dixon moved with his family to 16 South Bentz Street and opened his own funeral home there. He also began working for McKendree Reily Etchison who recognized Dixon’s skill as an undertaker. Dixon performed embalming for the Etchison Funeral Home. Like many other business owners in small towns, and particularly for funeral directors, Dixon ran his funeral parlor from his own residence. Later, he transferred both his family and business to 22 South Bentz Street. At both locations, Dixon struggled to find enough space for all his furniture and equipment. Ultimately, Dixon was invited by his peers at the M R Etchison Funeral Home on Church Street to use their facility. He worked there until declining health forced Dixon into retirement in 1939.

Industrial Frederick

After the Civil War, America slowly evolved from self-sufficient farmsteads to an economy driven by growing industries, including oil, steel, lumber, electricity, mining, and garment manufacturing. Mechanization made factories more productive, and factory jobs offering reliable wages attracted workers in large numbers.

In Frederick, five men organized the Frederick Seamless Hosiery Company in 1887. Within a few years, the company built a 35,000 square-foot factory on East Patrick Street to house machinery for producing hosiery for men, women, and children using cotton, silk, and wool. In 1889, the owners reincorporated the business as the Union Manufacturing Company. At its peak, Union Manufacturing employed around 350 workers and opened branch factories in Emmitsburg and Thurmont.

Monocacy Valley Cannery on Commerce Street, founded by Charles Ross, Jr and Charles Staley in 1898, employed more than 500 seasonal workers; the company eventually opened a second plant in Walkersville. Processing emphasized peas and corn but also included many other fresh, local fruits and vegetables. At its peak, Monocacy Valley produced 200,000 cans each day. Both founders gained experience working for the Louis McMurry Canning Company, which opened in 1869 between All Saints, Bentz, and South Streets. Dozens of other canneries dotted the county and surrounding area.

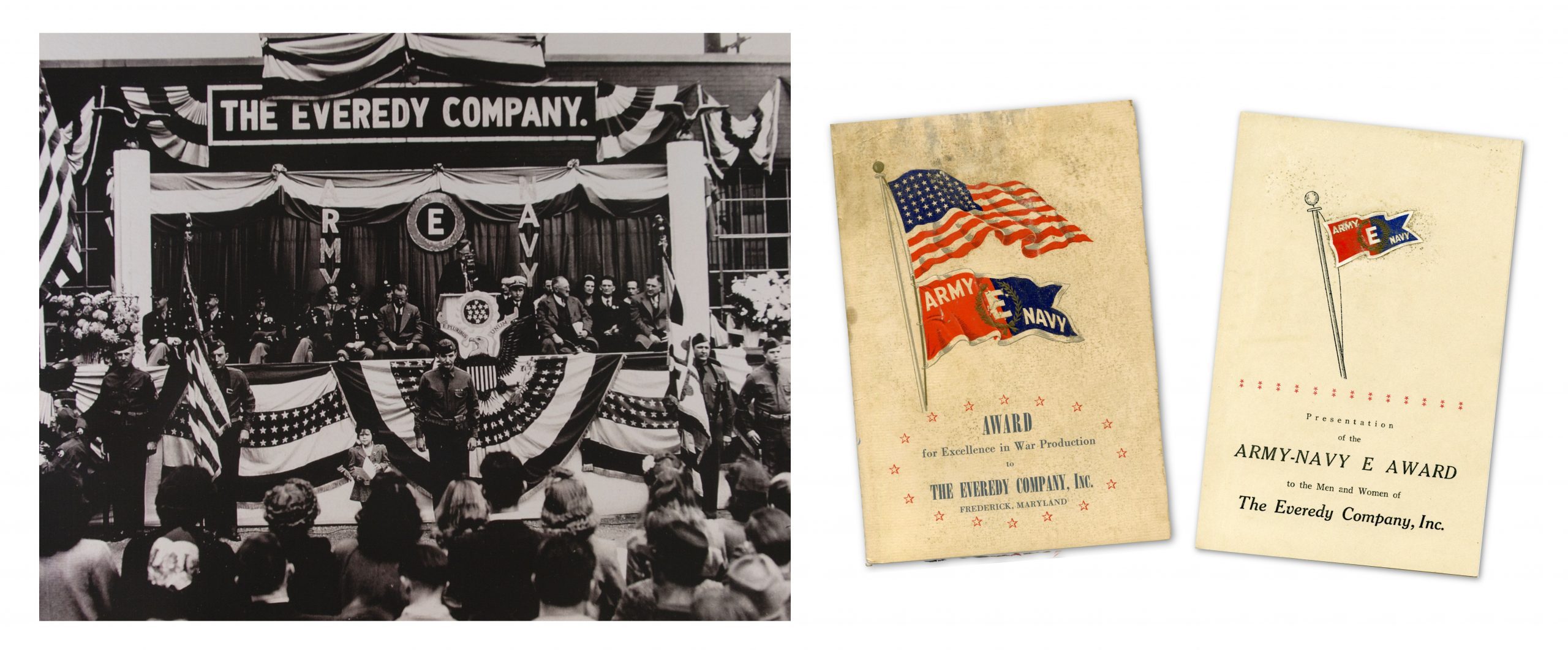

Perhaps one industrial company singularly defines the evolution of the County – Everedy Company. During prohibition (bottle capper), war (military supplies), and post-war (pots and pans for the home cook), the company invented and produced products for the economy of Frederick as it evolved over decades.

Two brothers, Harry and Robert Lebherz, incorporated the Everedy Company in Frederick on December 27, 1923. A third brother, William, joined the partnership two years later. They operated a manufacturing facility at the corner of East and East Church Streets, which opened during the Prohibition era. The Everedy Bottle Capper was the first of many products invented by Harry Lebherz, and homebrewers used it to cap or cork bottles of beer and wine. The company later produced can openers, mailboxes, screen door hardware, and other household items.

In the mid-1930s, Everedy introduced “Speedy Clean” chrome-plated cookware, which became a signature product and very popular with consumers. Everedy also was an early pioneer in the use of chrome plating in the automobile industry. Its products were distributed nationally and in Canada, Mexico, and South America. The Everedy Company competed against national cookware manufacturers, such as Farber and Revere, and prospered well into the 1970s. Carol Etchison, Marshall’s brother, joined Everedy in 1923 and retired on January 1, 1965 as a superintendent; one area of specialty for Carol was the chrome-plating science and application.

During World War II, Everedy produced spherical floats for anti-submarine nets, more than 200,000 land mines and two million grenades, and parts for rockets and bombs. The company developed folding fin stabilizers for rockets, reaching a production level of 10,000 per day, and created a machine that automatically folded bandages for the Red Cross. The average annual number of employees in peace time was 168 but rose to 435 at the peak of the war.

Standard International bought the company in 1958 and eventually operations transferred elsewhere; the company closed its doors in 1977. Now, the company’s site is a symbol of historic preservation and restoration as Everedy Square.

The C. Burr Artz Library

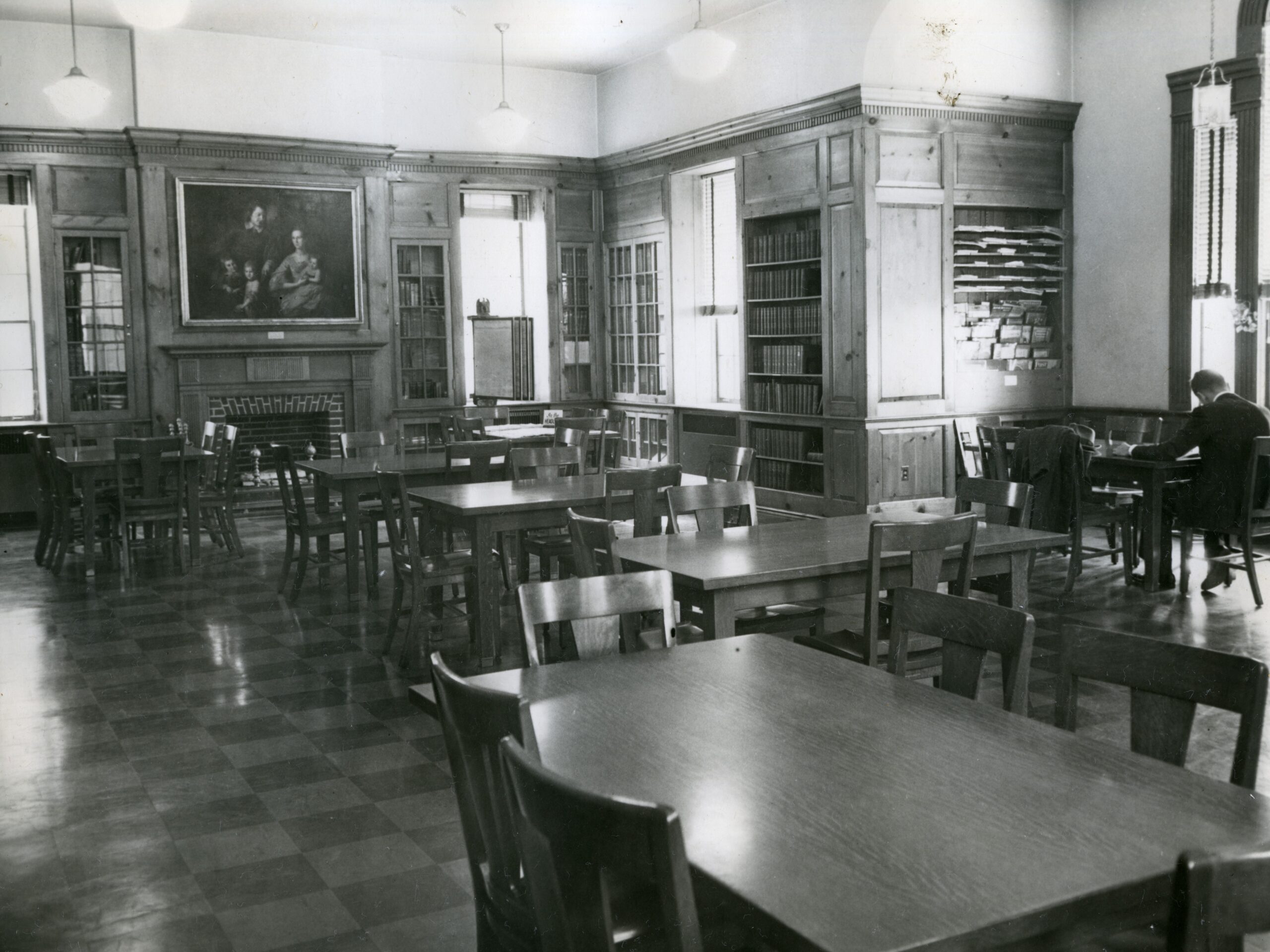

The first known attempt at a public library in Frederick occurred in 1865, after the Civil War ended, but it closed in 1870. The books transferred to the Maryland School for the Deaf, but the property it occupied – the Frederick Academy building, which was built in 1797 at Record and Council Streets – survived.

Oddly, the seeds of a permanent library in Frederick were planted in 1878, when Christian Burr Artz died in Chicago. Artz started his life in 1801 in Washington County but his family moved west to Illinois when he was young; it’s not clear when or why he returned to Frederick, but he met Margaret Thomas in the city and married her in 1845. The couple lived for a time on a 24-acre farm opposite Rose Hill Manor, which they bought in 1849. Artz was associated with the city’s nascent water company and served as a tax assessor for the government.

Artz moved his family west to Illinois in 1867. He bought tracts of land as well as houses in and around Chicago and northern Illinois, which over time became valuable because of railroad construction and city expansion. Upon his death, he left a large estate to his wife. When Margaret died in 1887, she left an estate that had grown even larger. Her only heir was the couple’s daughter, Victorine, who never married or had children. Margaret’s will provided support for her daughter but retained much of the estate and directed that at her daughter’s death, the estate be transferred to a trust overseen by three Frederick men who were charged with using the estate assets to fund and create a library in the city named for C Burr Artz. So, it became a gift for which Frederick would wait 44 years.

The Civic Club of Frederick learned about the library trust after Margaret’s death and began planning for and raising money toward a new library. The initial Free Library opened in the YMCA in 1914 then moved to the first floor of the Academy building in 1916, where it remained for 20 years. Racial segregation existed in Frederick through the period, and Black community leaders opened the Young Men’s Colored Library on Ice Street in 1913, which remained open until 1932.

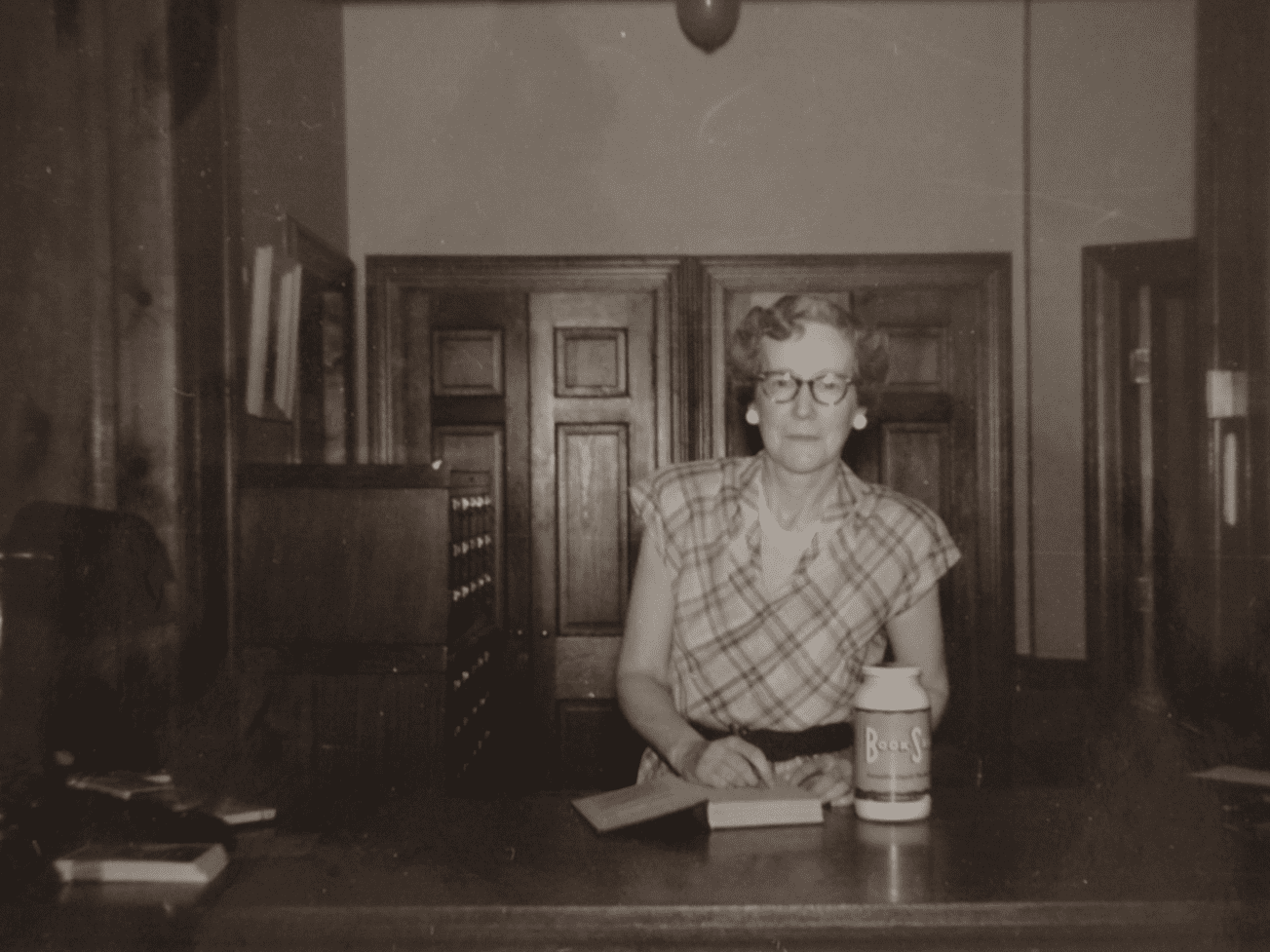

After Victorine died in 1931, trustees overseeing Margaret Artz’s estate allocated approximately $3 million (a 2023 valuation) to the new Frederick public library that would be named for her husband. The trustees also subsequently bought the Academy property and tore down the existing, decrepit building in 1936 to clear the site for a new structure. When the C Burr Artz library opened in 1938 on Record and Council Streets, Josephine Etchison, Marshall’s sister, became its first director, a position she held until her retirement in 1967. The Artz library began welcoming all Frederick readers in the 1950s.

Serving the Community

In the late 1800s, Frederick County was an enthusiastic adopter and supporter of fraternal organizations. In the main city as well as small towns across the county, lodges for Masons, Knights Templar, Odd Fellows, Knights of Pythias, and Red Men provided citizens and civic leaders with an institutional and social framework for community improvement. One common focus of the fraternal societies was promoting and often leading local change for the better, whatever that meant in the time. Another priority was extended care for its members as well as the widows and orphans who survived them, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when government services or programs typically did not exist for such needs. Widows and Orphans insurance, funded by member subscriptions, was a common by-product.

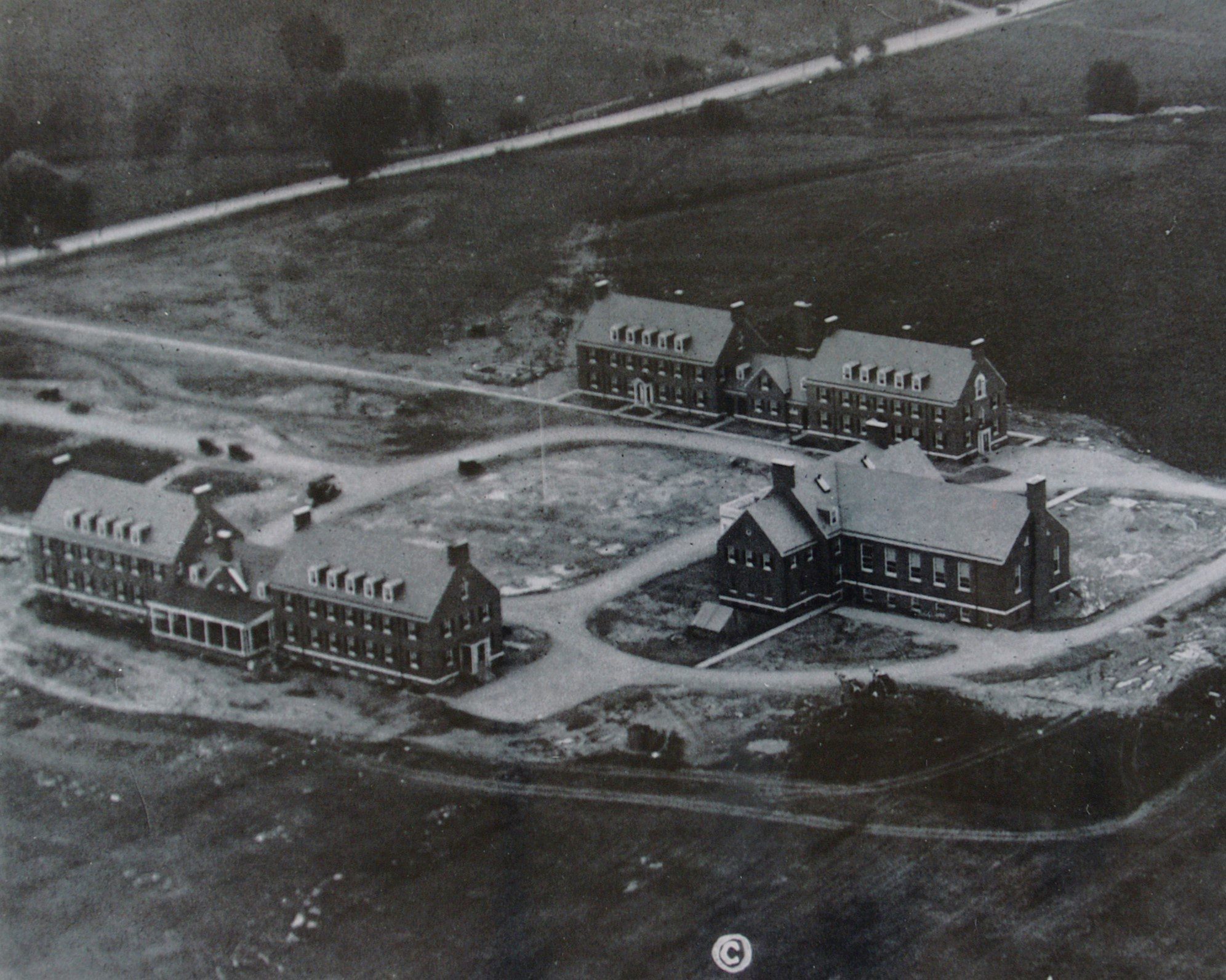

At the same time, another tradition existed in communities across America for “community” homes, sponsored by fraternal organizations, which served as living and care facilities for aged and indigent members as well as widows or orphans without other means of caring for themselves – the Independent Order of Odd Fellows was at the forefront of that movement. Frederick’s King David Lodge No. 50 organized in 1898 after an earlier lodge surrendered its charter, and Lodge No. 100 organized in 1908 to provide an additional membership outlet. The Odd Fellows mission advocated visiting the sick, relieving the distressed, burying the dead, and educating the orphans, and local lodges emphasized aid, assistance, and comfort for their members.

Maryland is the mother state of Odd Fellows in America – the England-based society formally organized in Baltimore in 1819 – but no community home existed in Maryland until 1925; 56 Odd Fellow homes existed elsewhere in the country by then. Planning for Frederick’s Odd Fellow’s Home began in June of 1921 following 117 consecutive nights of speeches delivered by Dorsey Etchison, Marshall’s uncle and the retiring grand master of the local Odd Fellows. Although his tenure leading the lodge was ending, Etchison remained fervently committed to promoting the facility and raising funds toward the purpose. The Maryland Odd Fellows lodges eventually raised nearly $500,000 to fund the effort, and Dorsey was known by his lodge and community peers as the driving force behind the project.

Construction crews laid the cornerstone in August 1923 and the IOOF took possession of the finished facility in February 1925; Governor Albert Ritchie spoke at its formal dedication ceremony in July of the same year. Dorsey Etchison also served on the committee that selected all the furnishings and equipment for the buildings. The original campus included three red-brick, Colonial Revival structures each topped by a slate roof, which were oriented in a cottage plan on land along North Market Street. The buildings, designed by Joseph Evans Sperry, served respectively as an orphanage, the community home, and the lodge. The lodge hosted member meetings but also commonly was the site for social and political events, dances, and musical performances. Frederick’s Odd Fellows Home closed in 2003 after nearly 80 years serving the community.

Building Community

Before the Civil War, roughly 5,000 free and 3,200 enslaved Black people lived and worked among one another in Frederick. In fact, free Blacks lived among Frederick’s White citizens, too. It would be misleading to say integration reflected every street, school, and church, but there were distinct Black neighborhoods and churches within the largely White community. Ironically, emancipation helped usher in a higher degree of segregation in Frederick as racial identities soon defined separate communities for Black and White on either side of Carroll Creek.

Henry Dorsey Etchison, Marshall’s uncle, passed the Maryland bar in 1898. It was common in the era that lawyers routinely represented clients in a host of court matters rather than specializing, and Dorsey was no different. News reports of his cases refer to real estate transfers, divorce, criminal charges as well as business disputes, and he earned a distinguished reputation as an advocate. His career also is notable for his willingness to represent Black defendants, which was made plain year after year in the news. Interestingly, one of Dorsey’s Black clients, William Grinage, would make a substantial and unique contribution to Frederick history and art.

Grinage was called both Mulatto and Black in census documents. Born in 1866, Grinage had a talent and passion for art. He supported himself and his family by working as a waiter, store clerk, and operating a photography studio. In 1914, Frederick’s court granted Grinage a divorce from his first wife, Sarah, and his attorney for that case was Dorsey Etchison. Grinage subsequently bought a house on All Saints Street and married a second time to Esther Wise. She was an educator who taught Black children in Frederick’s segregated public schools for three decades. William shared first place with Helen Smith for professional painters and drawers at the 1924 Great Frederick Fair. He also painted a portrait of Dorsey Etchison, which the subject liked so much, he advocated for Grinage to receive the commission to paint Francis Scott Key for the Kiwanis Club, which subsequently hung in the Francis Scott Key Hotel. It was his last painting before his death, and Grinage never saw it on display. He died in 1925.