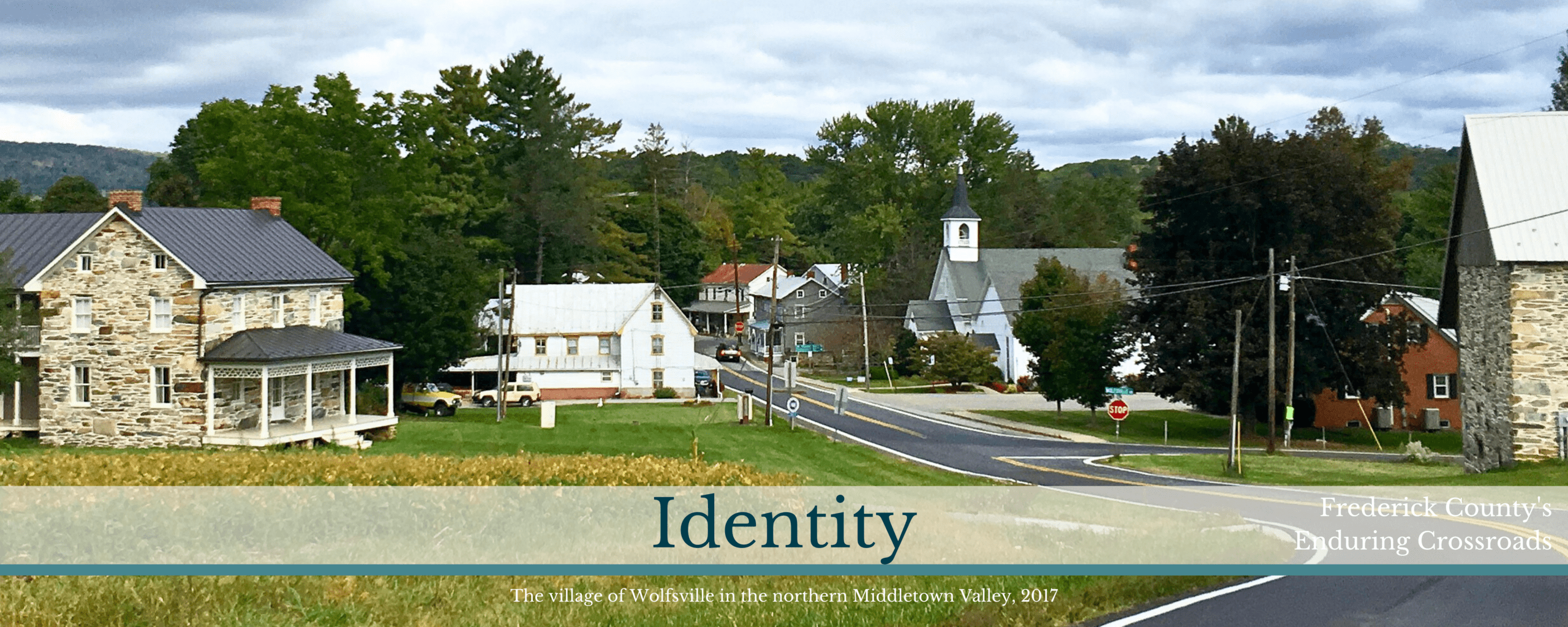

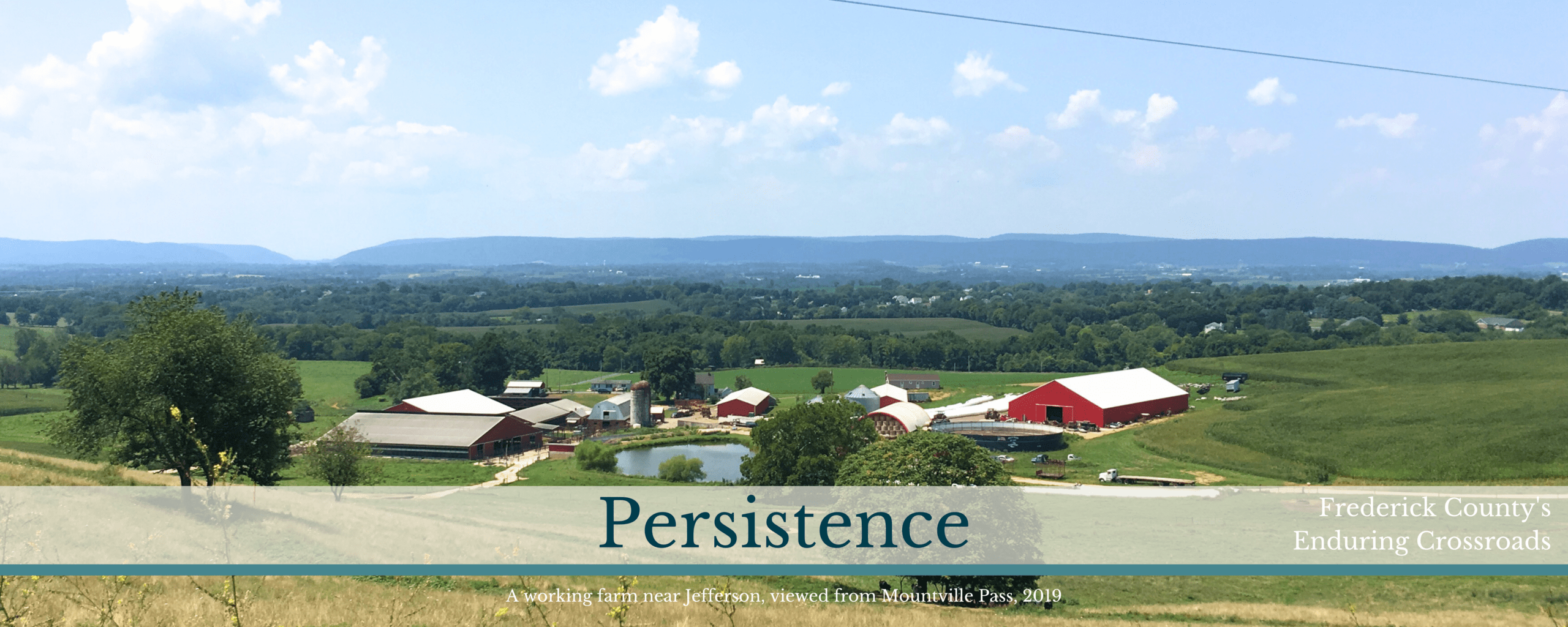

The history of Frederick County is written at its many crossroads, from rural villages and towns to the city’s Square Corner. Ancient paths of migration and trade established by indigenous peoples before European colonization endure as the threads that bind Frederick County’s oldest settlements. These crossroads have fostered technological innovation, witnessed significant moments in American history, and shaped communities that have persisted through three centuries of social, economic, and cultural transformation.

People of diverse backgrounds, ideas, and experiences converge at the crossroads of Frederick County. Main Streets are the stage for technological advances, civic action, and lively debate as people shape and reshape their communities to serve evolving needs. Rural villages have provided the commercial and industrial services necessary to Frederick County’s farmers. Towns welcome visitors from nearby metropolitan areas looking for rest and relaxation in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Maryland. In the 21st century, Frederick Countians turn to Main Streets as the foundation for a robust heritage tourism economy. Our crossroads remain a source of renewal for sustaining community across the centuries.

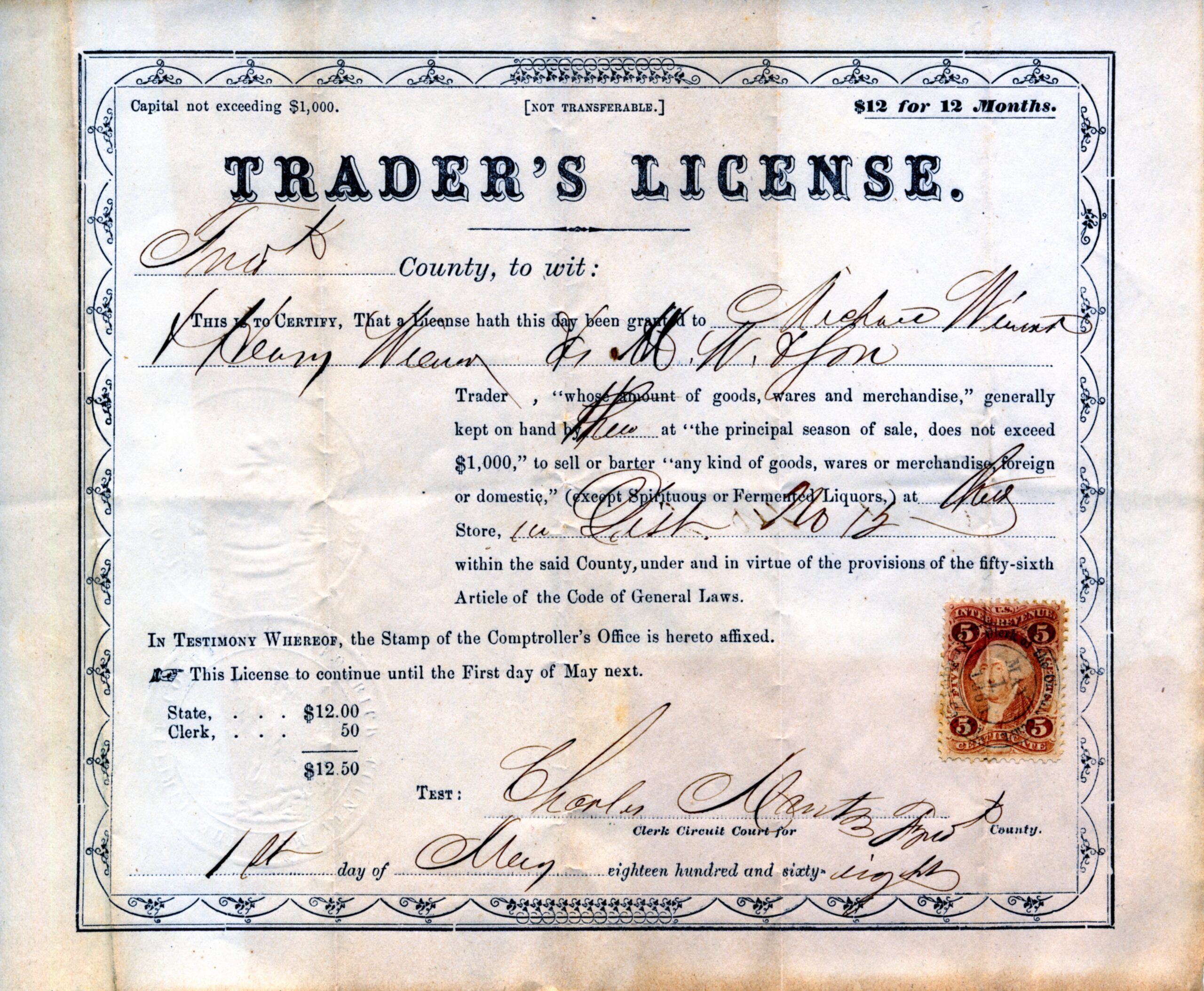

Before automobiles allowed for the concentration of business in larger towns, Frederick Countians turned to the Main Streets of small towns for their daily needs. These advertisements from Utica, Emmitsburg, and Jefferson display the types of businesses that thrived at Frederick County crossroads.

In the early-20th century, Frederick County’s crossroads were the scene of rapid technological innovation. This 1908 issue of The Valley Register of Middletown reported on the installation of electric lighting, a proposed trolley line connecting towns in the upper Middletown Valley, the growth of Brunswick City, and other exciting changes.

The communities built around Frederick County crossroads have worked together to overcome challenging circumstances. Faced with repeated outbreaks of typhoid from unsanitary water sources, Burkittsville residents installed a gravity-fed water system using these wooden pipes in 1913 to provide clean and reliable water to the community. (Loan from South Mountain Heritage Society)

The railroad transformed Frederick County’s crossroads and brought new technology that grew local businesses. This 1878 letter from John L. Roberts in Greenfield Mills to a customer in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, discusses how Adamstown, four miles from his mill, provided both railroad access and telegraph service.

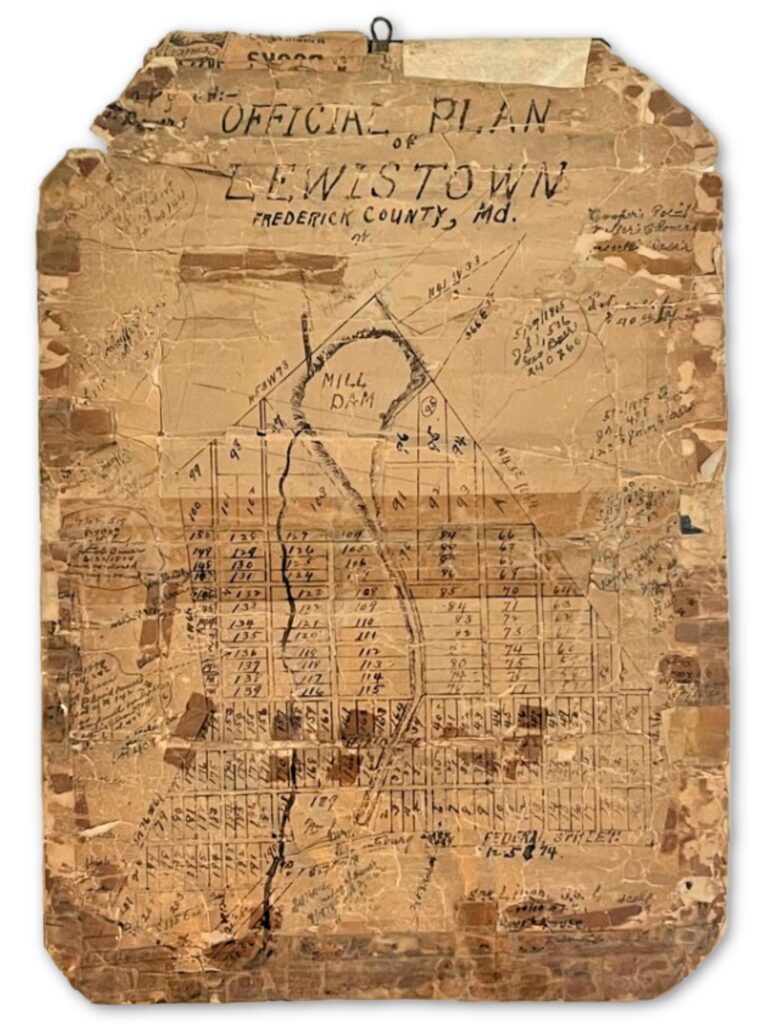

The growth of Frederick County crossroads has been influenced by local and national factors. When David Fundenburg laid out Lewistown in the early-19th century, he planned for a town that would grow around a pond and millrace for water-powered industry. When the railroad bypassed Lewistown, the town never grew to the extent shown in this plat.

The first public gas utility in the United States was started in Baltimore in 1816. By the mid-19th century, gas street lighting was a common example of technological innovation found on crossroads throughout Frederick County. This glass globe protected the flame of the gas street light that hung over the town square in Burkittsville. (Loan from South Mountain Heritage Society)

Frederick County’s history is tied to the land, its geography, and the resources derived from it. Plentiful timer and iron ore supported the building of iron furnaces in the county’s early history. Reliable sources of steady water powered mills and tanneries in many Frederick County towns. Quarries were excavated and kilns built to burn limestone for fertilizing fields and later paving roads. From the earliest days of the county’s history, fertile lands have made agriculture the chief industry. The harvests of fields and produce of livestock support canning and dairy plants. The survival of these farms, and the balance of protecting landscapes while accommodating growth, continues to reshape the character of Frederick County’s historic crossroads.

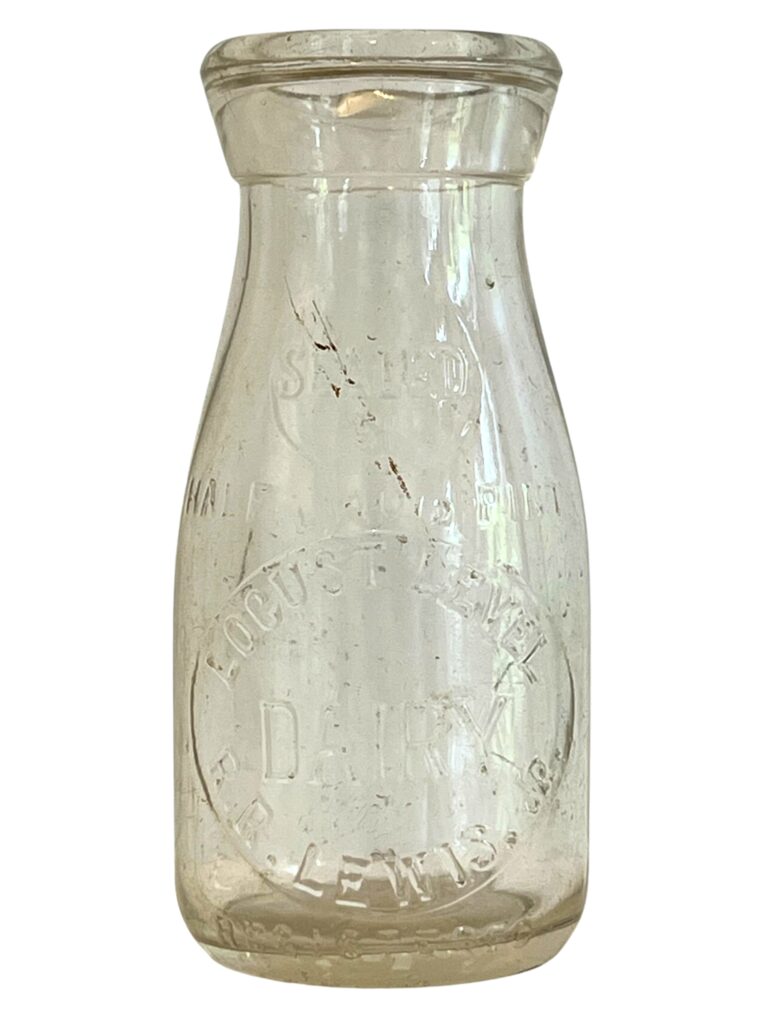

Dairy farming is one of the major sectors of Frederick County’s agricultural industry. In the 1880s, R. Rush Lewis, the owner of Locust Level Farm just south of Frederick, opened a large-scale dairy processing plant. Dairy plants across Frederick County sold their products in glass bottles like this one from Locust Level Farm.

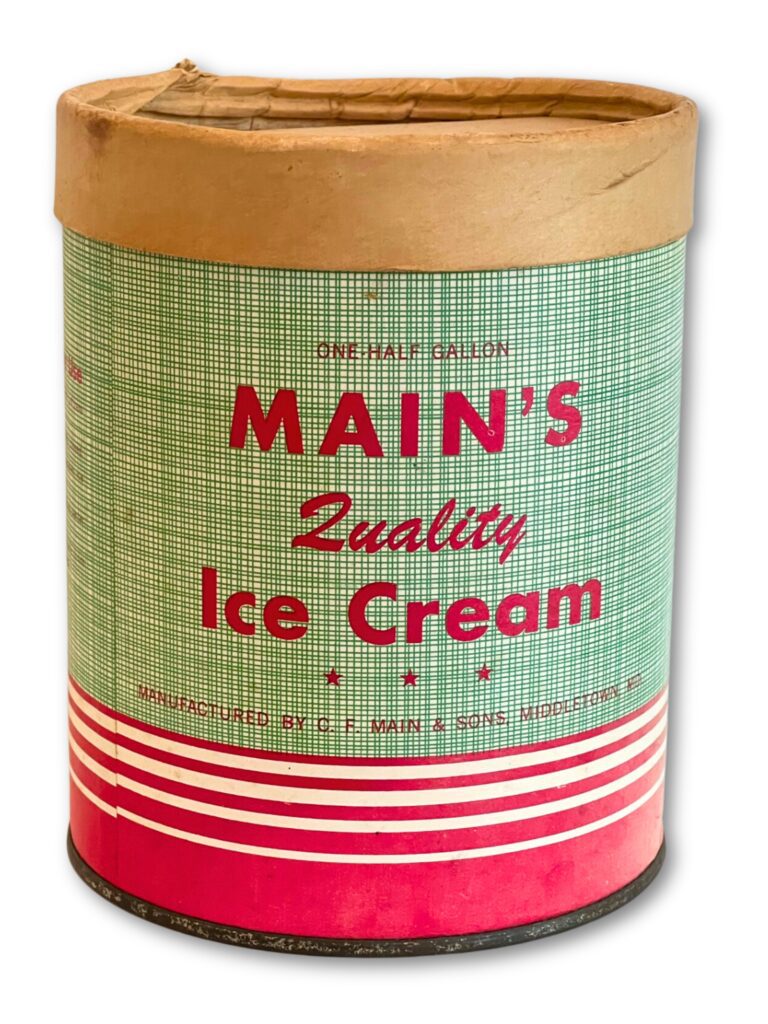

In 1922, Charles F. Main opened an ice cream factory on Main Street in Middletown which became a staple among local residents and visitors to Frederick County. The Middletown Valley’s vast dairy farms provided ample cream for producing Main’s Ice Cream, which remained in business until 1969.

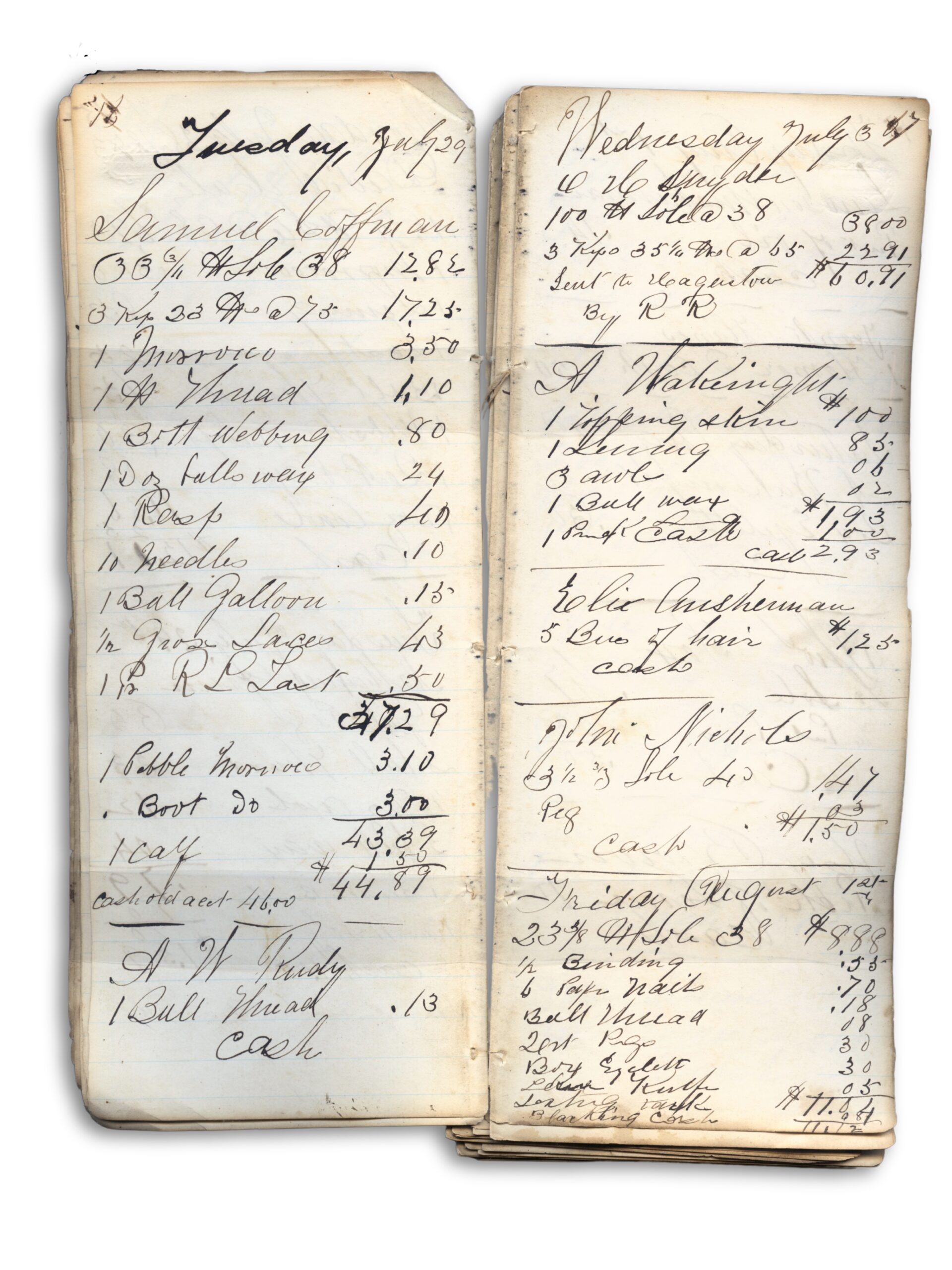

Most Frederick County crossroads had a tannery in the 19th century. Tanneries processed animal hides into leather products used in the home and on the farm. Bavarian immigrant Michael Weiner and his family operated Burkittsville’s tannery from 1846 until the early-20th century. This ledger from the tannery dates to the 1870s. (Loan from South Mountain Heritage Society)

Limestone has long been a source of industry for Frederick County. Once excavated, limestone can be burned to produce a powder substance called “quicklime,” a common fertilizer for farm fields. Woodsboro and Buckeystown were local centers for limestone quarries.

The LeGore Family built their first lime kiln in Woodsboro in 1861. The business grew rapidly to include a large quarry whose employees lived nearby in a company town. Limestone quarries continue to operate in Woodsboro, including S.W. Barrick and Sons, which has been in business since 1874.

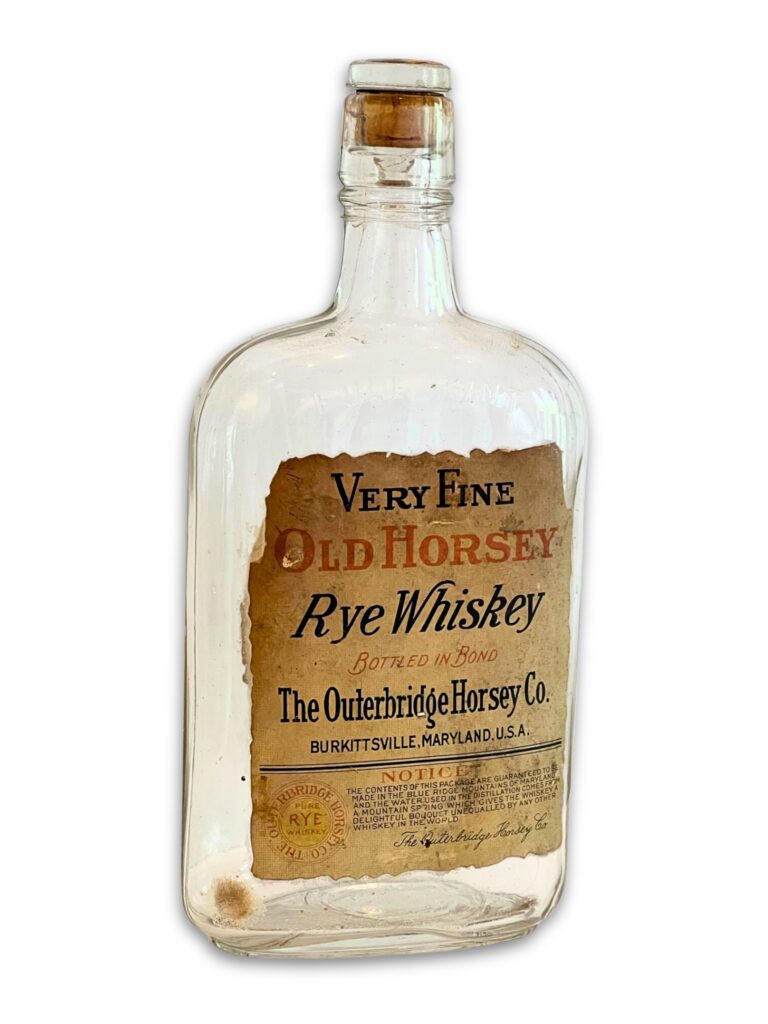

From the 1850s until the beginning of Prohibition, the Outerbridge Horsey Company produced one of Frederick County’s most popular brands of rye whiskey. Horsey credited the smooth flavor of his whiskey to the spring water he used from sources on South Mountain near the factory south of Burkittsville. (Loan from South Mountain Heritage Society)

William Besant and F. Columbus Knott maintained a business firm in Frederick distilling whiskey and operating a grocery business on West Patrick Street. They distilled whiskey from rye, a grain popular among Maryland farmers for its hardy nature and ability to grow in a range of soil types.

The resources of Frederick County’s land have also supported local artisans and craftspeople. From the 1850s until 1921, the Stottlemyer Family of Wolfsville produced furniture using wood turned from locally-harvested trees and seats caned from the bark. (Loan from Jody Brumage)

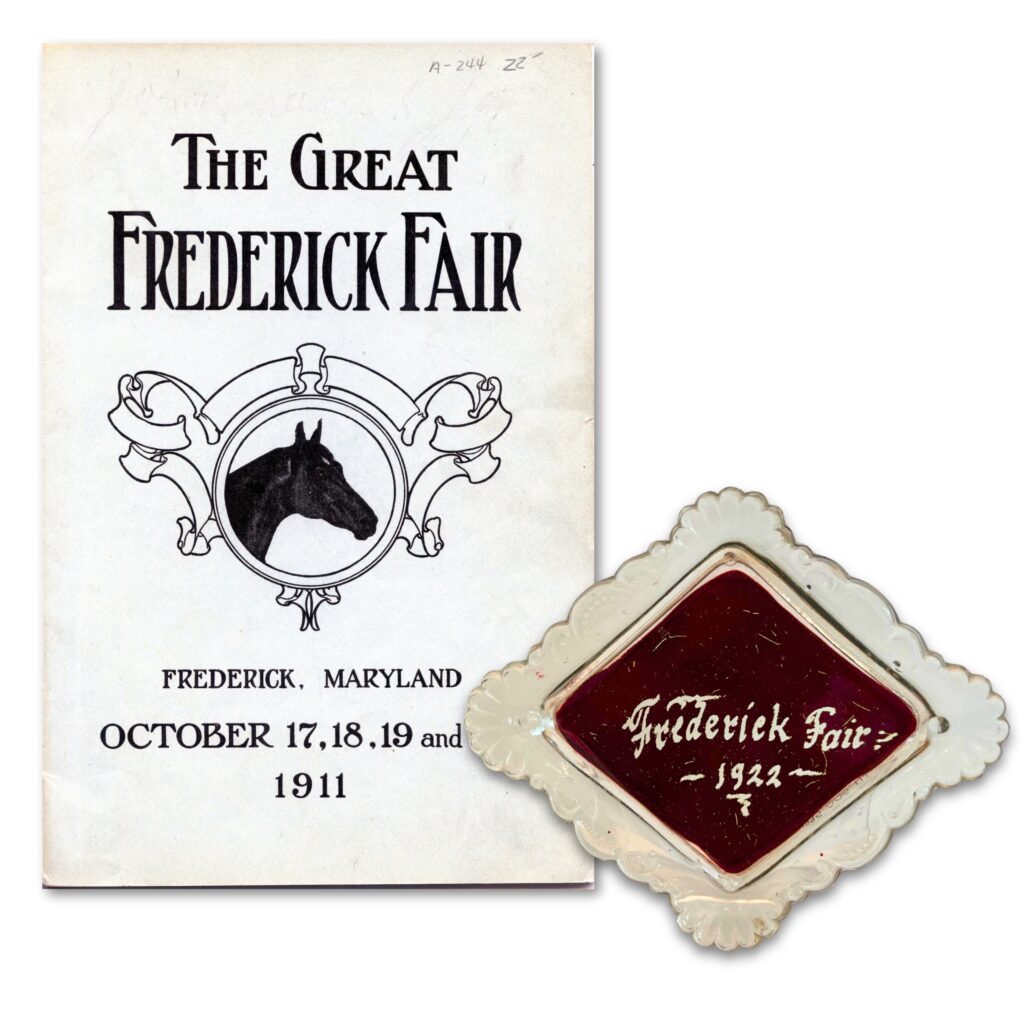

Beginning in 1853, the annual Great Frederick Fair brings families from across Frederick County and beyond to a celebration of the historic and present significance of agriculture to local communities. The fair provides the opportunity for education and entertainment, passing on an appreciation for farming to future generations.

Writers, artists, and storytellers gather at Frederick County crossroads to find inspiration and to craft an enduring rural identify for our communities. The Blue Ridge Mountains, quaint towns, and pastoral settings have inspired painters to capture Frederick County’s rural landscape. Authors have likewise found inspiration in the landscape and the people who inhabit it to craft stories and poetry that evoke the rural character of our communities and their role in national history. Collectively, their stories and their art continue to inspire an appreciation for the rural roots of Frederick County.

Artists have been active in capturing Frederick County landmarks for centuries. This two-hundred-year-old watercolor by George Schley, grandson of Frederick’s first settlers John Thomas and Catherine Schley, depicts the City Tavern on corner of West Patrick and North Court Streets, a landmark to early travelers heading west on the National Pike.

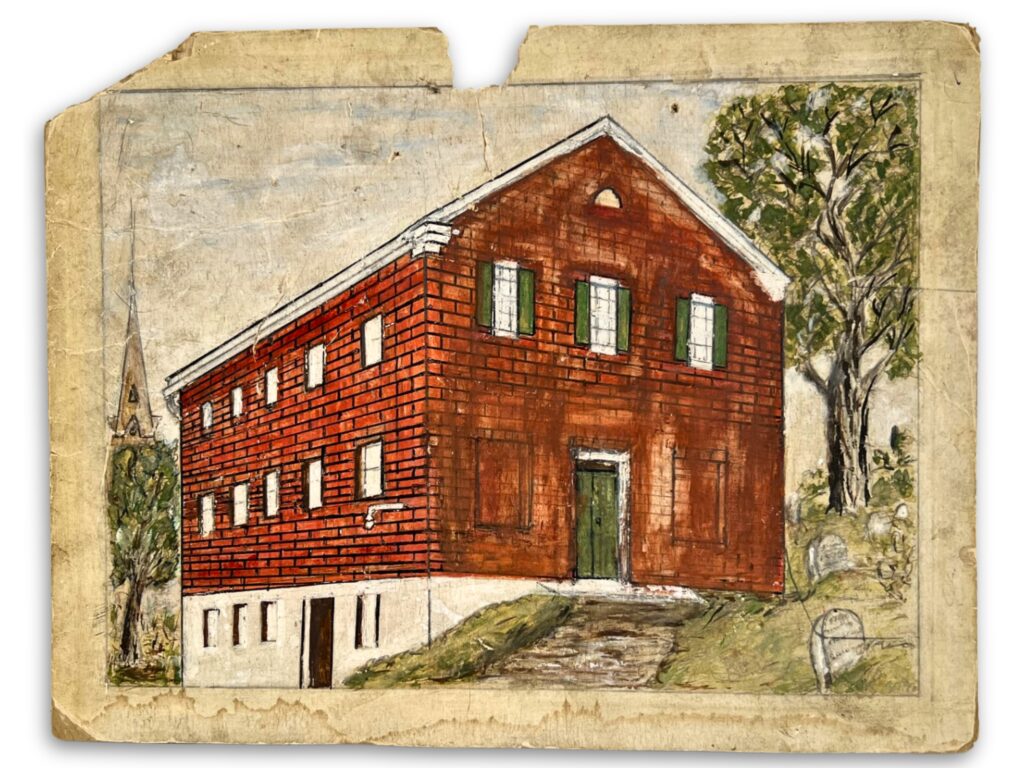

Artists capture landmarks around Frederick County crossroads that have disappeared from the landscape. An unnamed artist drew this gouache rendering of the “Old Hill Church,” the first building used by the Black congregation of Frederick’s historic Asbury United Methodist Church. The building was torn down after the present Asbury Church was built in 1921.

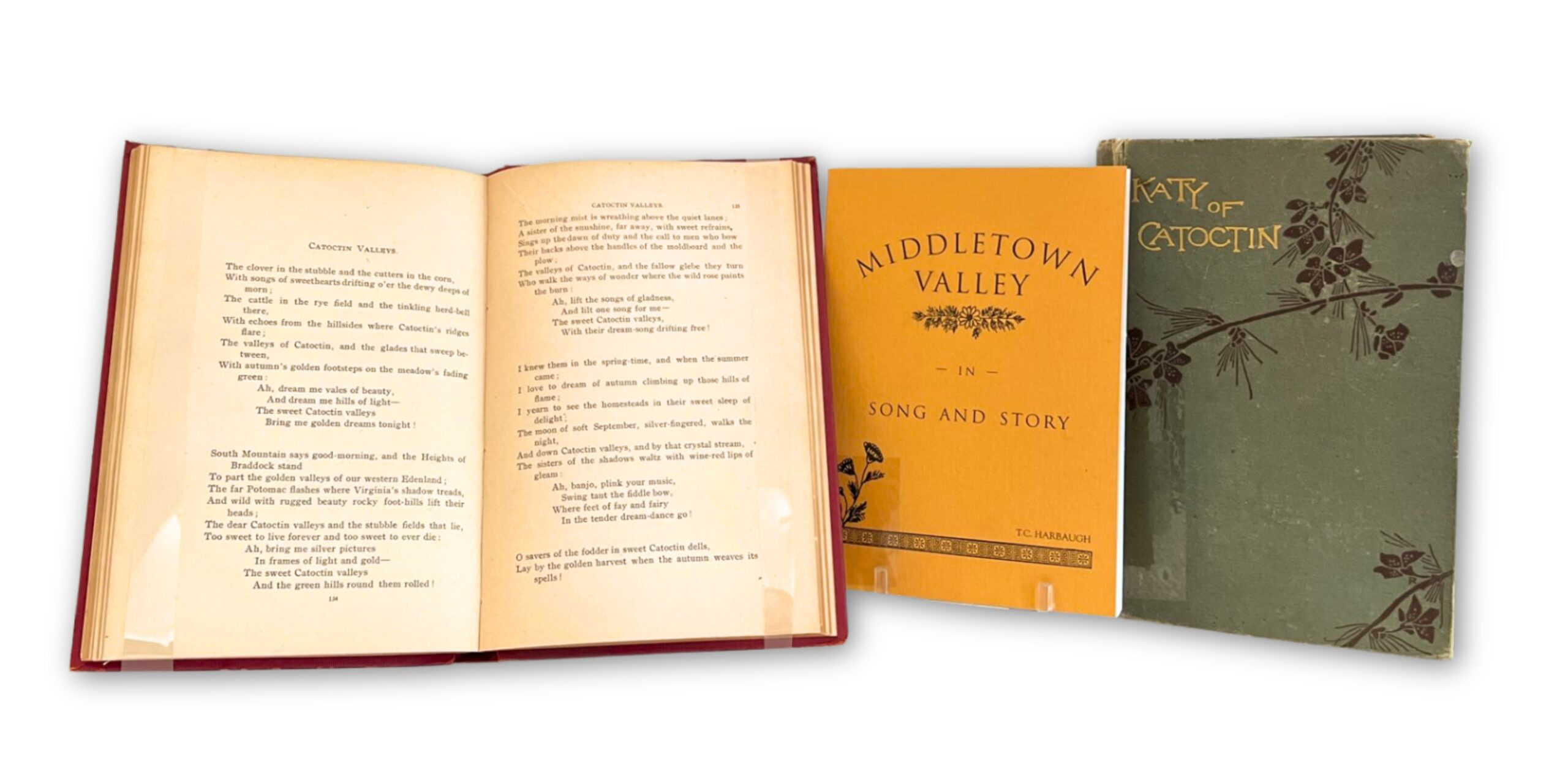

Works of literature pertaining to Frederick County’s rural and historic communities. (Left) Though not a Frederick native, Folger McKinsey’s penname “The Bentztown Bard,” was inspired by the neighborhood where he lived while editing the Frederick Daily News in the 1890s. McKinsey published poetry in this 1907 book and through his weekly column in The Baltimore Sun evoking Frederick County’s landscape, such as this poem entitled “Catoctin Valleys.” (Center) Middletown-born author Thomas C. Harbaugh lived much of his adult life in Ohio but wrote short stories and poems evoking the beauty and history of his hometown. Included in these short stories are folklore from the Revolutionary and Civil Wars and descriptions of long-lost landmarks on the Middletown Valley landscape. (Right) Frederick County’s position as a major crossroads of the American Civil War provided the backdrop for George Alfred Townsend’s 1886 historical romance Katy of Catoctin. While writing the novel, he became entranced with the area’s landscape and established a summer residence called “Gapland” on South Mountain near Burkittsville.

For over a century, the beauty of the Middletown Valley has lured artists and painters to capture the rural character of Frederick County. Baltimore artist Charles H. Walther made Middletown a destination for plein air painters in the 1920s and 30s when he brought students to paint the rural landscape. That legacy is carried on in this oil painting of Middletown by local artist Florene Ritchie. (Loan from Jody Brumage)

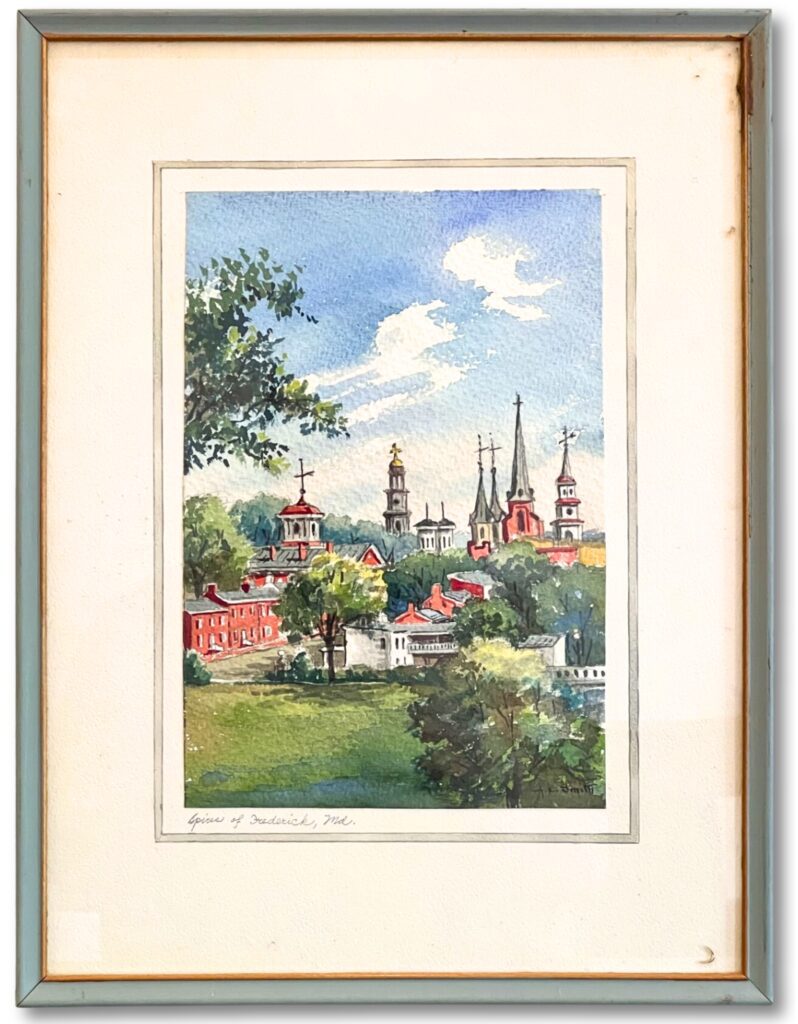

John Greenleaf Whittier immortalized Frederick’s historic Clustered Spires in his famous Ballad of Barbara Fritchie. They remain an indelible image of Frederick’s history and have been the subject of countless works of art, such as this watercolor by Frederick artist Helen L. Smith. A founder of Frederick’s vibrant art community, Smith ran her own studio and art store for over eighty years. (Loan from Jody Brumage)

Crossroads bring people together to collaborate in the face of adversity. In the era of segregation, vibrant Black communities grew around Frederick County where learning, spirituality, professional development, and expression were nurtured. Rural Women’s Clubs organized to offer women opportunities for education and socializing while also passing on traditional skills to future generations. LGBTQ+ people gather on Frederick County’s Main Streets to celebrate progress while rallying together for greater equality. Natural disasters and the pressures of growth and change bring people to Frederick County’s crossroads to seek means of adapting while striving to maintain a historical identity.

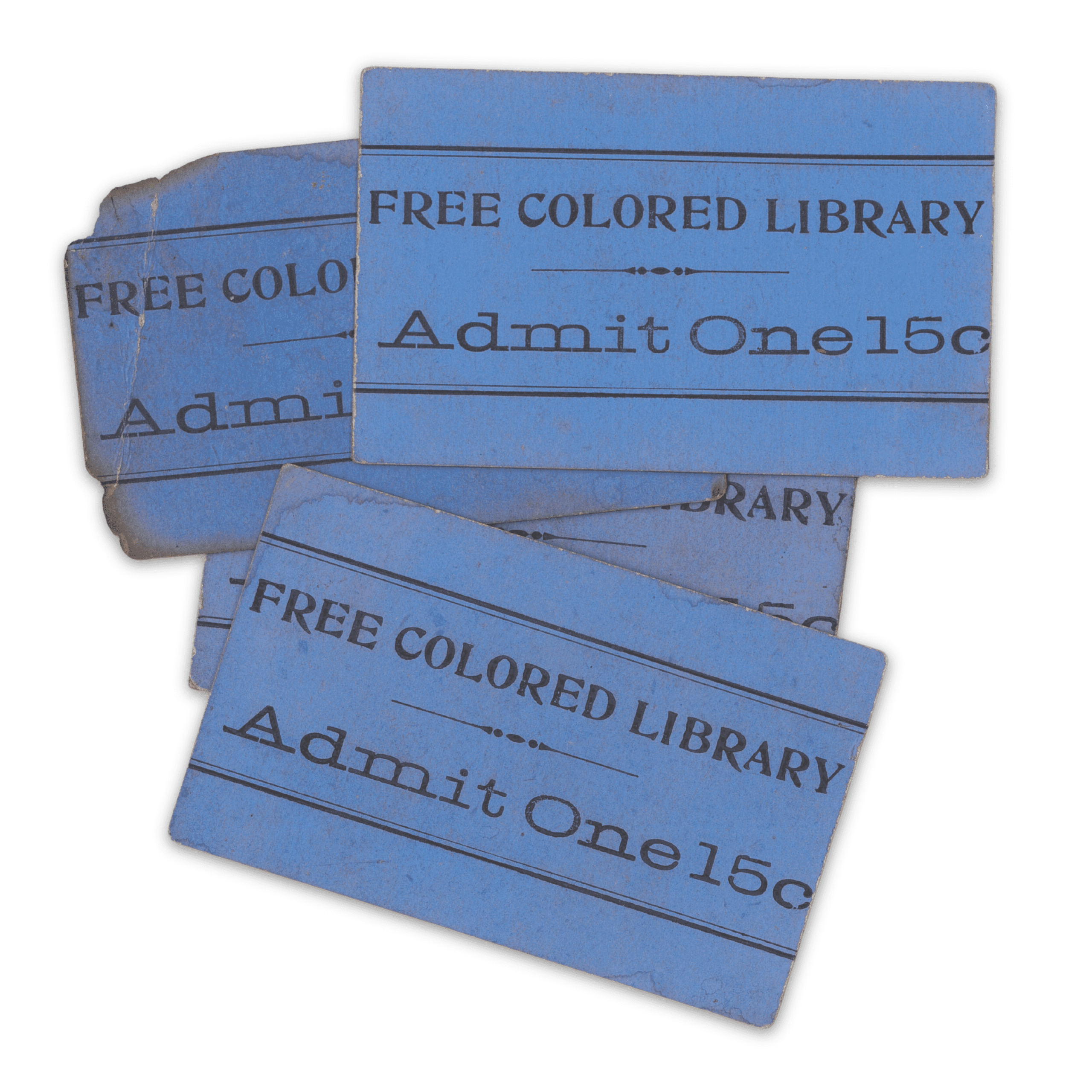

Crossroads communities are places of learning for all generations. Clifford Holland and other citizens of Frederick garnered public support for the creation of a library on Ice Street in 1913. The Free Colored Men’s Library provided access to information and learning for Black residents of Frederick until 1932.

For over 35 years, Esther Grinage taught Black children in Frederick’s segregated schools. An advocate for early education, the first kindergarten for Black children was named in her honor when it opened in 1937 on West All Saints Street. A scholarship for students studying to become teachers continues to carry on Esther’s legacy.

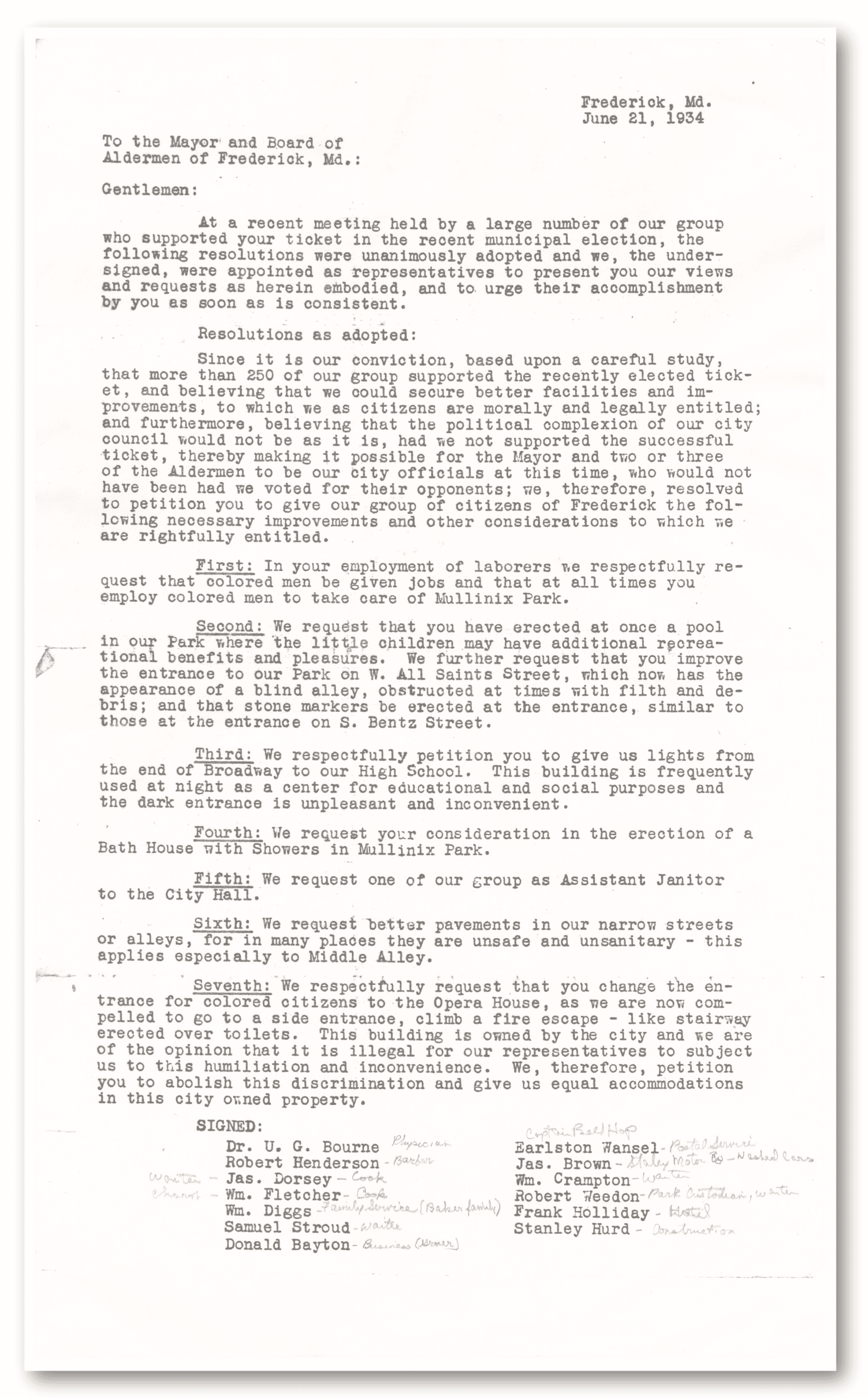

Racial discrimination in services and public amenities have historically hindered community development and equality. In 1934, Black citizens of Frederick’s All Saints Street neighborhood submitted this petition to the city’s mayor and board of alderman outlining the disparity between public facilities for white and Black residents.

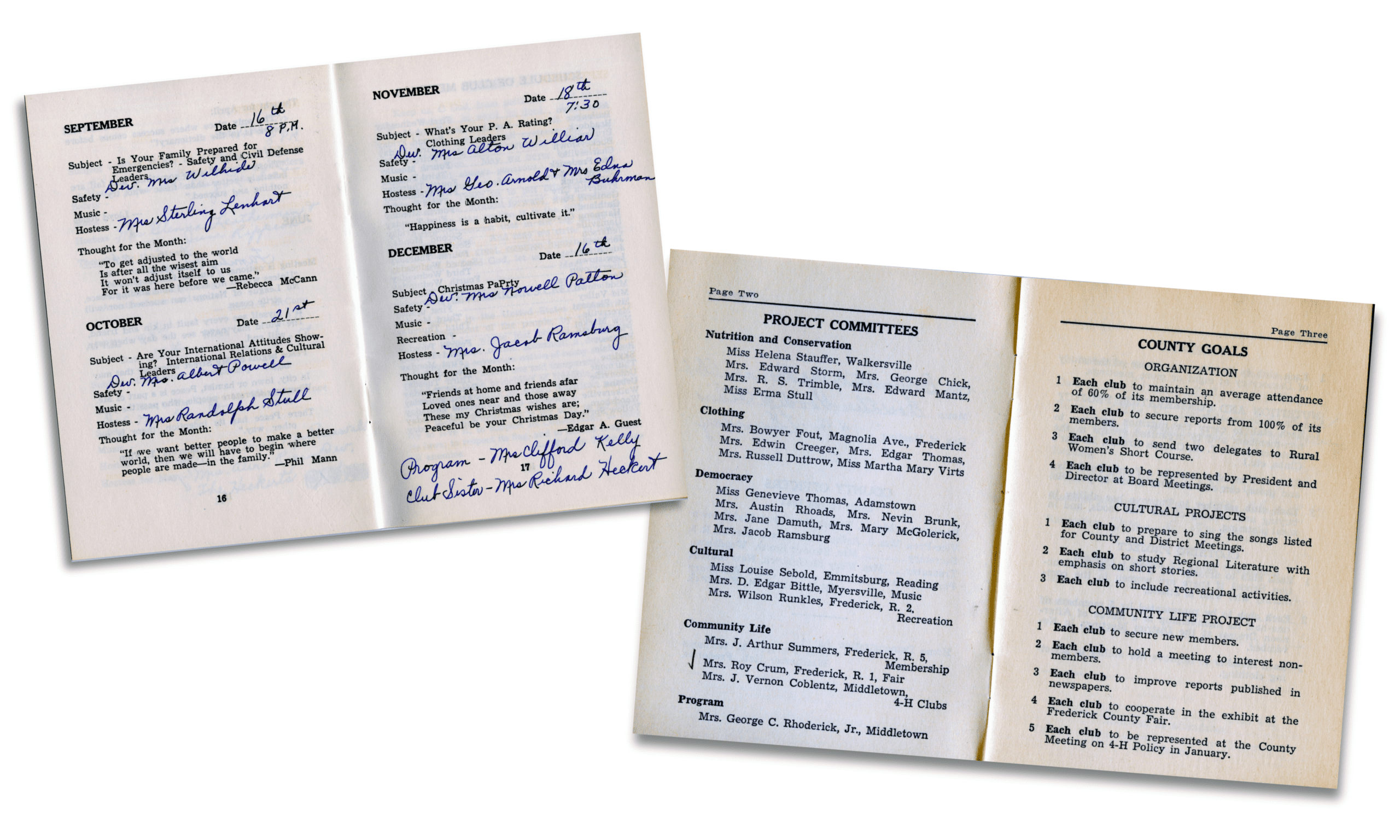

When women were excluded from the places where men gathered to socialize and exchange ideas, they formed their own organizations for this purpose. The Rural Women’s Club, later known as Homemakers Clubs, provided spaces for women to share their experiences, teach and learn from each other, and discuss important issues of the day.

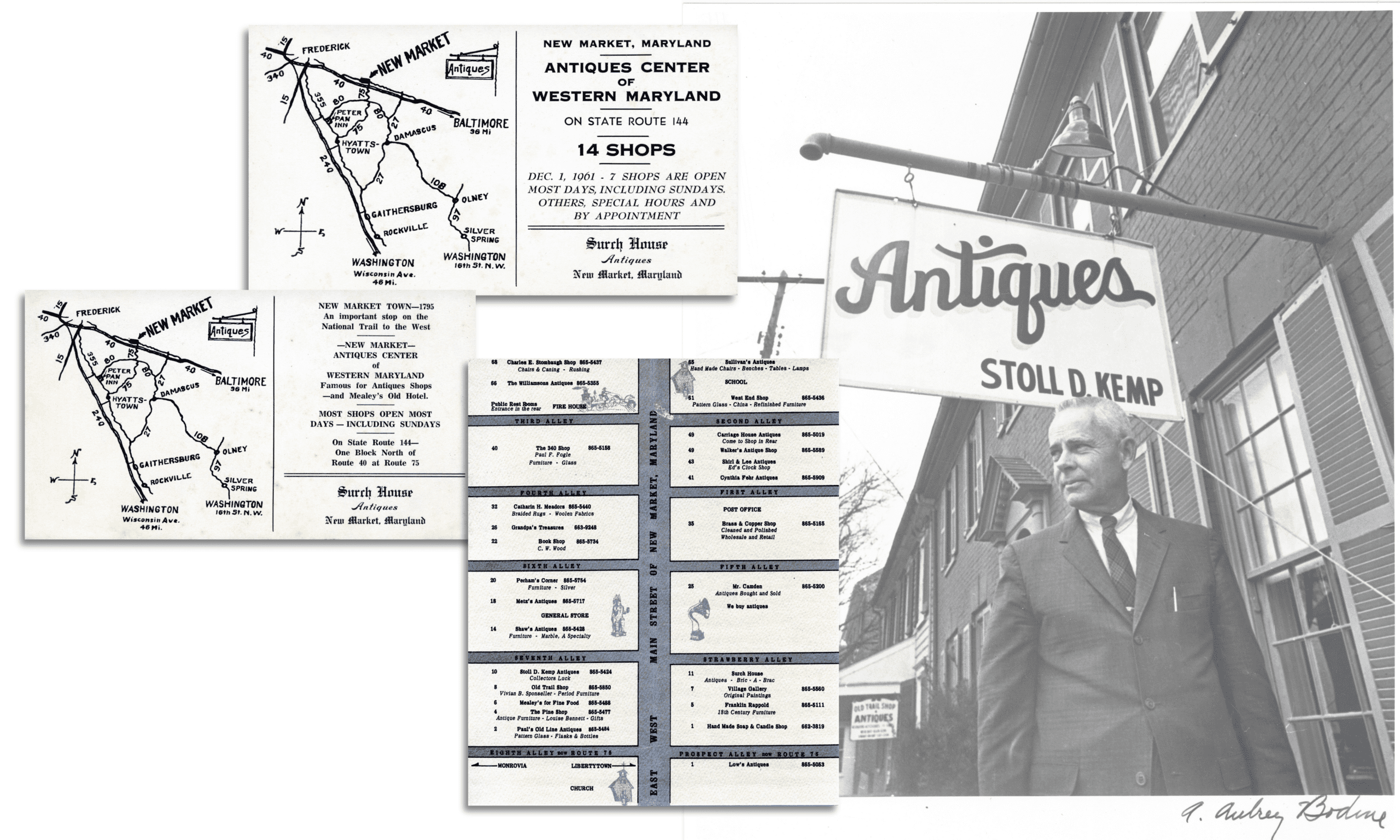

Seeing an opportunity to garner attention to the history of New Market, Stoll Kemp opened an antique store in 1938, soon to be followed by dozens of others. Branded as “the Antiques Capital of Maryland,” New Market became a destination and gained the resources to preserve its historic Main Street along the old National Pike. The portrait of Stoll Kemp was taken by noted Baltimore photographer A. Aubrey Bodine.

On October 9, 1976, downtown Frederick sustained significant damage when torrential rain storms caused Carroll Creek to overflow its banks. City officials and citizens rallied in an effort to save the historic downtown from ruin. Almost fifty years later, Frederick’s downtown has become a regional center of heritage tourism and preservation.

Frederick County’s Enduring Crossroads was opened in March 2023 as a complimentary exhibition to the Smithsonian Institution traveling display Crossroads: Change in Rural America which was hosted by Rose Hill Manor Park and Museum in Frederick from March 3 until April 14, 2023.