The transformation of wool production from home-based work by women to mechanized mills during the 19th century was a gradual one, involving not only new technologies but displacement of traditional norms in our society’s notion of work.

Mass-produced textiles emerged with the Revolutionary War, when there was an urgent and continuous need for thousands of uniforms and blankets. After the war and during the early 1800s, entrepreneurs built mills along waterways but they remained small producers, with a handful of workers serving the needs of the local population. There were large, regional producers in New England, but widespread, organized industry didn’t arise until after the Civil War.

The first textile mills replaced “fulling,” the final step in processing wool, which involved washing and beating or agitating woven wool cloth to produce a finer and more uniform fabric. Human power was no match for equipment that resembled an enormous, wooden washing machine powered by a water wheel.

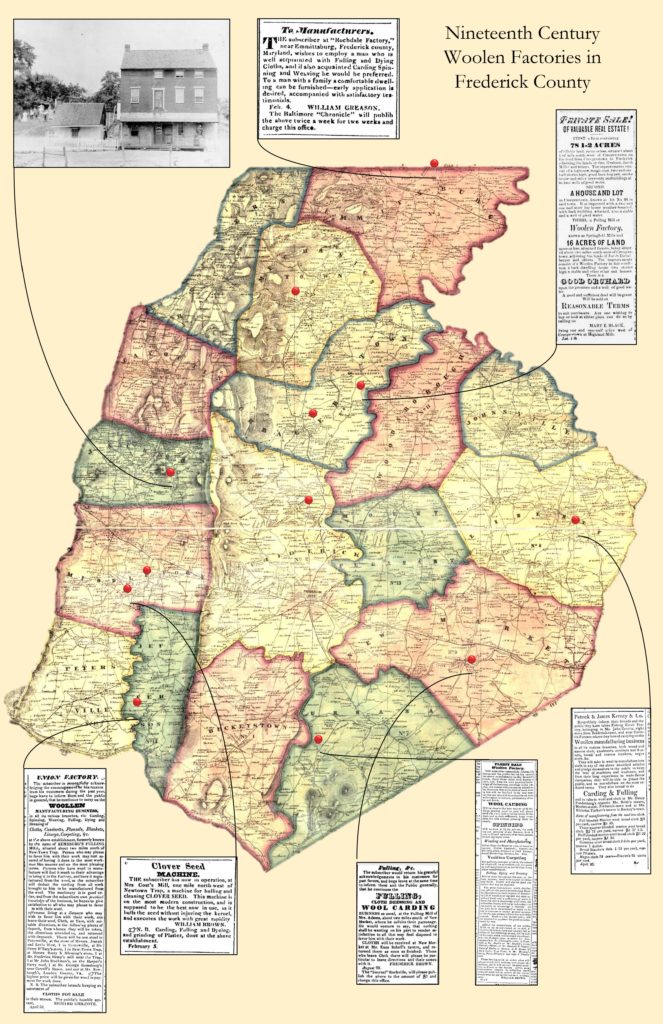

The second task to be mechanized was “carding.” Carding was a labor-intensive process for removing dirt and pulling fibers into alignment by the back-and-forth motion of two hand-held wood and wire paddles. Early carding machines replaced the paddles with a water-powered drum embedded with stiff wires. An early carding drum could process in twenty minutes the same amount of wool processed at home in a day. In 1811, there were 11 fulling mills and nine carding mills in Frederick County.

Not long after, woolen mills – manufacturing facilities that essentially mechanized the entire process of wool cloth production – were advertising their services. Initially, these mills performed custom work: a farmer dropped off home-harvested wool at a mill and came back later to collect finished cloth. These technological improvements enabled one miller, usually working with a few male family members, to accomplish the work previously done by many women in their homes.

As populations grew and clustered – creating centralized marketplaces – textile manufacturing expanded to meet demand. Local mills became obsolete reminders of the past. By 1870, there were only eight woolen mills in Frederick County, employing a total of 38 employees; two decades later Union Manufacturing Company in Frederick employed over 300 people.

The sewing machine, patented by Elias Howe in 1846, revolutionized the way clothes were made by replacing the hand-stitching of fabric with a machine. The machines operated by hand-turned wheel at first and later with a foot treadle, but electricity became the source of power in the 20th century. Whether it was used to sew quilts or clothes, the sewing machine reduced the time it took to do seamstry work. Its efficiency led to the transformation from textiles produced in the home to factories.

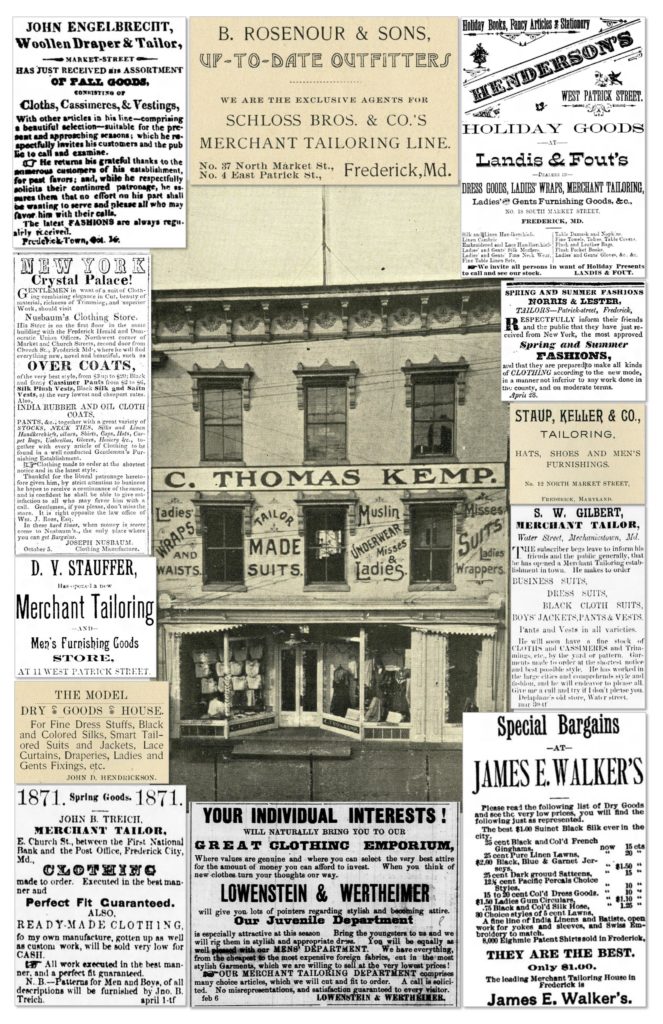

In early villages, water power created energy for small mills as well as artisans who used water-driven machines to forge tools. Living in a village differed dramatically from the farmstead experience. Individuals clustered closer together could exchange goods and services efficiently; a village with a general store, barrel maker, tool maker, potter, blacksmith, tanner, and tailor became a marketplace. People who moved off farmsteads often found jobs in these same stores and artisan shops.

The invention of machines enabled trained practitioners to produce goods easier and faster for their neighbors than an average person could do for him or herself. Sewing is an obvious example. Skilled artisans, acting as tailors within a village, usually produced garments more efficiently and of better quality than what most home-trained producers could accomplish. Likewise, income from jobs enabled consumers to buy finished goods rather than make them at home. Women continued sewing at home, but as their economic status improved they often sewed for their children but paid for custom dress-making for themselves.

Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht was a craftsman who lived and worked in a growing community. By 1818 at the age of 21, Engelbrecht already was working as a tailor. Later, in 1841, he joined his brothers Michael and William to operate a tailor’s shop on Market Street between Patrick and Church Streets. He also recorded the presence of other tailor shops, including Cromwell’s tailor shop at the corner of Patrick and Market Streets and another run by David Knise on South Market Street.

After the Civil War, America slowly evolved from self-sufficient farmsteads to an economy driven by growing industries, including oil, steel, lumber, electricity, mining, and garment manufacturing. Mechanization made farming less dependent on manual labor and also made factories more productive. Factory jobs offering reliable wages attracted workers in large numbers, and industrial centers became densely populated cities.

As significant as the changes were in the machinery that produced fabrics, the human labor sewing in factories was markedly different, too. The population in the country doubled between the Civil War’s end and the end of the century; much of the growth concentrated in the industrializing regions in the Northeast and upper Midwest. Substantial numbers of Black residents left southern states for northern urban areas and jobs, and European immigrants added to the labor force in cities.

The transition from producing textiles at home to factories was gradual but transformative. Yet, when women’s work – shearing, carding, fulling, spinning, and weaving – moved to factories, the women typically didn’t move with it. What was a part-time duty serving the family couldn’t be traded for a full-time job out of the house, because a woman’s other household tasks still needed attention. Ironically, female, young adults who formerly apprenticed under their mothers could accept jobs but social norms dictated that when a woman married, she left the factory – and paid work – to assume her role running a household.

In garment factories, men oversaw operations and assigned other men to the higher paying jobs of pattern makers and fabric cutters. Single women worked in lower-paying sewing jobs, earning wages by the number of items sewn and with no job security. Manufacturers also routinely contracted for sewing piecework outside the factories to immigrants and women who worked at home, creating competition that kept production quotas high and pay rates low. In the new industrialized textile economy, women were present but their role was diminished and depersonalized, and they no longer were in charge of their work.

The Garment Industry in Frederick County

The industrial revolution brought mechanization and mass production, which moved the production of clothing from the home to the factory. The technological and economic changes also contributed to new ideas about labor, especially for women, whose work had been limited almost entirely to the home.

Throughout the 19th century, as mechanization emerged and then industrialization transformed the economy, men left farms for factory jobs, but women largely were omitted from the workforce. They had a role at home, but they also were considered mentally and physically unable to perform the jobs or were deemed to be competing for jobs against their fathers and brothers – or future husbands. However, by the 1880s, women began showing up in factories to subsidize the family income during an era of rising costs of living.

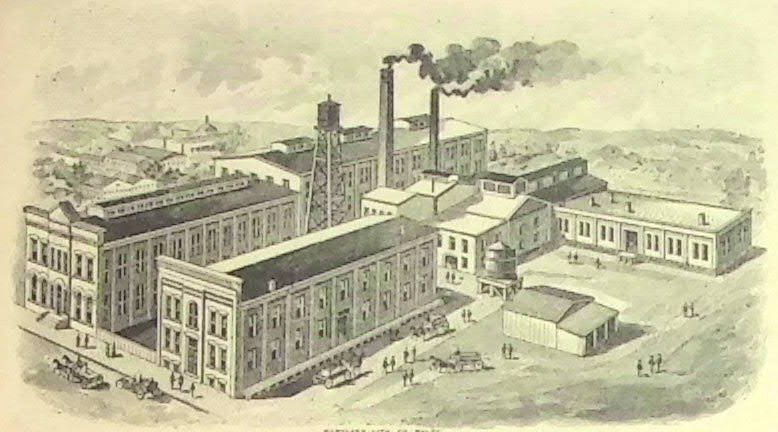

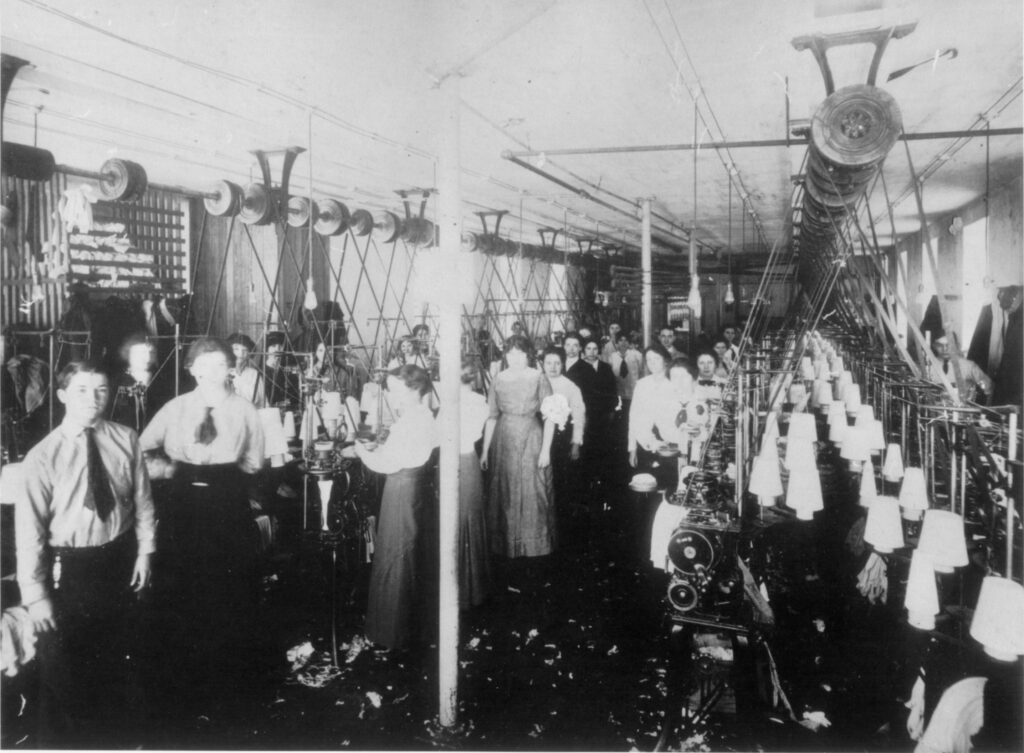

Five Frederick men embraced the push by women for factory jobs and collaborated as partners to create a company that would provide safe and respectable jobs for young women; they organized the Frederick Seamless Hosiery Company in 1887 with that goal. Within a few years, the company built a 35,000 square-foot factory along Carroll Creek on East Patrick Street to house machinery for producing hosiery for men, women, and children using cotton, silk, and wool. In 1889, the owners reincorporated the business as the Union Manufacturing Company.

At its peak, Union Manufacturing employed around 350 workers and opened branch factories in Emmitsburg and Thurmont.

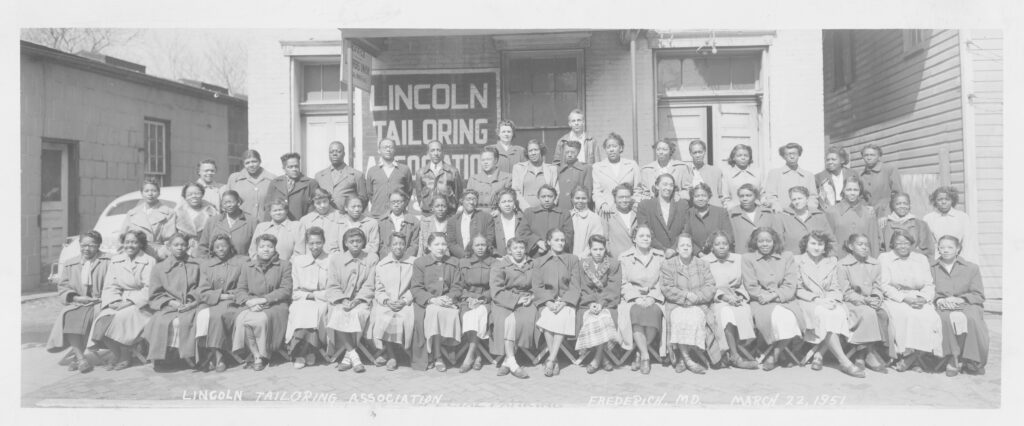

Baltimore businessman Abraham Sagner and his sons formed the Frederick Tailoring Company in 1933, which opened on East Fourth Street. The company produced formal and casual menswear. In 1945, the Lincoln Tailoring Association began operations on West All Saints Street, advertising “Opportunity for Colored Women” to receive forty-hour, five-day work weeks in a “clean, warm” factory with training and full pay upon hiring.