and the Attempt to Make a Resort on Lamb’s Knoll

Maryland’s section of the Blue Ridge Mountain Range defines the landscape of Frederick County and has been a significant factor in shaping its history. These ridges informed the paths of migration used by the earliest immigrant and colonial settlers to the county. They provided the raw materials that fueled the early industrial development of iron furnaces. During the Civil War, a significant battle was waged for control of three passes on South Mountain in the lead up to the Battle of Antietam. In the decades after the war, the mountains became the focus of a new industry: tourism.

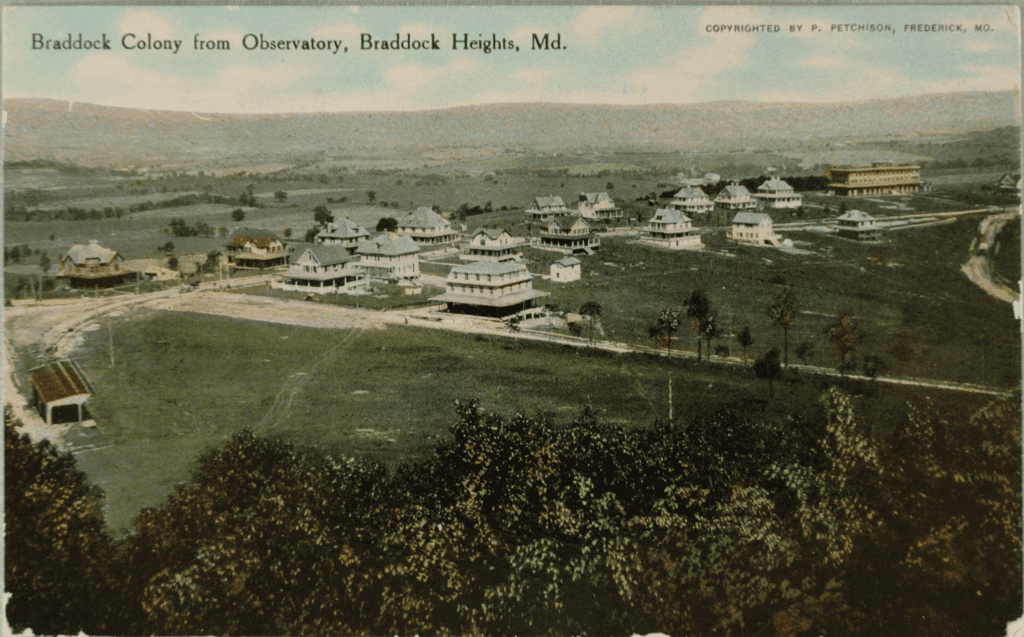

Entrepreneurs recognized the scenic beauty of Maryland’s Blue Ridge Mountains and their potential to be popular resort locations for families living in crowded cities like Baltimore and Washington, DC. In 1877, the Western Maryland Railroad developed Pen Mar Park on South Mountain. A similar development was started by George William Smith at Braddock Heights in 1894. The Black Rock Hotel at Wolfsville, the Valley View Manor on Catoctin Mountain, and dozens of boarding houses established in communities close to the mountains like Middletown, Sabillasville, and Thurmont catered to growing numbers of visitors seeking a quiet and cool refuge from crowded, bustling cities.

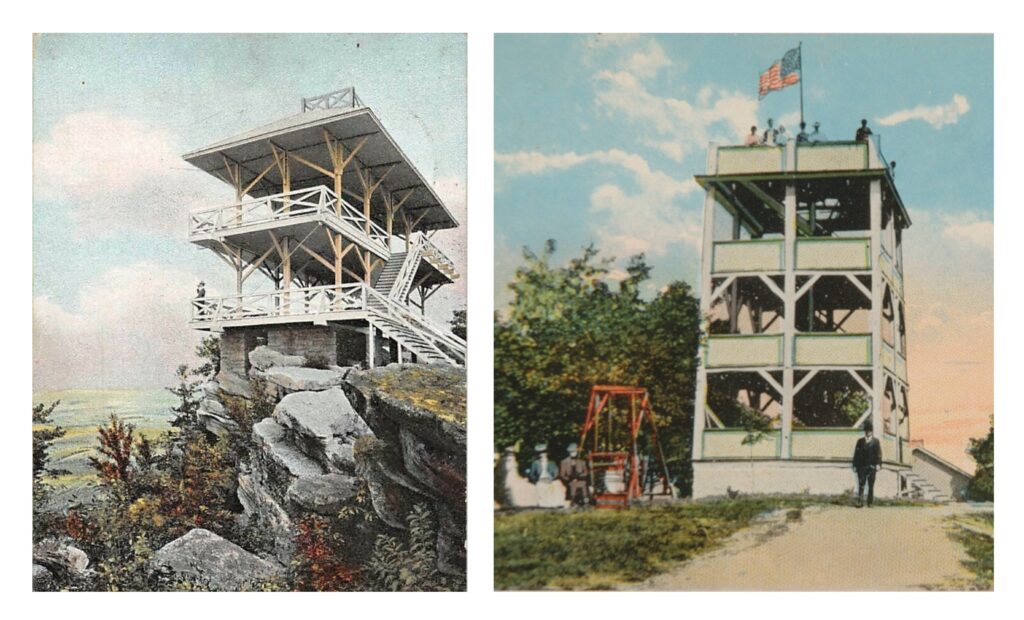

Amid the rapid development of resort spots in the Maryland Mountains, two farmers living in southwestern Frederick County attempted to create another. On September 13, 1895, Middletown’s Valley Register reported that John W. Wilson and Oliver Sigler were opening a two-story observation tower on Lamb’s Knoll. Rising to 1,758 feet above sea level, Lamb’s Knoll is the second highest peak of South Mountain during its course in Maryland (the tallest, Mount Quirauk, is located near the Mason Dixon Line at Pen Mar). The observatory was built on a fifty-seven acre tract which Wilson had purchased six years earlier from Dr. William Boteler.

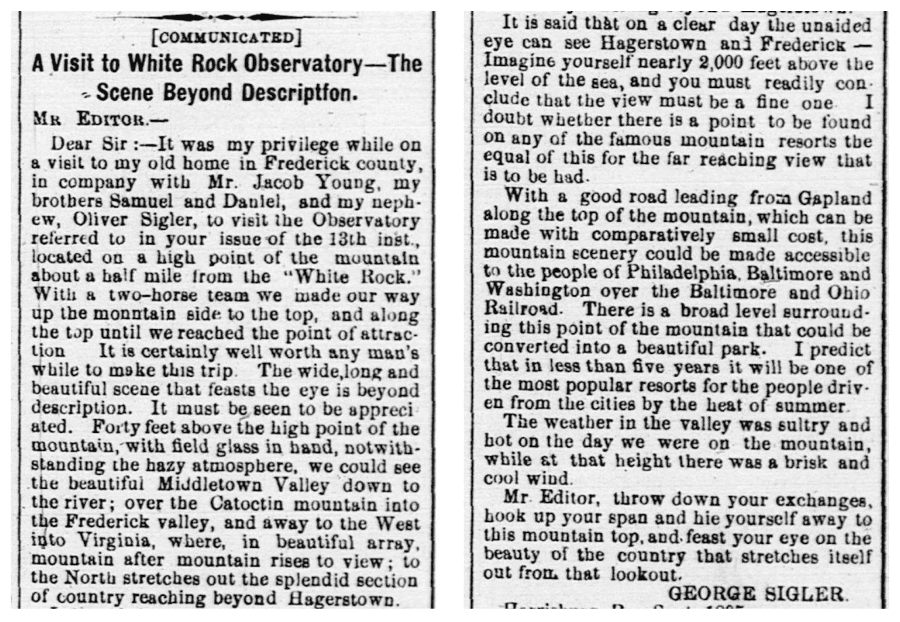

Local reporting on the new observatory speculated that it might become the central attraction of a new resort. One month after its completion, the Valley Register published a letter describing a visit to the observatory. The author, Rev. George Sigler, declared “It is certainly well worth any man’s while to make this trip. The wide, long, and beautiful scene that feasts the eye is beyond description.” The observatory had an uninterrupted panoramic view of four states and, according to Rev. Sigler, the unaided eye could easily see landmarks of the cities of Hagerstown and Frederick on a clear day. Rev. Sigler wrote that “there is a broad level surrounding this point of the mountain that could be converted into a beautiful park.”

Wilson and Sigler had reason to believe in the possibility of such a development around their observatory. One of the first attractions built at Pen Mar was the observatory built at High Rock on South Mountain. A similar attraction enjoyed enduring popularity at Braddock Heights. They also had an important ally who saw their investment as part of a grander plan for the development of South Mountain as an attraction.

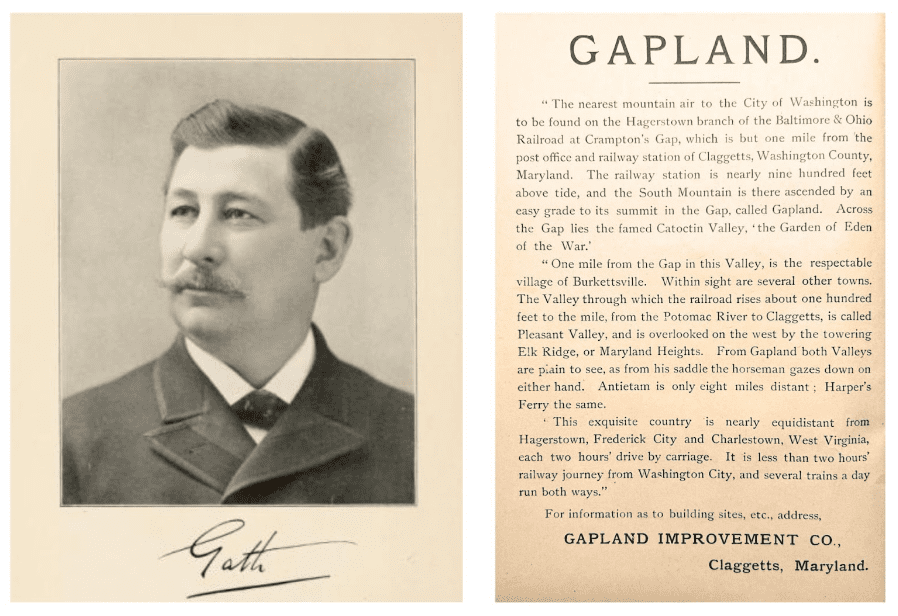

George Alfred Townsend, the popular journalist and author who built his mountaintop estate “Gapland” in Crampton’s Gap, had his own vision for making South Mountain a scenic and historical destination. Townsend formed a corporation that improved the road leading from Crampton’s Gap down to the nearby depot on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad’s Washington County Branch. He also formed the Gapland Improvement Company that advertised building lots to families in the cities looking for mountain land to establish vacation residences. However, Townsend realized improved roads to access the top of the mountain were necessary in order for South Mountain to flourish as a resort destination.

In an editorial that appeared in “The Valley Register” on October 18, 1895, the author (likely Townsend) wrote “the look-out just placed on Mount Panorama [Lamb’s Knoll], near the White Rock, South Mountain, suggests to me the importance of having the government in the present generation, which is alive to the subject of illustrating the Civil War, connect the three battle gaps on South Mountain by a road along the mountain’s nearly level ridge.” This road would have passed by Wilson and Sigler’s observatory on Lamb’s Knoll and made the site easily accessible.

However, no such road would ever be constructed, and without it, the observatory on Lamb’s Knoll remained accessible only by the several narrow, steep logging roads that climbed the mountain from the south, east, and north. The structure was nearly destroyed just two months after it was built when a wildfire swept over South Mountain in November 1895. The observatory was saved from this fire, but may have fallen victim to another blaze in 1910, by which time the dream of a resort on Lamb’s Knoll had ended. In 1933, the Civilian Conservation Corps erected an 80 foot fire tower near the site of the 1895 observatory. This tower became a popular viewing spot for many decades to a different type of recreational tourist: hikers passing over Lamb’s Knoll on the Appalachian Trail.

August 7, 2024 by Jody Brumage, Heritage Frederick Archivist